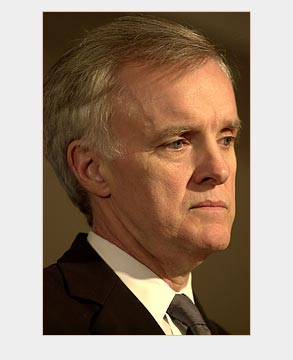

Bob Kerrey is a fierce critic of the administration’s unilateralist bluster. A former Nebraska Democratic senator and president of Manhattan’s progressive New School university, he’s also a decorated Vietnam veteran dogged by excruciating memories of combat and accusations about his role in a massacre, and he knows that a war with Iraq will be expensive and painful. “We civilians cannot expect to liberate 25 million Iraqis on the cheap,” he wrote in the Wall Street Journal Sept. 12. He believes our current military might is enough to deter Saddam from using weapons of mass destruction. He says President Bush has weakened the country’s credibility by failing to commit enough troops to maintain some semblance of order in Afghanistan.

So why is he part of a new group created to sell the invasion of Iraq to the American people?

Along with former Secretary of State George P. Shultz and Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., Kerrey is part of the newly formed Committee for the Liberation of Iraq, a group meant to shore up support for regime change. Unlike Democratic hawks in Congress, he has little to gain politically by getting behind this war, and he doesn’t have to pretend to have much respect for Bush’s leadership. He’s involved, he says, because he believes the U.S. has a moral duty to get rid of Saddam, and he wants to convince liberals that this war should be their cause.

Kerrey, in fact, has been calling for regime change in Iraq for years. In 1998, he was a co-sponsor of the Iraq Liberation Act, which enumerated Saddam Hussein’s crimes and said, “It should be the policy of the United States to seek to remove the regime headed by Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq and to promote the emergence of a democratic government to replace that regime.” He points out that Bush, at the beginning of his term, floated the idea of ceasing patrols of the no-fly zones protecting Shia Muslims in Southern Iraq and Kurds in the North, effectively abandoning our military presence in Iraq.

So it’s not that he’s following Bush’s lead, but the other way around.

On Sept. 12 you wrote, “Given all the other assignments –particularly the war in Afghanistan which is by no means over, and the risk of conflict between Pakistan and India, which has by no means passed — we are not ready to conduct a successful war to liberate the people of Iraq.” What has changed?

In September we were simply not prepared. We’ve done a substantial amount of organizing since then, not just militarily but diplomatically. This needs to be a multinational effort. The administration wasn’t close to the kind of diplomatic success they needed [in September]. We’re not ready today — you couldn’t make the case you could do it today — but preparation is under way.

The polls show that support for a war against Saddam is diminishing. A recent Pew poll has it down to 55 percent from 64 percent. What’s affecting public opinion?

I don’t know. I think in part what has gone down is [support for] unilateral action on the part of the United States. The polling info I’ve seen shows support for a multilateral effort.

There are lots of misunderstandings about the circumstances surrounding this effort in Iraq. If you polled Americans and said, “Are you aware that the United States has for 11 years been participating in a multinational military effort against Iraq [in the no-fly zones] and we may have to sustain it forever,” most wouldn’t know. We have a moral burden that’s different than most other countries. We’re not picking Iraq because we’ve just decided that’s what we want to do. There’s been a policy of containment in place since 1991 and we’ve been enforcing it with substantial military action.

Does that moral burden come from our support of Saddam before 1990?

No, it does not. It may come in part from that, but that would not be sufficient to justify changing our military strategy today. The moral burden comes from answering the question, “What if we stop flying military missions in the North and South?” The French were flying missions and they quit. The Bush administration was thinking about [quitting] when they first came to office. But the day we stop, Saddam Hussein moves seven divisions north and a lot of Iraqi Kurds die. America and Britain share the burden of knowing they have a very bad set of options. We can continue doing what we’re doing, putting our pilots at risk. We can change our strategy to eliminate the need for military action, or we can stop military action altogether.

