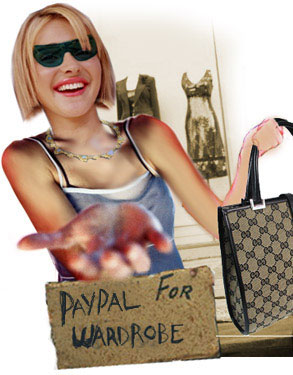

In June of this year, Karyn Bosnak bounced a $59 check at a grocery store. She was officially broke — unable to scrape up enough cash to get to work. Karyn looked rich: She was a television producer, earned $900 a week and lived in a stylish apartment in Brooklyn with a closetful of Gucci and Louis Vuitton. But she also had a $20,221.40 credit card bill (thanks mainly to the aforementioned Gucci), an empty savings account, and now, the fee for a bounced check.

That night, Karyn decided that it was time for a change. So she did what any 29-year-old, marketing-savvy woman might do if she had $20,221.40 in debt and no easy way to pay it back: She built a Web site, and simply asked people to help her out by sending her a buck or two.

Four months later, Karyn Bosnak is the world’s most successful Internet panhandler: At last count, she had paid off nearly $17,000 of her debt, thanks to donations of $1 to $1,000 from the thousands of strangers who have taken pity on her. Her Web site, SaveKaryn.com, has been visited by more than a million people; she’s been featured on the “Today” show and in People magazine; she’s been offered a book deal and a movie contract. Life is suddenly looking up for a woman who, just months ago, was “depressed and freaked out” by her financial straits.

Sitting at an outdoor cafe in Brooklyn, in a sheer DKNY peasant blouse and jean skirt, Karyn now beams with the beatific smile of the freshly famous. Her blond, highlighted bob glows in the sun; her cheeks are flushed pink with excitement. “I never in my whole life imagined this: ever ever ever,” she gushes. “I just so hit rock bottom that I didn’t know what to do, and I took a shitty situation and turned it around. I guess the lesson in that is don’t let life get you down.”

A more complicated lesson in the tale of Karyn Bosnak is that marketing is everything these days. Her radical approach to debt eradication is utterly generational, embodying all that is inspiring and much that is repugnant about the 20- and 30-somethings of the digital age — Karyn’s adventure is rich in self-entitlement, innovation, extravagant living and entrepreneurship. Her donors, most of whom come from the same demographic, practice a peculiar new form of individual philanthropy, in which donating is both a form of entertainment and a selfishly karmic activity. Karyn’s imitators, meanwhile, of whom there are many, exhibit a near-religious faith in advertising, believing that a strategy that worked well for one brand (Karyn) is bound to work for another.

“I think Karyn has succeeded in raising money because she captured people’s imaginations and is so obviously human — and because she made them laugh, which is a really powerful thing to be able to do,” says Lynette Webb, a 32-year-old media planner in London who donated $10 to Karyn’s cause. “As a general rule, I think people are so bombarded with pleas for handouts these days that a lot gets screened out. It’s only those campaigns that come along that have a personal resonance that get through — whether because it’s an issue you feel strongly about, or whether you just feel touched by the people involved.”

– – – – – – – – – – – –

The SaveKaryn.com Web site yields much information about Karyn the person: She is an open book. She is a woman who is fond of exclamations like “Nummy!” “CooCooCaChoo!” and “Yipee!” who uses “fun and light-hearted” as a mantra when describing herself and her interests. On her Web site, she makes pronouncements like, “A computer is a necessary part of being a human in today’s society. I cannot live without one. It’s kind of like undereye cream. It’s something that everyone needs.” In person, she comes off as professionally perky, easygoing, slightly gushy and, in a disarming way, winsome.

“I do not position myself as a victim because I know I got myself into it, but if I am, I think I’ve been a victim of a good economy,” Karyn explains. “I’ve been a victim of always having a nice paycheck. For me, this kind of slapped me into a reality that it’s not always sunshine and roses.”

