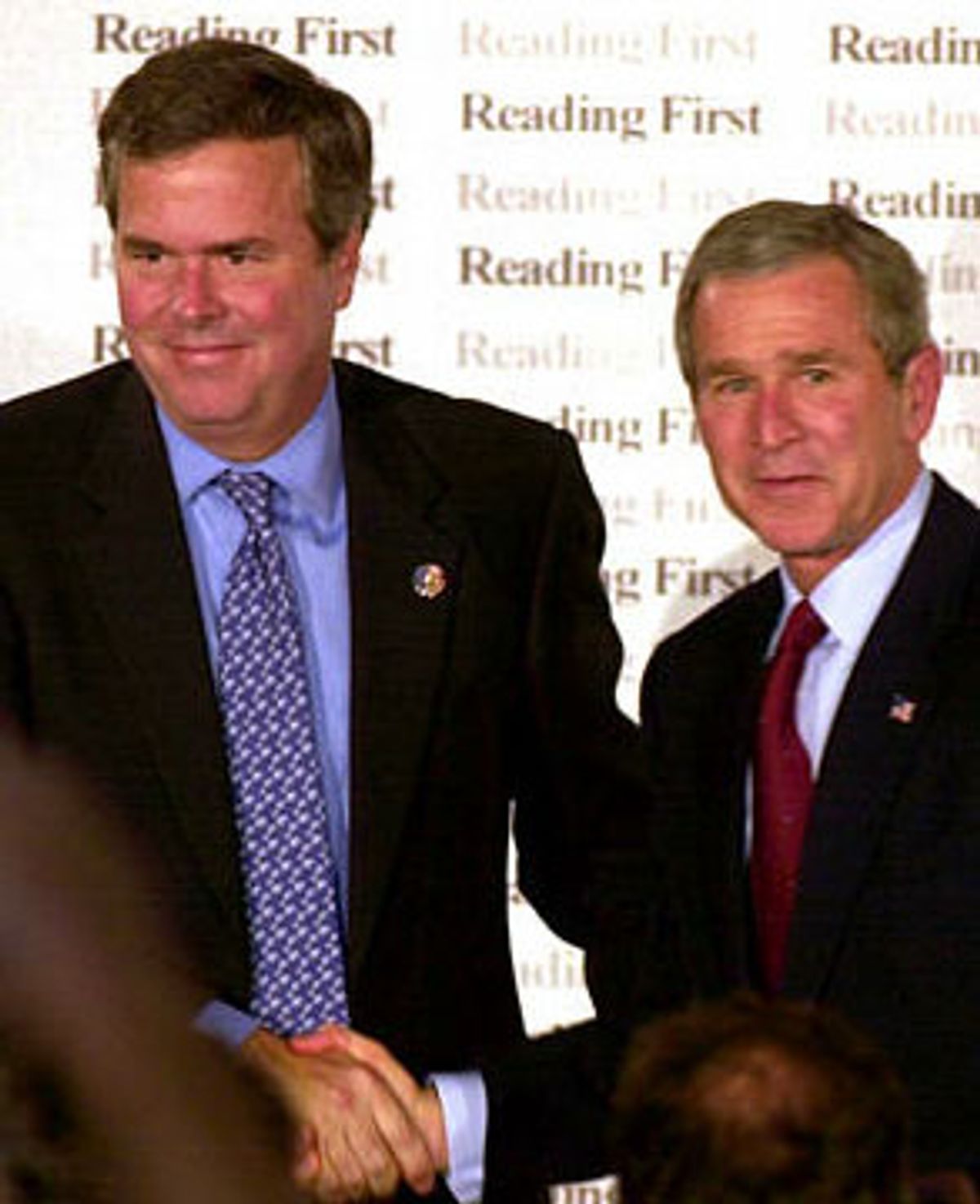

His famous brother in the White House has been doing everything he can to help, showering Florida with all sorts of federal goodies over the past 18 months. And he has unrivaled riches in his war chest, enough to power a small national campaign. But the polls don't lie: For all his advantages, Jeb Bush finds himself in a Florida dogfight.

