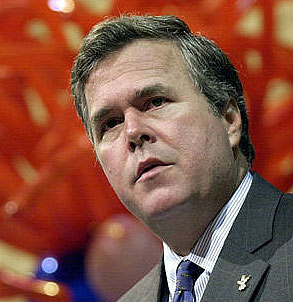

A U.S. Justice Department lawsuit against a former business partner of Florida Gov. Jeb Bush is raising new questions about yet another Bush’s old business dealings. State Democrats think the scrutiny could be their best chance to evict Bush from the governor’s office in November. As one Florida Democratic operative puts it, the key to erasing Bush’s double-digit lead over his potential Democratic challengers, former U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno and Tampa attorney Bill McBride, is to tell the story of how Bush “came to Miami with chickenshit, and turned it into chicken salad.”

Bush has endured a long, hot summer of hideous headlines — on everything from his daughter Noelle’s drug conviction to the ongoing scandal at the state’s social services agency. Department of Children and Families head Kathleen Kearney was forced to resign after 5-year-old Rilya Wilson disappeared from state custody, and the department had to admit there are many other children under its purview that it cannot find. An investigation by the South Florida Sun-Sentinel quickly turned up nine of the missing children the agency had lost track of. Trouble continued when Bush tapped Oklahoman Jerry Reiger to replace Kearney. Reiger’s name appears on a 1989 article titled “The Christian World View of the Family,” published by the Coalition on Revival, which condones spanking of children, even if it causes bruises or welts, and insists women should not work outside the home. Reiger, listed as the group’s co-chairman, now says he had nothing to do with the article.

So far, though, neither frontrunner Reno nor McBride, who will face off in a Sept. 10 primary for the right to challenge Bush, has been able to use the bad news to gain traction against Bush. A recent Florida television station poll showed Reno trailing Bush by 15 points. (The same poll shows Reno with a 55-22 lead over McBride.) Florida Democrats say they’ve been frustrated by the lack of national media attention to the governor’s business scandal. And they haven’t been able to convince national Democrats that the scandal, or any of Jeb Bush’s other political problems, justifies a major national investment of time and money in the Florida governor’s race. That could change, they insist, if this latest Bush business scandal develops legs.

Jeb Bush’s path to fortune and fame follows a familiar Bush family trajectory — use family connections to help make a quick killing in the private sector, and use that money and business experience to launch a political career. It’s a story that’s been well documented since the media began asking questions about President Bush’s past business deals with Harken Energy Corp. and the Texas Rangers. But just like his older brother the president, now that he is a powerful elected official, Jeb Bush can’t seem to escape nagging questions about his time in the private sector.

The focus of the renewed scrutiny is Jeb’s partnership with David Eller, president and CEO of MWI Corp., a Florida-based water pump company. The Department of Justice is now accusing MWI of using millions in U.S. government loans, obtained from the Export-Import Bank, to bribe Nigerian officials to buy MWI pumps. The suit was originally filed by a former MWI employee in 1998. The government decided to intervene on the employee’s behalf earlier this year.

Eller, a major Republican donor and activist, formed a partnership with Bush in 1989 called Bush-El. The business was established to sell MWI pumps and other equipment in other countries. During his father’s presidency, Bush visited Nigeria twice as an MWI advocate. The visits from the first son were major events in Nigeria, according to media reports. There was even a parade, complete with 1,300 horses, in Bush’s honor. The St. Petersburg Times reported that “tens of thousands of people lined the road to welcome the American president’s son.”

Bush was in Nigeria to help sell millions of dollars worth of MWI products to the Nigerian government. According to a 1992 Wall Street Journal article, Bush was simultaneously working to arrange a visit to the White House by Nigerian President Ibrahim Babangida. “Jeb Bush’s experiences in the pump business provide a case study in how to profit from a Presidential name — perfectly legally, by all appearances,” the Journal wrote.

But the financing of the deal that came out of those visits was less than perfectly legal, the Department of Justice now claims. A government complaint seeking millions in damages against MWI suggests political influence played a large role in MWI obtaining the multimillion dollar Export-Import loans in the first place. In fact, the government suggests that Eller’s political connections were the primary reason MWI was able to secure government loans at all. Although the suit suggests the company cashed in on its political connections to help secure the government loans, it seems to go out of its way not to mention Jeb Bush by name. The suit notes that Eller did business with “a member of a prominent national political family in an attempt to bolster MWI’s sales abroad” — an obvious reference to Jeb Bush.

“MWI’s overt political activism and influence created both sales opportunities in Nigeria and ready access to [Export-Import] Bank loan support for those sales back in the United States,” the complaint says. “The fact that MWI was able to obtain Exim Bank Financing at all is surprising given the Nigerian Federal Government’s traditionally poor credit history.”