If we cease military action, Iraqis are going to die. That’s the burden on us.

So humanitarian issues are paramount in your argument for war?

Yes. I blame the Bush administration for not successfully making that case. The president has emphasized to a fault the threat to America, but the threat to America is far less important a justification than the case that I just made. The moral justification for war is the correct justification. It’s not nuclear, biological and chemical weapons — deterrence works there. We have enough force capability to deter Iraq from using any weapons of mass destruction.

Ahmed Chalabi, the head of the Iraq National Congress, reportedly has been promising Iraq’s oil to various American companies. Doesn’t this undermine the credibility of the Iraqi opposition?

No more and no less than congressman Mike Oxley [R-Ohio], taking a million dollars from the financial services industry and then chairing the House Financial Services committee, undermines Congress. Damage to political credibility is a constant and Chalabi is no exception. I don’t think Chalabi has much chance at all of being democratically elected in Iraq, but it’s a false choice to undercut the moral authority [of the INC]. It’s one of those attacks typically made by people who want to fail to liberate Iraq.

Most experts seem to agree that rebuilding Iraq is going to take billions of dollars, hundreds of thousands of troops and several years. Bush hasn’t prepared the public for that kind of commitment. Aren’t you worried that once America overthrows Saddam the public will insist we pull out as soon as the costs get too high, leaving the country in chaos?

Oh sure. That’s a real worry. The worry is connected to the 2000 presidential campaign, when Bush was saying we’re stretched too thin and he favored pulling troops out of Bosnia. We’d gone through years of waiting, waiting, waiting [while the genocide in Bosnia went on]. We’d heard that quicksand argument — that they’d been fighting for hundreds of years, that we couldn’t solve the problem of ethnic rivalry. We finally overcame that after the hell of Srebrenica. We organized a multilateral force and today you can fly to Sarajevo and shop there. Prior to that we had diplomats dying there. And in spite of that success, Gov. Bush was saying we ought to get out of Bosnia?

The fear that America will not stay the course is justifiable. However, it cuts against those who argue that America has this great imperial ambition. People who want America to be constructively engaged in the world should fear our isolationist tendency more than our interventionist tendency. You don’t have to go any further than Afghanistan to see that.

But isn’t the chaos engulfing Afghanistan an argument against invading Iraq?

It argues only that we should intervene correctly. It’s false that this is a choice between intervention or no intervention. We have intervened. We’ve been intervening for 11 years with limited success. President Bush was thinking about stopping the intervention in Iraq, stopping this quite dangerous and expensive military operation that has pilots flying these no-fly zones. It’s not terribly constructive to criticize Bush for that other than to make the point that Americans are far more reticent to use military force than the world thinks we are.

Then why does the world see the United States as such an aggressive bully?

With all we’ve done to tell the world we’re going to go it alone, saying no to Kyoto, to the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, the International Criminal Court … We said no to immigration reform to help Mexico, and then we’re surprised that Mexico might not vote with us on the Security Council? If you go out and tell the rest of the world you’re willing to go it alone and your dominant concern is your own safety and security, don’t be surprised if the rest of the world isn’t interested in participating. If you say our dominant concern is the people of Iraq, that we understand it’s got to be multilateral — we need Arab participation — we’re much more likely to get other countries’ support.

So would you still support a war on Iraq if the U.S. were alone?

It’s unlikely that that would happen. But given all the other things going on in the world, if we went in unilaterally, the risk is too great we’ll stop [before its finished] and the risk is too great we’ll fail. But that situation is very unlikely — though [a few months ago] that sure as heck was where we were headed.

What can we do to help repair our credibility in the eyes of the world?

We need to expand our military presence beyond Kabul, to accelerate training of the Afghan army, to do everything we can to support the democratic development of that nation, to recognize it’s going to be exceptionally difficult and to take a long time.

