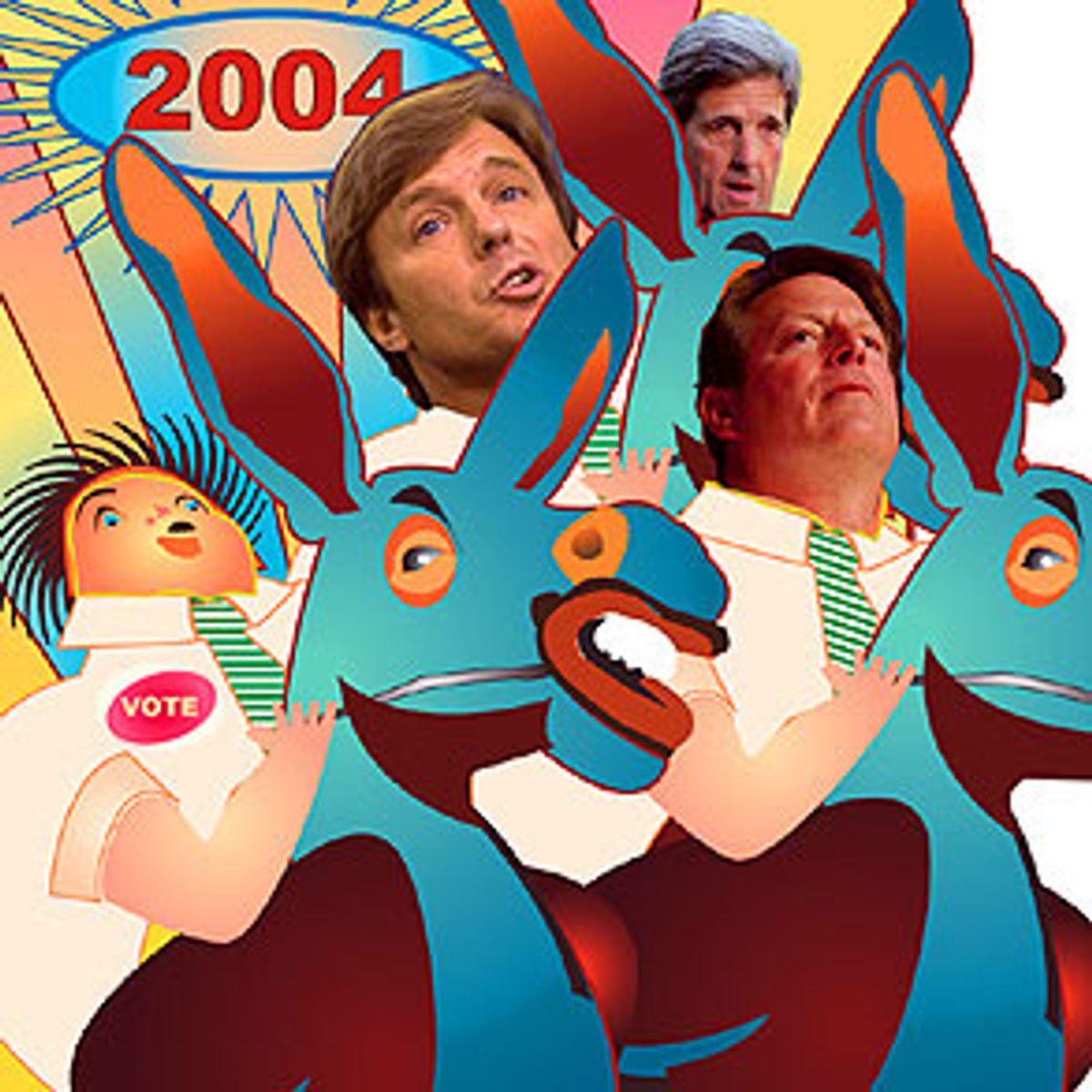

The Democratic Party has three presidential wannabes with one big problem -- most voters couldn't pick them out of a lineup. While Sens. John Kerry, D-Mass., and John Edwards, D-N.C., and Vermont Gov. Howard Dean try to overcome the recognition problem, Al Gore is wrestling with his Al Gore problem. While Edwards, Kerry and Dean worry about what we'll remember, Al Gore desperately wants us to forget.