Bush spokesman Todd Harris denies any wrongdoing on the part of the governor, and points out that Bush’s opponents have tried unsuccessfully for more than a decade to use MWI as a way to attack Bush politically and it hasn’t worked. When the case was first filed back in 1998, Democrat Buddy MacKay tried to raise the issue in his run against Bush. “That was the only issue that they ran on,” says Harris. “They pushed and pushed on that issue, and Buddy MacKay got his butt kicked. But Democrats keep trying to bring it up.”

This time, however, it’s the Justice Department that’s bringing it up. And while the suit doesn’t target Bush, and Bush says he never profited directly from MWI’s dealings in Nigeria, it certainly raises questions about the business that made him his fortune.

The suit suggests that MWI and the Nigerian government manufactured the need for MWI equipment in Nigeria. The complaint consistently puts the word “need” in quotation marks when discussing the necessity of pumping equipment in the African nation. As the complaint points out, “MWI was not required to bid or otherwise compete with any other manufacturers to obtain any of its Exim-financed contracts,” effectively allowing MWI to set the price without any competition.

Obviously, such a deal would be beneficial for MWI. But why would the Nigerian government want to enter into this deal? The answer is at the heart of the government’s case. It claims these loans were improperly used to pay off Nigerian officials to the tune of $28 million. The government charges the bribes were delivered by a Nigerian MWI employee named Alhaji Indimi. According to the government, Indimi “has well-established relationships with high-ranking Nigerian state and federal officials which have provided MWI with the necessary access and opportunity to consummate Exim-supported sales in Nigeria.”

The government case cites one occasion when Indimi “carried large quantities of [cash]” to a meeting with Nigerian government officials. “Indimi and the other MWI officers and employees returned to the airport following the meeting without the currency … MWI officers and employees knew that Indimi was traveling with large quantities of cash, and believed that Indimi intended to and did use the cash to make payments to Nigerian State officials in connection with the MWI Sales to Nigeria,” the complaint states.

The complaint calls MWI’s payment to Indimi “excessive and highly irregular as to MWI’s own commission practices, as well as to normal and customary commissions.”

Eller’s attorney, William Scherer, has openly admitted that Indimi was paid nearly $28 million from the sale, but denied that money was used to bribe government officials. And he took umbrage with the government’s characterization of that payment — more than 37 percent of the entire $74.3 million deal– as excessive. “Who says that 30 percent is high (for commissions), especially when you’re talking about sales that took a decade to make?” Scherer told the St. Petersburg Times. “That’s absolutely and completely defensible.”

Bush himself is not implicated in the case. As a partner of Bush-El, he was just the salesman for MWI, and was not directly involved in the alleged fraud of the Exim Bank. And Bush has said repeatedly that he and Eller structured their partnership so that Bush would not profit off of any deals involving funding from U.S. government institutions. Since Bush’s father was president at the time, he says he was careful to avoid the appearance of cashing in on government contracts.

What became the government’s case against Eller and MWI was a lawsuit originally filed by Robert Purcell, a former vice president of sales for MWI. Purcell filed a separate suit in 1996 claiming MWI and Bush-El cheated him out of promised payments. In that suit, Purcell sought to depose Bush, but Bush’s lawyers were able to quash the subpoena because Bush was in the final days of his successful run for governor. As Bush’s lawyers pointed out in their successful motion to evade deposition, “whether by mere coincidence or by a tactical legal maneuver, the date on which Mr. Bush is to be deposed falls only 35 days prior to the November election.”

Soon after the election, the case was settled out of court. In this latest suit, Purcell stands to make a tidy sum if the government wins its case. The case indicates that the government may seek to recover as much as $220 million from MWI in damages. Under federal whistleblower laws, Purcell stands to gain 25 percent of whatever judgment the government received.

Though Purcell’s attorneys have included Bush on the possible list of witnesses to be called in the case, Eller’s attorneys maintain that Bush is irrelevant to the case and should not be called to testify. The Bush campaign says it has no reason to believe the governor will be dragged back into the case against MWI.

Jeb Bush insists he did not know of any bribes of Nigerian officials, and that he did not personally profit off any piece of the Nigerian deal. But the governor’s political opponents say Bush has failed to answer questions about what he did for Bush-El to merit nearly $650,000 he received from Eller when he ended the partnership in 1994. Bush has said that his Bush-El profits came from deals the company made in other countries, such as Mexico, that did not involve financing from any U.S. government institution.

Bush’s answer to the charges, the first time around, was a simple one. “Either you trust me or you don’t,” he told the Miami Herald in 1998. Harris says Florida voters are satisfied that Bush did nothing wrong, and said Bush has no intention of documenting his past business dealings with Eller.