Given the triumph of Islamist parties in elections in Turkey and Pakistan, how likely is it that elections would result in a fundamentalist takeover of Iraq?

Democracy is a risky venture. The National Socialist Party was elected in 1933 in Germany, a nation that was highly educated, producing a tremendous number of Nobel laureates. Democracy is risky, but the case we need to make is that you can have an Islamic party but favor a secular government. You see it being made in nations like Turkey. That argument is increasingly being made in Iran. Democracy is tough, but it’s a hell of a lot better than the alternatives. I don’t like what happened in the midterm elections. Does that mean we shouldn’t have democracy?

I love that we’re on the side of freedom in Iraq. We’re saying Arabs have the capacity to govern themselves — a few years ago people were saying just the opposite. If you stretch back and examine the argument in 1998, you had people saying in response to me, “There’s no Thomas Jefferson in Iraq.” Well, there’s no Thomas Jefferson in the United States. Our job isn’t to pick an Iraqi leader; it’s to let Iraq pick a leader.

Are you saying that the argument that democracy won’t work in Iraq is racist?

It’s not just racist and condescending, but part of it is racist and condescending. If you look at what’s happening north of the 36th parallel in the Kurdish country, they’re saying we’re tired of killing, and they’re building democratic institutions.

But the Kurds aren’t dealing with ethnic divisions right now. Once Saddam is gone, isn’t there a possibility the country will devolve into a bloody civil war between the Shia, Sunnis and Kurds?

Is it possible you can have a bloody civil war? Sure. I think it’s unlikely, but it’s always the fear when you’re talking about trying to organize democracy. We had a bloody civil war in the United States, an awful one.

[What’s going on in Kurdish country] is cause for hope, not cause for despair. I think we can make this a success. If we are successful at liberating Iraq and five years from now you can go to Baghdad and the people of Iraq thank you on the street because you lifted their standard of living, you’ll find very few people who will say [it was a mistake].

There are all kinds of problems with an operation like this. There are all kinds of things that could cause us to fail. There’s no shortage of things I think the president has done wrong, but in my heart I agree with what he wants to get done, so I’m on this committee, and I’m going to stay the course.

The other day I was talking to an Iraqi exile who is in graduate school at Harvard. He was in Iraq during the first Gulf War. He hates Saddam, but he doesn’t trust the United States at all. He points to our support for murderous regimes in Chile and Argentina and our support for the Shah of Iran and for Saddam in the ’80s, and he says he believes the United States is going to establish a military junta in Iraq and exploit its oil. Why should he believe that the U.S. government cares about making life better for Iraqis?

He’s been listening too much to his Harvard professors. You can’t reach back in American history for the worst mistake we ever made and use it as a rationalization not to try something good.

I could go back and say, “Look what we did in Guatemala.” It was a great tragedy of the Cold War. But we learned from our mistake in Guatemala, even though we airbrush what happened there.

I don’t blame [the Harvard student] at all. I could make a stronger case based on things the United States has done in Iraq since then that, if I were in Iraq, would cause me not to support the United States. We tried to organize the Kurdish opposition in ’95 and ’96, and we weren’t there when fighting got real serious. I remember what happened when the United States promised to be with them.

[Because of what we’ve done,] I don’t think we will necessarily be welcomed in. But if it’s multinational, especially with Arab participation, there’s no doubt if we stay the course and produce this liberation, the Iraqis will be grateful.

We know what a terrible thing we did after the Gulf War to encourage Iraqis to rise up and then not follow through in helping them. But you can’t take the worst America has done and then cite it as reason not to try and do anything good. Unfortunately that argument is all too common among liberals.

Why do you feel liberals should support this war?

Do liberals care about freedom? Do they care about human rights and repression? These are central to our core values. How is it not possible for us to come out in favor of the need to liberate Iraq, to walk away from the truly racist policies that aligned us with dictators because they satisfied our economic interest? Liberals should be embracing this change. Unless liberals do, it’s likely to be done wrong.