Friday night Gore kicks off a heavy media offensive, part of his efforts to re-create himself in time for 2004, with a prime-time interview with Barbara Walters and a late-night visit with David Letterman. But he'll be joined soon enough by a new crop of unknowns that are already earning their own early buzz.

There's Iowa Gov. Tom Vilsack, who's become the long-shot pick of former Labor Secretary Robert Reich. And in a sign of just how profound the party's identity crisis has become, former Colorado Sen. Gary Hart even stoked the fires of speculation about his political comeback last week, though it's likely that has more to do with a future Senate run than a third White House bid. On the far left, Rev. Al Sharpton and Rep. Dennis Kucinich, D-Ohio, are both said to be considering bids. And after being cast aside by Georgia voters, and her party, Rep. Cynthia McKinney, D-Ga., is said to be considering a run for president, perhaps on the Green Party ticket.

Yet the race has already seen its casualties. Sen. Tom Daschle, D-S.D., ruled out a White House bid after his party lost control of the Senate last week. And poor election day performances by a pair of governors -- California's Gray Davis, who squeaked out an ugly win, and Roy Barnes of Georgia, who lost the party's 130-year hold on the statehouse -- have diminished their presidential hopes.

Others sit in limbo: Rep. Richard Gephardt, D-Mo., fresh off House Democrats' big losses in the midterm elections, is letting some of that sting, and whispered abuse from his colleagues, subside before formally announcing his presidential bid, but it seems hobbled from the start. And Sen. Joe Lieberman, D-Conn., is relegated to the sidelines, sitting in a political trap of his own making, having vowed not to run if Al Gore seeks the nomination again.

And so, the Democrats for now are left with a six-pack of candidates lining up for the two-year quest for the White House.

Al Gore: To some Democrats, Al Gore figures in this race like a dentist appointment -- inevitable, perhaps, but not a whole lot of fun to sit through, and with the very real possibility of a painful ending.

Nobody wants to be the next Al Gore this time around, including Gore himself. In an effort to erase memories of his lockbox-toting, Buddhist-temple fundraising, truth-stretching, no-controlling-legal-authority invoking former self, Gore is taking a different approach. Friday, Gore begins a soft launch to his presidential campaign. First he'll appear opposite Barbara Walters (Gore aides assure us that no tears were shed), then he'll stop in with David Letterman.

Next week, he and his wife, Tipper, will begin a 12-city campaign swing masquerading as a book tour, ostensibly to promote their co-written book "Joined at the Heart," which is paired with the photo book "The Spirit of Family." Sometime in between Letterman and next month's "Saturday Night Live" appearance, Gore will begin formal interviews with political reporters from the major newspapers.

But just what Gore's message will be remains something of a mystery. His criticisms of the Bush administration's focus on Saddam Hussein had more to do with the timing of it than the substance. And what was billed as his major economic critique would foreshadow the problems his party had in last week's election: While punctuated with one-liners aimed at the administration's economic policies, Gore's speech was woefully short on solutions.

Still, most say the nomination is still Gore's to lose. "Al Gore is the wild card in this thing," says Democratic political consultant Hank Sheinkopf, a veteran of the 1996 Clinton-Gore team. "The question is, do Democrats coalesce around Al Gore if he wants it? Can they tell Al Gore no? Probably not."

While Gore's aides insist he has not yet made up his mind about his presidential ambitions, the coming media blitz would certainly suggest another presidential run is in the offing. But Democrats say their party's problem is not simply the party's muddled message, it's finding an effective and attractive messenger. And they fear that Gore is damaged goods.

