On Friday, John Philip Walker Lindh is scheduled to appear at a federal courthouse in Alexandria, Va., for a sentencing hearing likely to mark the end of his strange odyssey. The judge presiding over his case is expected to hand down a 20-year prison term in step with a plea agreement arranged by Lindh’s attorneys with U.S. prosecutors in mid-July.

And it should come as no shock to Lindh, who himself long saw something like this coming even before he was caught fighting for the Taliban in Afghanistan last year, according to one of Lindh’s former peers at a school for would-be jihad fighters in a rural Pakistani outpost.

“He said he was sure he would be punished when he returned to America,” said an 18-year-old who goes by the nom de guerre “Talha.” He is a Pakistani fighter with the underground Islamic militant group Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, or “Movement of Holy Warriors,” which Lindh briefly joined in the summer of 2001 before signing on with the Taliban.

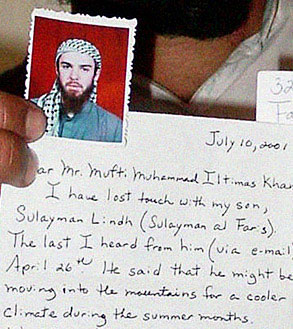

Talha, speaking through a translator, said he knew Lindh by his two aliases, Abdul Hamid and Suleyman al-Faris, when the two trained together at one of the group’s guerrilla camps in Mansehra, a small mountain town in northern Pakistan sitting just west of Kashmir, the disputed Himalayan region bordering India.

Training with at Harkat-ul-Mujahideen in the summer of 2001 was Lindh’s first real effort at jihad, or Islamic holy war. Lindh had spent roughly six months studying the Quran at a hardscrabble madrassa in Bannu, a small Pakistani village near the Afghan border, before first volunteering to fight Indian forces controlling areas of disputed Kashmir. He signed up with little ado at Harkat-ul-Mujahideen’s then legal recruitment office in Peshawar, about 80 miles northeast of Bannu. There, the group’s recruiters questioned him during several days of interviews before sending him off to basic training in Mansehra, according to court documents detailing Lindh’s own admissions to federal investigators. It was a routine procedure for thousands of Mujahedin volunteers both foreign and native.

That started his affiliation with Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, which emerged as a force in the Kashmir insurgency in 1994 and quickly grew to become one of the largest and most feared of Pakistan’s many militant organizations. By 1997, the group had earned a ranking on the State Department’s list of foreign terrorist organizations and taken on an especially dark reputation for its alleged involvement in several bloody kidnappings, including the abduction and murder of Wall Street Journal correspondent Daniel Pearl in the early weeks of 2002. In that case, Harkat-ul-Mujahideen is believed to be involved along with another militant group named Jaish-e-Mohammed, or “Army of Mohammed.”

Throughout the late 1990s, Harkat-ul-Mujahideen worked closely with the Taliban, according to Talha, Hamid and others in the group, as well as Taliban documents recovered in Kabul after the Taliban lost power. Harkat-ul-Mujahideen and its sympathizers effectively ran an underground jihadi railroad that stretched from Kabul and Kandahar to Shrinagar, the city in Indian Kashmir used by militants from Pakistan as the main staging ground for their Islamic insurgency against New Delhi. Harkat militants and holy war volunteers from sister organizations like Jaish-e-Mohammed traveled a network of madrassas and training camps that stretched through India, Pakistan and Afghanistan, where the group’s work with the Taliban at times overlapped with terrorist activities of Osama bin Laden, who of course Lindh would eventually meet.

Talha, whose splotchy black beard seemed to be falling off rather than growing in, remembered Lindh fondly as we sat last spring in a cramped Mansehra guesthouse near the camp, which was closed by Pakistani authorities after Sept. 11. “Our instructor introduced [Lindh] on his third day at lunch,” he said. Thumbing grimy pink plastic prayer beads, Talha at times sounded wistful as he spoke about Lindh.

“When we were sitting at lunch or dinner we would all try to sit next to him,” Talha said, describing how the light-skinned American drew the curiosity of his fellow jihadis.

When Lindh first arrived in Mansehra, about 400 young Harkat-ul-Mujahideen volunteers like Talha were already undergoing physical training as well as combat lessons and religious instruction at the group’s camp just outside town, where several other militant organizations ran similar operations with support from the Pakistani military.

Talha and other Harkat-ul-Mujahideen trainees in Mansehra at the time said they liked Lindh, though he struck them as odd. Lindh was the lone foreigner among the militants in that particular Harkat-ul-Mujahideen class; the rest of the volunteers in training at the time were Pakistani. Lindh could only talk to other trainees with the help of an instructor who spoke English as well as Urdu and Pashto. What struck them as particularly odd, however, were Lindh’s expressions of empathy for the Kashmir cause.

“One evening in the camp we were sitting with our brothers from Indian-held Kashmir,” said Talha. “They were telling us the problems they faced there,” Talha said. “One said his brother was killed by the Indian army. Another told how his sister was raped. As they told their stories, the man who cried the most was Abdul Hamid.”