Karyn grew up in the suburbs of Chicago, the younger of two daughters born to upper-middle-class parents who eventually divorced. She lived, she says, “a fun, great childhood,” attending a private Catholic school, spending summers on the family’s boat in Lake Michigan. Although she refuses to describe her family as affluent, she was certainly schooled in the ways of conspicuous consumption at a very young age. “In my school you just weren’t the cool kid if you had a Liz Claiborne clutch, you had to have a Gucci purse, or Louis Vuitton or something like that,” she explains. Her mother dutifully did all that she could to help her daughters fit in, buying them the necessary accessories when they were barely out of pubescence.

Karyn headed off to the University of Illinois for college, but finished up her marketing and public relations degree at Columbia and jumped quickly from a corporate job at Hyatt Hotels to a more “fun” job as an audience coach for “The Jenny Jones Show” in Chicago. The work suited her hyperactive personality: “I’ve got a lot of energy, I’m absolutely nuts; it was a great way to burn off my energy every day, clapping my hands,” she says.

By 2000, Karyn had moved to New York for a $75,000-a-year producer job at a courtroom television show called “Curtis Court.” Later she moved to a $100,000 producer job at “The Ananda Lewis Show,” a short-lived talk show featuring a former MTV VJ. When the show failed, Karyn was a casualty. By November of last year, she was unemployed, and discovering that in the post-dot-com post-9/11 economy, there weren’t a lot of jobs for TV producers or marketing types, no matter how energetic, fun or accomplished at clapping.

This might not have been such a big problem, were it not for the credit card debt that Karyn had been amassing while employed. Despite her enviable salary, she had not saved a dime. Instead, living in a $2,000-a-month apartment just blocks away from Bloomingdale’s, Karyn went on a series of extraordinary shopping sprees, charging a closetful of designer shoes and purses on her numerous credit cards. “I went kind of crazy,” she says, only slightly abashed.

Broke, unemployed and $20,000 in debt — unable even to afford a pedicure, she sighs — Karyn was a very unhappy camper indeed. “I think a lot of women, whether you’re high-maintenance or not — you identify who you are with what you look like. It was kind of like, when I couldn’t color my hair, couldn’t do all these things, I kind of got depressed for a while. I couldn’t go out and buy cute clothes, I just felt funky every time I went anywhere, in like old clothes, stuff like, ugh. It’s just weird, but it’s true!” she says, surveying her jean skirt and proclaiming that today she feels “frumpy.”

Karyn finally “snapped out of it,” and began living a frugal life — rarely going out, shopping only at Old Navy if at all, cooking for herself, moving to a shared apartment in Brooklyn. Still, even after she got a new job (for half the pay) on an Animal Planet TV show about New Yorkers and their pets, she says she was living hand-to-mouth. Finally, the fateful bounced check triggered a moment of desperation and inspiration, and SaveKaryn.com was born.

There is no subterfuge in the site that Karyn invented in June of this year — she posted a humorous plea for donations, forthrightly explaining her situation, Gucci shoes and all. “If 20,000 people gave me just $1, I’d be home free, and I’m sure there are 20,000 people out there who have been in my position who can afford to give me $1, who know how I’m feeling,” she explains. “That’s all I was thinking: that there are nice people, and if people just shared, and if all these wealthy people gave their money to people like me, the economy would be better, it’d be a better place. That’s it! If we just kind of balanced out a little bit.”

Call it incredibly naive, or incredibly optimistic, but amazingly, it worked. She added a chatty personal diary to the site that documented both the donations she received and her attempts to reduce her living expenses. She also opened an eBay site, where she began auctioning off her designer clothes. The initial trickle of donations grew as the URL was passed around — many people, apparently, found Karyn’s jaw-dropping ballsiness amusing; and then the site exploded as it began showing up in USA Today and the New York Times. The week of Aug. 18, during the peak of publicity, she received $2,630.84 in donations and $682.46 via eBay. Although most donors just chipped in a few dollars, one anonymous donor ponied up a generous $1,000.