Though there have been some defections, Gore maintains a loyal core of advisors who have continued to offer counsel during the last two years, among them consultants Carter Eskew and Mike Feldman, policy advisor Sarah Bianchi and fundraiser Peter Knight.

John Kerry: Kerry's challenge, in a nutshell, is to prove that he's more a maverick with widespread appeal like John McCain than a ringer à la Michael Dukakis with little appeal outside of the Northeast corridor. As Republican consultant Ron Kaufman said of Kerry's presidential bid this week, "I don't think God is good enough to give us another Massachusetts Democrat to run against."

If Kerry is geographically challenged in the world of presidential politics, he does have other things going for him. He's a Catholic, which may help Democrats among a key swing constituency in Midwestern battleground states. And he is a proven fundraiser who happens to be the richest of the Democratic millionaires seeking the nomination.

But Kerry hopes to differentiate himself through his biography. Kerry's aides say his candidacy will largely be built around his personal story: He's a Vietnam veteran who returned home to become a leader of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War. To help promote that story, Kerry has signed up historian Douglas Brinkley to write a book about Kerry's time in Vietnam, tentatively titled "Tour of Duty: John Kerry and the Vietnam War," and scheduled for release next fall.

Kerry has been a critic of the administration's foreign policy, and of the military's execution of the war in Afghanistan, but he voted in favor of the resolution that authorized force against Iraq. In the Senate he has been an environmental champion, leading the fight to increase fuel efficiency standards in cars and reduce American dependence on foreign oil. He also, along with Lieberman, led the effort to block administration plans to drill for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. And hey, he's also the only candidate in the field who has dated Morgan Fairchild.

But some Democrats say his wife, Teresa Heinz, the heiress to the Heinz condiment fortune, may be a political liability for Kerry. They point to a Washington Post story earlier this year in which the couple bickers in front of the reporter, and Heinz imitates her husband having a nightmare about Vietnam. ("'Down! Down, down!' she yells, patting her hands down on her auburn hair.") Perhaps that's why she has hired a new spokesman, former CNN White House correspondent Chris Black. The New York Daily News quoted a Kerry source as saying Black's hire was meant to help "rein in Teresa" before the presidential campaign begins.

With the economy emerging as the mainline of the Democrats' critique, Kerry is planning to outline his vision for the economy sometime in the next few weeks in what one aide says will be "more detail than we've seen from the other candidates to this point."

But Kerry will have to overcome his own Gore-like tendencies. It's not uncommon for Kerry to pepper casual conversation with Latin phrases, and he's articulate, but he's not known as a dynamic speaker. The team around Kerry was put in place long ago, and they've been itching to get going for months. Senate chief of staff David McCain and communications director David Wade are set to head to Boston where they'll be joined by other Kerry veterans Jim Jordan, executive director of the Democratic Senate Campaign Committee who will run Kerry's campaign, and Michael Whouley, a Gore 2000 veteran who worked for Kerry before the 2000 campaign.

John Edwards: The media is a fickle mistress. Before Americans have even met Edwards, Washington reporters have already swooned over him, lashed back against him, and now may be swooning again.

Edwards was the recipient of glowing profiles by Christopher Hitchens in Vanity Fair, and Nicholas Lemann in the New Yorker. A U.S News and World Report cover with the headline "Who Can Beat Bush" featured Edwards' mug. But after a lackluster May 5 appearance on "Meet the Press," whispers began about Edwards' readiness for the big time. And while Lemann hailed Edwards as a trial lawyer populist, fellow New Yorker writer Joe Klein was less kind in Slate.

"There is another, more colloquial expression used to describe Edwards' line of work," Klein wrote. "Ambulance-chaser." The New Republic even published a tongue-in-cheek guide to the Edwards backlash to come.

Despite his brief ride in the media wash cycle, Edwards remains, for now, the charismatic, Southern fair-haired boy of the party.