The refugee group session that night was but one part of a training regimen lasting 24 days. The course was meant to ready would-be holy warriors both psychologically and physically for bloodletting in Indian Kashmir, where Muslim guerrilla fighters from Pakistan have helped wage an insurgency against the largely Hindu forces of India for the past 12 years, at the cost of an estimated 35,000 lives.

On a typical training day, according to Talha and other classmates, Lindh and his fellow recruits awoke before dawn to gather at the camp mosque, where they opened their Qurans and recited verses until the first of the day’s five calls to prayer sounded. After morning worship, the instructors put recruits through two hours of physical training that involved running and calisthenics. Then came breakfast, eaten quickly before arms lessons taught by mujahedin tutors, who schooled trainees in the use of pistols, Kalashnikovs, explosives and guerrilla tactics.

“We taught assembling and breaking down weapons,” said camp instructor Hamid (also an alias), a beefy man in his late 20s. “We also taught weapons techniques,” said Hamid. Peering over tiny square glasses with a smoky tint, Hamid said that the group had remained inactive since the police crackdown in 2001.

“In the same class, we taught how to handle weapons and how to fire as well as guerrilla warfare skills,” said Hamid. “We only train in small arms. We also taught night fighting skills and ambush strategy.”

In the afternoon, the students sat for academics, studying Islamic history and law. The classroom sessions lasted until late in the day, when students were given two hours of free time. After that, trainees gathered again at the mosque for an informal meeting ahead of dinner, which ended shortly before the call to evening prayer.

To close each day the volunteers all gathered at night for what they called an “accountability session,” in which the instructors encouraged trainees to air grievances they had with their colleagues, and to resolve issues or conflicts that arose in the ranks.

“We didn’t allow anyone in the camp to abuse or have a quarrel with someone else,” Hamid said. “If someone has a complaint about another volunteer, he stands up and voices it in front of the group. Suleyman [Lindh] never complained about anyone, and no one complained about Suleyman.”

Although Lindh seemed to have won loyalty and friendship among most of the volunteers, he failed to earn respect as a soldier from his instructors, who frequently found him struggling to keep up.

Talha remembered Lindh being late for many workouts.

“When we had physical training, those who came late were punished by the instructor,” Talha said, describing how tardy trainees were ordered either to do pushups or crawl long lengths, combat-style, wriggling over rocky ground on stomach and elbows.

“[Lindh] liked the punishment,” Talha said with a wincing smile.

Most of the volunteers at the camp who completed the basic training either went on to advanced guerrilla instruction at another one of Harkat-ul-Mujahideen’s many camps or formed small bands that slipped into Kashmir, roughly 10 miles from Mansehra. Some volunteers, either unwilling or unqualified for fighting or more training, simply drifted back to regular life, which in most cases meant more studying at madrassas like the one Lindh attended.

But none of those paths appealed to Lindh, who at some point apparently grew disenchanted with the conflicted politics of the Kashmir insurgency and saw the Taliban’s Afghanistan as a more righteous spiritual calling. That was fine with Lindh’s Pakistani instructors, who deemed him too weak and unskilled for their purposes anyway.

“We have a procedure for advanced guerrilla training,” Hamid said. “We send only handpicked volunteers for that training, and Sulayman didn’t qualify. We chose the stronger volunteers. Most of them are from hilly areas. Sulayman was from an American city. He was soft. We pick volunteers with a lot of strength and endurance. Sulayman was not fit enough.”

The Mansehra course nonetheless gave Lindh enough training to be considered for grunt duty in Afghanistan, where much of Harkat-ul-Mujahideen’s work was meant to aid the Taliban in its long-running war against the Northern Alliance.

“We train volunteers in the most basic skills they need in Afghanistan,” Hamid said. “One doesn’t need advanced guerrilla training to go to Afghanistan because the war there is not so difficult. The enemy is in front of you and you’re shooting at him. But war in Kashmir is the most difficult. You need advanced training to fight there. You face the enemy on all sides in Kashmir.”

Shortly after Lindh’s Mansehra training ended, Harkat-ul-Mujahideen instructors handed him over to the Taliban, sending him across the border and onto Kabul with a letter of introduction.

“We sent him to our Peshawar office and they arranged his trip to Afghanistan,” Hamid said.

Talha and others were sad to see Lindh go when he left Mansehra at the end of May 2001.

“We didn’t want him to go to Afghanistan,” Talha said. “He said he had seen the mujahedin and that he wanted to go to Afghanistan to see the Islamic environment.

“He said he was not going there to fight,” Talha added. “He was just there to see the Islamic environment.”

What exactly Lindh did when he joined the Taliban is somewhat in dispute, and will not be aired in court, since a plea bargain made a trial unnecessary. But when he left Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, Lindh was headed straight into the last and most controversial part of his trip through Central Asia. He would be with the Taliban for roughly six months before he was finally captured by U.S. forces Dec. 1, 2001.