In her closet, where the Gucci purses once sat, Karyn now keeps a large plastic bin filled with letters that people have sent her; her bathroom is overflowing with the vanity products — creams, lotions, shampoos, allergy medicine — that her adoring readers have sent as consolation. She’s received teddy bears, subscriptions to Vogue, Dunkin’ Donuts coupons, backpacks, jewelry, cat food, candles, even two free pairs of boots from Chinese Laundry. It’s hard to fathom why so many people would spend time and money to help a total stranger pay off her appallingly extravagant spending sprees, but they do: Something about Karyn’s story, or approach, or both, clearly hit a nerve.

Why do they do it? Karyn has been asked this question by dozens of reporters, and she has a pat answer ready. “I was just honest about what happened; I didn’t make up some sob story about saving the world,” she explains, shrugging. Her donors think it’s funny, and original, she argues, and view it less as a charity than as an entertainment site.

Comments from her contributors suggest that she’s right. “I donated $5 because as far as entertainment value was concerned, her site was worth at least what it would have cost to rent a DVD for the evening,” says 27-year-old Ralph Pickering, a network engineer. “It made me smile.”

It’s also revealing that so many of her donations came from young, Net-savvy people, the same demographic that, like Karyn, has been hit hard by the crash of the dot-com economy, and, as a result, can closely identify with her plight. A quick flip through her letters turns up countless donors who confess their own credit card debt, their own unemployment, and their hopes that a buck for Karyn is essentially a buck for themselves: As one woman put it in a letter, “Maybe I’ll get reciprocal karma.”

Benevolence, where Karyn is concerned, becomes a curious form of selfishness. “I truly believe that what goes around comes around, and that by doing good deeds things will work out for me in the end. It’s the ‘Pay It Forward’ theory,” says 29-year-old unemployed Stefani McMurrey, proprietor of SMartHats.com, who gave Karyn $1. Like Karyn, McMurray has maxed out her credit, and is currently living off her home equity loan; she sees Karyn as a kind of soul sister in debt. “Karyn and I would be great friends, and I’m sure we’re a lot alike,” she says.

This is a common refrain from Karyn’s contributors: She is the everywoman of a specific market share, a contrite shopper who you would want to hang out with, who you would want to be your friend. It takes a certain lack of pretentiousness to confess your mistakes to thousands of strangers; and in the age of corrupt CEOs and underhanded ethics, Karyn’s blunt approach is appealing — and familiar — to many.

“I think Karyn is filling some kind of vacuum the baby boomers have created in our society. In a country where everyone seems to blame everyone else, or offer excuses for their actions, she’s actually accepting responsibility and doing something about it. She’s admitting her errors to the world and asking nicely for help,” says Jay Konieczka, a 27-year-old research scientist who gave Karyn $2 despite being in “even more debt than she is.

“I, for one, am starved for people like Karyn,” he says.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

Karyn was not the first person to put up a Web site asking strangers for money. The practice has a name — “cyber-begging” — and one directory called the “Amazing Send Me A Dollar Webboard” had documented 69 cyber-begging sites as of last August, including a 1999 site called “Save the Suburbanites” for a couple that wanted to raise money to quit their jobs and travel for a year (they cleared a mere $61), and the “Amazing Gimme a Buck (Please) Website,” which raised $65.31 for its owner. Most sites received little traffic and even less cash, perhaps because they lacked the humor or sympathy of SaveKaryn.

Karyn’s closest compatriot online is probably Todd Rosenberg, the proprietor of the Odd Todd Web site and an earlier “Today” show darling. Last year, after losing his job at the Web site Atom Films, Rosenberg began posting cartoons online that made light of his unemployment. Like Karyn, his plight hit a nerve; through a PayPal link and “Odd Todd” merchandise, Rosenberg managed to collect $15,000. Unlike Karyn, however, he couched the solicitation as a “tip” for his cartoon, rather than an outright donation (even if fans ultimately knew that this was what it was).