Both in substance and in style, Edwards is reaching for the mantle of Clinton. There has even been speculation that Clinton is tacitly supporting Edwards, since key members of Clinton's fundraising and grass-roots organizing teams have lined up behind the North Carolina senator. His recent economic treatise read like a Democratic Leadership Council memo, focused on the kind of fiscal discipline Clinton championed after losing Congress in 1994. In the speech, Edwards laid out his economic plan, railing against both the Bush tax cut and congressional spending.

"You know why Americans think many Democrats want to spend too much money? They do. You know why Americans think many Republicans are too close to corporate interests? They are," Edwards said. "We cannot meet these challenges unless we get serious about controlling spending. That means spending on pet projects and on pet tax cuts."

Freed from the confines of the midterm election, Edwards was able to do what Gore was not in Gore's recent talk on the economy -- explicitly call for the rollback of Bush's $1.3 trillion tax cut. Edwards' plan did not name specific programs he'd place on the chopping block. Instead, he called for the streamlining of government waste, and cutting the federal payroll while maintaining bumps in defense spending -- not exactly revolutionary proposals, and ones that would only begin to address the budget problems now facing the country.

Somewhat predictably, the DLC hailed Edwards' speech, and some liberals said it missed the mark. Robert Borosage, director of the liberal Campaign for America's Future, said the speech "showed that he's probably not ready for prime time." Edwards' position as a fiscal conservative, Borosage says, is taking the wrong lessons from Clinton's message, which was a plan for a growing economy, not a shrinking one. "Clinton called for paying down deficits not as a principle of economics, but as a way to stop Republican tax cuts," he said. "Given the problems we face now, I don't think it's good policy, and I don't think it's good politics."

With his personal charisma and Southern drawl, some Democrats have eagerly tagged Edwards as Clinton's heir apparent. Aides are sensitive to criticism that Edwards' four years in elected office do not exactly make an impressive résumé of public service. But Edwards will continue his efforts to bridge the gravitas gap with a major education speech next week, and a trip overseas to meet with NATO leaders in December.

If regional background is Kerry's weakness, it is John Edwards' strength. Like every other Democratic president since 1964, Edwards is from the South. But Democrats' weakness in the South during the midterm elections, particularly in Edwards' home state of North Carolina where Elizabeth Dole whooped Erskine Bowles, has many Democrats concerned about what an Edwards presidential bid could mean for the security of his Senate seat.

His rivals whisper that Edwards' flirtation with a presidential run after only four years in elected office may hurt his chances of holding the seat "That's nonsense," Sheinkopf says. "There's plenty of time to stick your toes in, see what the waters are like, and then get out." But already, Republicans are eyeing the seat when it comes up in 2004.

Richard Gephardt: In corporate America, it is not uncommon for ineffectual midlevel executives to be kicked upstairs and given a grandiose title with little responsibility where they can do the company no harm. If this were the case with the office of president of the United States, Richard Gephardt would have odds for the 2004 race.

If and when Gephardt enters the presidential fray, he will first have to battle the new image cemented for him last Tuesday -- that of a leader whose failure to articulate a clear vision for his party led to Democratic losses on Election Day. Though he has been a prodigious fundraiser, and helped Democrats make steady gains in the House since he became minority leader after Democrats lost control in 1994, Tuesday's results ensure Gephardt will be known as the man who failed to take back the House, and who stemmed the historical tide and lost seats in this year's congressional elections.

But if Democrats are looking to break left in the wake of last week's defeat, Gephardt may receive a boost. While he has attempted to moderate his stands somewhat as minority leader -- witness his rush to embrace the president's Iraq war resolution -- Gephardt's Midwestern populism and labor roots make him perhaps the most liberal of the mainstream Democratic contenders.