On paper, Jeb Bush should be the clear favorite to become the first Republican in the state ever reelected governor, adding another victory for the Bush dynasty. But Bush has been dogged by embarrassing family problems, by deep lingering resentment over the 2000 election fiasco -- and by Bill McBride, a cash-poor Democratic challenger who refuses to go away. A political novice, McBride will receive some high-profile help Saturday when former President Bill Clinton arrives to campaign, the same day President Bush barnstorms in Florida for his brother.

Jeb Bush is having to work hard and spend lavishly in the last few days of the campaign. He holds a modest lead in many polls, but McBride, the folksy Vietnam War hero, has kept the race close and, backed by the national Democratic Party, has rolled out a batch of tough new ads pounding the governor at the close of the campaign.

Even many Republicans say it didn't have to be so close. Bush, the policy wonk of the family who earned a bachelor's degree in Latin American studies in just three years while making Phi Beta Kappa, has created an extraordinary power base in Florida, transforming the governor's office into one that wields unprecedented power in the Sunshine State. "Combining the power of the White House and the Governor's Mansion, the Bush family reelection machine is unmatched by anything that has ever happened before in Florida politics," the Palm Beach Post recently noted.

Despite that kind of firepower, Democrats want to believe they have a shot in Florida, where voters are divided into camps of those who love Jeb Bush and those who loathe him. "In some states you can't talk about religion or abortion. In this state you can't talk about politics because everybody's made up their minds," says Steve MacNamara, a professor of political science at Florida State University. "You're either for Jeb or you're not."

Many are not. They're still upset about the 2000 Florida recount, when Jeb Bush's office made nearly 100 phone calls to George Bush's campaign and its advisors after Jeb had officially recused himself from any involvement. They also want to send an embarrassing message to the White House, which has dispatched President Bush to make nearly 70 campaign appearances down the stretch (including one in Florida) as it tries to turn the fall elections into a national referendum on the president's performance.

"There won't be anything as devastating to President Bush as his brother's losing in Florida," Democratic Party chairman Terry McAuliffe recently boasted, insisting McBride would have the necessary resources at his disposal. The Republican national party has not backed down from the challenge, pumping $2.5 million into Bush's coffers last July and August alone. Having a Republican governor, not to mention a Bush brother, at Florida's helm will be crucial during the president's reelection run in 2004. It certainly helped in 2000.

Jeb Bush entered his reelection race somewhat tarnished and took some early hits, which quickly invited in-house second-guessers. "I could have given the governor a pretty good blueprint to follow where this would be a double-digit race so far," Florida Republican Party chairman Al Cardenas told the Gannett News Service two weeks ago. "But that's not how he wants to do it."

Going back to 2000, the fact that Florida even had to recount its ballots underscored how Bush failed to deliver a state widely assumed to be safely in the Republican column. Meanwhile, the governor has fought bruising statewide battles over affirmative action, the environment and education, while having to answer a string of accusations about ethical lapses and cronyism.

"His own workers are frothing at the mouth at the chance to vote against him," says Doug Martin, communications director for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees council, which represents 70,000 of Florida's public employees. The organization has spent $1 million in an effort to defeat Bush, the biggest commitment in the union's history. "Jeb is not someone who harbors dissent. Instead he cooks things up in secret and then rams it through the Legislature. He thinks he's king."

Bush has not been improving that image lately. In October, while jawing with Republican legislators, he bragged that he had a "devious plan" to circumvent a popular education amendment on this year's ballot that mandated smaller classes. Bush opposes the amendment. His foot-in-the-mouth blunder -- Bush was unaware a credential-wearing reporter was recording the back-and-forth with GOP pals -- made headlines, and it is now featured prominently in a McBride commercial.