Karyn, on the other hand, has made no bones about the fact that she’s simply begging for a dollar to cover her debt. And as her site has rocketed to fame, imitators have sprung up all over the Net, some with even more outrageously selfish requests. If Karyn can get $20,000 to cover her Gucci tab, why can’t some other person, say, get people to buy me a BMW, pay for my breast implants or buy me a house? There are even satirical sites like Don’t Save Karyn and Save the CEO, who purports to need money to move his company to Mexico.

Most of these sites are pale imitations of Karyn’s, and have, not surprisingly, raised little to no cash. Those that tell more sympathetic stories do slightly better. Help Me Leave My Husband, a woman who wants to go to nursing school so she can afford to raise her family after her upcoming divorce, has raised $2,173.51. And HelpJennifer, the site of a 24-year-old Canadian woman with Lyme disease, has managed to raise a little more than $4,000 to cover her $50,000 in hospital bills.

Jennifer Glasser of HelpJennifer confesses that she was inspired by Karyn’s site: “I thought if someone was willing to give her money for that, that someone must be willing to give me a hand: I didn’t get into this through shopping; it was out of my control.” Her own rather sincere site has received money primarily through readers of her blog and friends she’s met online. “I was concerned that my site wasn’t entertaining or gimmicky in some way, and maybe people wouldn’t donate because of that,” she says.

Those who have given to Jennifer, though, tend to gravitate to her simply because her needs are “worthier” than Karyn’s. Says Nicolas Lambros, a 32-year-old restaurateur who gave Jennifer $30, “I read about Jennifer only after I read about Savekaryn.com and decided Jennifer’s purpose was the better way to go.”

Lambros is not alone in his distaste for Karyn. For all of Karyn’s fans, she also has thousands of enemies; people who send her hate mail and lambaste her on Web sites; those who fought to get her removed from eBay, and who point to her as the poster child for all that is wrong with dot-com-era self-entitlement. Karyn says she doesn’t let this anger bother her: “They are probably jealous they didn’t think of it,” she explains. “Seeing someone get success out of something that seems funny, like, ‘I was the biggest screwup, and I’m getting success out of it?’ That upsets people.”

Jealousy may be a factor, but outrage fuels many, if not most, of her detractors. “What really burns us is how she got into debt: all these nice things,” says Scott Dolce, proprietor of the anti-Karyn site SaveKarynnot.com. “I wish I could go blow a lot of money on stuff, but never in a million years would I ask other people to pay it off.” Instead, his site points its visitors to charities that benefit a wider swath of the population — the March of Dimes, the Red Cross, the Salvation Army.

Yet, it is the opaque nature of these larger charities that has motivated many donors to spend money on Karyn and Jennifer. The need to know the specific impact of charitable dollars became a huge issue after Sept. 11, when donors to the Red Cross felt swindled somehow when they couldn’t find proof that their money was being given to 9/11 widows and not the average impoverished American. Donors to Karyn watch her debt diminish; donors to Jennifer feel connected to their victim of choice. Witness Karyn’s boxes of communiqués from donors, full of intimate confessions from total strangers who clearly felt some kind of personal connection to her.

This is a particularly Webby form of giving; not merely because technology like PayPal and e-mail make it easy to find and give to the needy online, but because the Net has primed its regular users to be open to connecting with strangers. “I think there is a sense of community online that makes you more inclined to believe the best of people, and be willing to help someone out,” said Lynette Webb, the London media planner who donated to Karyn. “The whole spirit of newsgroups is based on that. Also the file-sharing community.” (It’s also rather naive, considering how easily the whole thing could be a hoax; but few people seem to worry about this.)