Now that the Justice Department is involved in the case, Democrats are trying to use the lawsuit to score political points, once again calling on Bush to fully disclose what he did to earn the $648,250 Eller paid him. But while Bush has been candid about certain aspects of his financial past — he has, for example, released two decades worth of personal income tax records — he still has not answered reporters’ questions about the work he did for Bush-El. And, Democrats point out, Eller “hosted” a June fundraiser for Bush’s reelection campaign. Harris says Eller was simply one of more than 100 Bush donors who were listed as co-sponsors of the event.

Much the way his brother has evaded pointed questions surrounding his own business dealings during the 1998 Texas governor’s race, Jeb Bush has so far been able to duck tough queries about his association with Eller and the lawsuit against Eller’s company. And state Democrats’ inability to sell this story has become a symbol of how a race that was supposed to be one of the most competitive in the country has fizzled, leaving many national Democrats looking for other places to spend their time and money. Although Bush’s personal approval ratings have dropped since earlier in the year, he has maintained comfortable leads against both of his potential Democratic challengers.

Part of the problem is the state’s own Democratic Party, which is bitterly divided, with most party regulars lined up behind McBride. Polls show Reno is popular with Democratic primary voters, so she looks unstoppable in the Sept. 10 primary, but many Democrats fear she is unelectable statewide.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Democrats were hoping to harness lingering resentment from the 2000 presidential election, as well as blacks’ anger about Bush’s moves against affirmative action, into a crusade to dump Bush from the Statehouse in 2002. While early predictions had Florida one of the most contested gubernatorial races in the country this year, recent polling still shows Bush with double-digit leads over both McBride and Reno.

But any lingering Democratic anger from Election 2000 may be offset by tepid reaction to the party’s candidates. The party favorite, former ambassador to Vietnam Pete Peterson, took a pass on the race when Reno danced her way in. Democratic insiders, both in Florida and Washington, worry that Janet Reno is the Democrats’ Bill Simon — the wrong candidate in the wrong place at the wrong time, who is running a terrible campaign against an opponent — in Simon’s case California Gov. Gray Davis — who should be vulnerable. Still, some Florida political observers warn against labeling Bush a shoo-in. “I expect the race will be quite close,” says Darryl Paulson, a professor at the University of South Florida who expects Reno to win the primary easily. “I would be surprised if it’s more than 53-47 in the general. I think she has the potential to pull an upset. The most effective rallying cry for the partisans is some reference to the 2000 campaign, the stolen election.”

Paulson insists Reno or McBride have at least a fighting chance against Bush, because the 1990s changed the political makeup of the state dramatically. More than 1 million African-Americans moved to Florida during that decade, and the state’s non-Cuban Hispanic population continues to boom. Cubans, too, have begun to liberalize, a little, with younger voters less likely than their elders to demand hard-line anti-Castro stands. And Paulson says Republicans did not pay close enough attention to how Florida had changed when they made their calculations about the last presidential race, in which the governor’s brother required Supreme Court assistance to win a state he was supposed to carry by a landslide.

“The 2000 Election was a good example of Republicans being caught by surprise,” he says.

In the meantime, local Democrats are doing everything they can — including trying to tarnish the governor with the Justice Department’s suit against his former partner — to try to convince national Democrats that the race is in play.

“It’s the thing he just refuses to answer any questions on,” says Florida Democratic chairman Bob Poe. “He says he’s got nothing to hide, but yet he won’t tell us anything about it. That inconsistency is very troubling.” Like a lot of Florida Democrats, Poe links Jeb’s handling of his business past with the way his brother handled questions about his own questionable business deals. “He’s been hoping for a long time that people would forget and this would just go away, that if he just kept not answering, people would get tired of asking. That seems to be a trait in the Bush family.”

A Florida Republican Party spokesman accused Democrats of trying to drudge up phantom scandals from Bush’s past in an effort to tar the governor. And he said most Florida voters will ignore them. “They’re like the chatty bird up in the tree — people eventually start to ignore it,” said Florida GOP spokesman Towson Fraser. “Whether it’s true or not, or whether it means anything or not, people will eventually kind of tune you out.”

Not only have Florida voters tuned out the MWI story, but so have many national Democratic leaders. Several contacted by Salon admitted on background that they had never heard of the MWI story, and expressed doubts the story was the kind that could turn the Florida governor’s race around. The problem, they insist, is with their own candidates, and the lackluster campaigns they have run thus far.

“After 2000, everyone thought this would be a race we would be focusing on [in 2002],” said one Washington Democrat. “Now, it’s like, ‘There’s one less race we have to worry about.'”