The episode reminded some people of Bush's gaffe in 1999 when, in the midst of a statewide debate over affirmative action, two black lawmakers refused to leave the lieutenant governor's office. Bush dismissively ordered an aide to "kick their asses out." That too was caught on tape.

Closer to home, Bush's family has appeared at times to be coming unglued. His daughter Noelle continues a very public battle against drug addiction. His wife, Columba, was fined $4,000 for not paying duty on $19,000 worth of clothes she bought on a trip to Paris. Bush himself last year had to publicly deny a rumor he was having an affair with a state appointee, while his 16-year-old son Jebby was caught by police having sex with a girl inside a parked car in Tallahassee.

At the same time, challenger McBride, with a sterling business reputation and a no-nonsense character, emerged as a potential giant slayer. With the help of a crucial teachers' union endorsement, McBride rose from obscurity last spring to become the Democratic nominee this fall. In the process, he spoiled Republican plans for Bush to run against the more liberal Janet Reno.

The son of a TV repairman, McBride played running back on the University of Florida football team and then went to Vietnam, where he led a combat platoon and won a Bronze Star. Later, as a lawyer, he rose to become the high-powered, well-connected managing partner at Holland & Knight, turning the law firm into one of the largest in the country. He also lost some clients over the firm's progressive policies, such as providing benefits for domestic partners. Meanwhile, some Holland & Knight lawyers grumbled about all the pro bono work McBride insisted the firm take on.

With a famous Republican incumbent up against a plain-talking moderate who's capable of keeping "Old Florida" Democrats from crossing over to the GOP, it shouldn't be a surprise that polls for most of September and October showed the race a statistical toss-up. "Florida is such a polarized state politically, we're used to extremely close races and being at each other's throats," notes Republican strategist and lobbyist J.M. "Mac" Stipanovich, who managed Bush's first run for governor in 1994.

"It's still a close race according to our internal polling," says Alan Stonecipher, a spokesman for the McBride campaign. "If people would've told us that 10 days to go we'd be within the margin of error at the end of the campaign, we'd have taken that."

Bush supporters play down any talk of an upset. Steve Uhlfelder is a Tallahassee lawyer and Florida State University trustee who went to college with McBride and worked at the same law firm, but he's backing Bush. "With less than two weeks, I don't know what Bill can do," he says. "Bush has more money, better resources, and the 2000 recount is not overshadowing the race like Bill thought it would. Maybe I'm missing something, but I don't see the momentum shifting. Bill McBride is going to need an earthquake on a major Richter scale to win the election."

One constant in Florida politics is there's always a possible earthquake rumbling in the form of the black voter turnout. During the 2000 election, blacks who were fuming over Bush's decision to dismantle state-sponsored affirmative action came out at the major Richter scale rate of 80 percent -- and 93 percent of them voted for Al Gore. To win, McBride needs another presidential level-type turnout of 65 percent or higher, particularly in Palm Beach, Broward and Miami-Dade counties in South Florida to offset Bush's certain advantage upstate.

"There's a real anger in the African-American community," reports Randolf Bracy Jr., pastor of the New Covenant Baptist Church in Orlando. "The people I serve feel like the last election was stolen."

A new anger erupted this week when 200 Haitian refugees, caught trying to swim ashore in Miami, were detained for deportation. Leaders in South Florida's black community berated Bush on the campaign trail, asking him why refugees from Cuba are routinely allowed to stay in Florida, but Haitians are not. Bush enjoys strong support from Florida's conservative Cuban community.

But McBride's relationship with the black community is somewhat strained. During the primary season he essentially ignored them, conceding their votes to Reno, and worked instead to secure support in Central and Northern Florida. Since then, McBride has been traveling regularly to black churches seeking their help, but his choice of running mate, another white middle-aged lawyer, did him no favors in that community.