At least one new charity has decided to capitalize on the strange dynamic of Net giving: Modest Needs, a nonprofit organization launched in May by Keith Taylor, a philanthropy-minded professor from Middle Tennessee State University, has collected some $83,000 via PayPal that Taylor, in turn, distributes to individuals who need help. If you need, say, $300 to help you through a one-time crunch or an emergency — unexpected medical bills, car accidents, school book purchases — Taylor will assess your request and dispense cash from the general fund; of the 9,395 requests he’s received, he’s been able to fund 294 of the most “legitimate.” (Credit card debt, incidentally, does not qualify.)

“Modest Needs is not about some corporation, building some hospital,” says Taylor. “All those things are good things, but when you look at requests that are actually funded, those are individuals whose lives were changed for a small amount of money. That’s solidarity.”

And instant gratification all around.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

It seems unlikely that the cult of giving that Karyn inspired is going to last long. The sites that sprung up in her wake are not bringing in nearly as much cash. And although Karyn plans to “pass the buck” once she pays off her debt — handing her site off to another person who is trying to raise money — the momentum is already dissipating, and donations have dropped dramatically in the last few weeks.

The Web, so quickly jaded, is already moving on. “It certainly is a new type of benevolence, but unfortunately for any imitators, things on the Web get old really fast,” says Ralph Pickering. “But who knows? Maybe it’ll become a new sort of addiction, like eBay is to many people. Or maybe we’ll find homeless people handing out business cards with their PayPal account details.”

In the meantime Karyn, with her own debt nearly paid off, has capitalized nicely on her experience. She’s selling the rights to her life story to a major motion picture studio, she says, and is also in the process of selling a book about her experiences to a publishing company. It’s a curious career — being famous as a beggar — but despite her critics, she’s not at all chagrined about what she did.

“A lot of people say, Where’s your pride at? You should work hard and pay it off! I have pride, but when did it become so horrible and shameful for somebody to ask for help?” she says. “I see this as a proactive thing to get rid of my debt: It’s a lot of work to upkeep the site. I’m not filing for bankruptcy and sitting on my ass. It’s a funny Web site, and I’m proud of it.”

And will Karyn “pay it forward” when her debt is retired? She’s donated some money in the past, she says, $20 here and there to the ASPCA and Catholic charities, and if she gets the book deal, part of the money will go to charities. She’s eager to help other individuals, she says: “I think of people as all good people, and if I had a lot of money and ran across some girl who was in a position I’d been in before, I’d find it funny, I’d laugh, and say, ‘Here you go,'” she explains. “That’s what I would do if I had a lot of money: I’d help someone out.”

But Karyn’s magnanimity has its limits. On the way back from coffee, when we are stopped on the street by a vaguely surly young man in jeans and sneakers who asks us for a dollar to get on the subway to “get to school,” she pauses. Ever the savvy self-marketer, she weighs her decision carefully, knowing full well that a reporter is standing next to her and waiting for her response.

“Sorry,” she finally tells the man, and walks on, glancing out of the corner of her eyes at me. “That’s going in the story, isn’t it,” she says, flatly. I ask her why she didn’t give him a dollar, and she responds with confident self-righteousness: “He was crusty, and smoking a cigarette,” she explains. “That dollar wasn’t going to go toward the subway.”

She’s probably right, but I have to wonder: If he’d confessed that the buck was really going to go toward a six-pack of beer, would she have reconsidered her decision? It seems doubtful. In the world of Karyn and her circle of friends, the generosity of strangers seems to turn on a giggle and a plight that a Web-linked peer can relate to. Crusty beggars looking for subway money just don’t have currency in Karyn’s world, where a worthy cause is a “funny” “sweet” girl with a Gucci jones. It is about branding — in all things.

Karyn heads home guilt-free with a smile on her face, knowing that today she is blessed; that when she gets home another box of letters and cash will arrive in the mail; that an offer for a book deal will be on her voice mail; that the economy is finally looking up and so is she.