Still, if Gephardt is to get any traction, he's going to have to get last Tuesday's "loser" stamp off his forehead. Doubts about Gephardt's leadership ability began the day after the election, when he got a hearty, and very public, shove out the door from one of his House colleagues. But when Rep. Harold Ford Jr., D-Tenn, announced that Gephardt should hit the road, Gephardt's aides suspected Ford was simply doing Al Gore's dirty work.

"Harold Ford is a charter member of the Gore for president committee," the aide told the Washington Post. "He's always been the guy they go to to do their business. When they need someone to criticize Dick, he's always first in line."

Despite the recent setbacks, Gephardt could be a formidable candidate when he officially enters the race. His strong ties to organized labor should be a boost in a Democratic primary, and he would likely run well in the first caucus state of Iowa. In fact, Gephardt won the Iowa caucuses in 1988 during his first, failed presidential bid.

Joe Lieberman: If it weren't the Sabbath, you can bet that somewhere in Stamford, Conn., Friday night, a television screen would be glowing, tuned in to the Al Gore double feature.

Lieberman has said repeatedly that he would not run for president if Gore decides to run again, and his staff says they are essentially on hold until Gore makes his intentions known. When asked if Lieberman might consider a run if Gore gave his blessing to a challenge from Lieberman, Lieberman spokesman Dan Gerstein said, "It wouldn't make a difference. He's not budging on that."

While Gore, Edwards and Kerry clamor for the media spotlight, Lieberman will be laying low for the next few weeks, Gerstein says. "I think he's taking some time to think through the implication of the elections," Gerstein says. "He's doing some thinking about if he's going to run for president, and what that's going to be all about. But I don't think he's going to be active in the next few weeks."

As Lieberman sits and waits, Gore will be sucking up the media spotlight, while Edwards shoots for Lieberman's support from Democratic moderates. "He's not losing any sleep over this," Gerstein said. "He certainly doesn't view the Senate as a consolation prize."

Gore, though, is hardly Lieberman's only problem. Red-meat Democrats remember well how Lieberman -- in both his sole vice-presidential debate with Cheney and during the Florida recount -- refused to take off the gloves. And among liberals, he's frequently portrayed as too pro-business -- and way too sanctimonious.

Howard Dean: Dean ran out ahead of the pack, becoming the first candidate to open a presidential exploratory committee this summer. He also set out to distinguish himself on the issues. When he announced his presidential bid, he also announced he would focus on the issue of healthcare. While the early start gave Dean a small smattering of media attention, it also led some Democrats to dismiss his candidacy as a single-issue crusade instead of a bona fide presidential bid.

For now at least, Dean remains the only governor in the field, and Democrats don't exactly have a great track record lately of electing senators to the White House. Though, as Kerry staffers would undoubtedly add, the last senator who was elected to the White House was a Catholic Democrat from Massachusetts. But if Democrats are truly hungry for a fresh face, that may well lead them to take a good hard look at Dean.

Like Kerry, Dean must overcome the notion that he is just another Northeastern liberal. But he has begun to assemble a campaign staff, announcing this week that he has hired former Democratic National Committee chairman Steve Grossman to help him raise money for his presidential run. He is scheduled to announce a campaign manager later this month.

The Others: As the Democratic Party continues its post-election soul searching, the old struggle for the direction of the party is sure to play out in the presidential primary. Of course, Ralph Nader took enough votes from Gore to cost him the presidency in 2000, and liberals within the party view that as a sign that they must have more of a voice within the confines of the party.

Kucinich, an Ohio Democrat and pacifist who was one of Gephardt's most vocal House critics for stifling debate on the Iraq issue, has contemplated a presidential bid. As has Al Sharpton. "People underestimate how smart he really is, and how savvy," says Sheinkopf of Sharpton. "It won't be like Jesse Jackson in 1988. Jesse was a Southern preacher. Sharpton is an urban prophet. That message is going to resonate with a lot of Democrats."

A lot of Republicans sure hope so.

Shares