"There was some grousing," concedes Martin at AFSCME, which has a large minority membership. "An African-American running mate certainly would have helped."

"I don't think McBride can get the African-American turnout," says MacNamara at FSU, who notes Bush won 14 percent of the black vote in 1998, an unprecedented showing for a Republican candidate in Florida. "If Jeb wins 15 percent, McBride doesn't come close," says MacNamara. "But if Bush only gets single digits and the turnout rate is 65 percent, then they could be counting ballots into December."

Some partisan Democrats have been clamoring for former Vice President Al Gore or for Clinton, who is working behind the scenes to raise money for McBride and urging black ministers to get out the vote, to personally campaign in Florida. "William Jefferson Clinton energizes black voters -- period," says Bracy.

Even as late as this Wednesday there were still no plans for a Clinton visit. The unspoken assumption was that the McBride camp was concerned an appearance by Clinton would activate the black base but turn off crucial swing voters. "That's a mistake," insists Jim Eaton, a lawyer, lobbyist and longtime player in Florida Democratic politics. "Clinton is not that polarizing of a figure anymore." That logic came to prevail by Thursday: Clinton is now scheduled to appear at three get-out-the-vote rallies Saturday night and possibly make additional appearances Sunday morning. "He is a master at motivating Democrats," says the McBride campaign's Stonecipher.

That's the kind of news that keeps hope alive for McBride and his troops. It helps to keep the race competitive down to the wire. "If McBride has an effective, last-minute ad campaign -- something that grabs voters' attention and sways swing voters -- he can win," says Susan MacManus, a professor of political science at the University of South Florida. "But it's going to be tough."

Still, some observers are wondering whether it's already too late. McBride's performance in last week's debate was less than impressive. Then, some say, the press seemed to turn on him.

"He didn't deserve the pounding he took in the newspapers after the debate," says MacNamara, a veteran of state Republican politics. "The press likes to keep the race close, but in the end none of them want to cover a McBride governor. They want to cover a celebrity governor, the brother of the president of the United States. It's human nature."

Bush, with $12 million remaining from a $30 million campaign fund, meanwhile saturated the airwaves, labeling McBride a tax-and-spend threat. McBride, with only $1 million in the bank, had to hold his fire for the final push.

Before his batch of sharp new ads debuted, several Florida newspapers started a new round of polling. From McBride's perspective, the results were grim: Bush enjoys a lead of between six and eight points, his biggest margin in months.

Worse, the St. Petersburg Times/Miami Herald poll showed Floridians picked Bush as the better candidate to improve public education in Florida. That result was startling, considering that McBride's entire campaign has centered on the classroom and his accusation that public education under Bush had tanked, with test scores falling and class sizes bulging.

"He's run the education issue into the ground and it hasn't moved the needle," notes Towery at InsiderAdvantage, who once served as Newt Gingrich's campaign chairman. Nonetheless, Towery says McBride's new ads paid dividends in overnight polling last weekend, and he dismisses talk that Bush has the election wrapped up. "I think it's going to be extraordinarily close," he says. "If I had to guess, I'd say right now Bush is at 47 and McBride 42, and everything else is up for grabs."

Yet those odds look longer today for McBride than they did two weeks ago. "Jeb was beatable. He's passing special-interest tax breaks for friends, cutting social services statewide, and the state surplus is gone," notes Miami Herald columnist Jim DeFede. "Coming out of the primary McBride had this image of a giant slayer, while Jeb fucked up left and right. But McBride never built up any momentum."

There's also a feeling that the down-home McBride, who has described his campaign for governor as a job interview, did not effectively take the fight to Bush, did not articulate a reason why voters should drive him out of office. "Jeb has all the king's horses and all the king's men, every weapon in the modern arsenal of politics," Eaton says. "If you're going to beat the juggernaut, you have to be aggressive. If Bill McBride comes up short on Election Day, it will be because he didn't get after Jeb Bush."

Shares