The map of child abuse can be obvious on a young body — purple fingerprints on a pinched forearm, yellowed welts on the back, a hairline fracture in a wounded wrist.

The ravages on a child’s psyche are murkier. Will a victim grow to be timid? Angry? Unfocused? Suicidal? Why do some abused children revisit violence on their own children while others manage to become loving parents?

Some of these questions remain unanswered, but the psychological damage may be more specific than we have imagined. A new generation of researchers relying on controlled experiments and current technology have begun to discern abuse’s path through the physiology of the brain.

Seth Pollak, an assistant professor of psychology, psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, has found in his cutting-edge experiments that abuse so profoundly alters the mechanism of the mind that the perception of reality itself is notably different for abused children than for the rest of us.

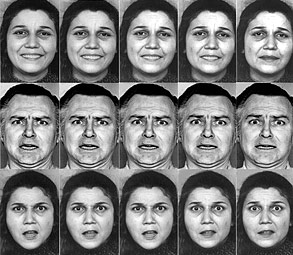

Pollak and colleague Doris Kistler found in a recent study that children with a history of abuse tended to interpret ambiguous facial expressions as angry far more frequently than a control group of children.

In the experiment, set up as a computer game, 40 children aged 8 to 10 years old were asked to categorize the emotions of a series of digitally morphed faces expressing varying degrees of happiness, fear, sadness and anger. While the children generally responded the same to faces showing mostly happiness, sadness or fear, abused children identified more of the ambiguous faces as being angry, rather than fearful or sad. In an earlier experiment, Pollak found that brain wave activity increased when abused children viewed images of angry faces.

Pollak theorizes that abused children adapt to their dangerous environments by developing a kind of early warning system — a hypersensitivity to any possible signals of anger — that helps them avoid injury. “I think people become hypersensitive to the emotions that are most salient or significant in their lives,” says Pollak.

It’s an excellent survival mechanism; the trouble is that children who continue to interpret benign signals as threatening in all situations — even outside an abusive relationship — may react inappropriately and trigger major social problems the rest of their lives. Pollak believes the trick is to teach these children how to change their response when they’re free of their abusers.

Pollak spoke to Salon recently from his office in Madison about his experiments, the canny coping mechanisms of children, the ways we can help abused children, and what troubles his grad students.

How is your work different from others studying abused children?

Typically, child abuse is seen as a psycho-social child development problem. We’re recasting it as a problem of brain development. Instead of looking at child abuse just as a social problem, we’re really looking at this problem from the perspective of the brain systems involved in perceiving information from the world. And we’re conducting experiments — controlled experiments — to do so.

We’re learning about things we wouldn’t have seen without these approaches — things like specific ways in which children are perceiving faces. If we just asked them to tell stories, or observed how long they sat on a parent’s lap, we wouldn’t get this kind of information.

You showed the children facial expressions depicting varying degrees of happiness, sadness, fear and anger. How does a face communicate an emotion?

It’s a wild process. We think of recognizing a facial expression as easy. And in fact, even very young infants can do it. But the process of recognizing a face is actually very complex. You must first perceive all of the different patterns of muscle activation in a face — mouth, eyes, forehead, cheeks, eyebrows — and then somehow put all of those different muscle movements together. Then you need to relate that pattern to other times you have seen it, to your previous experiences. Then you need to generate some sort of label to identify it. In many cases you need to relate what you are seeing to the context. It’s amazing that the human brain can do this in milliseconds.

In other studies, you measured children’s brain waves as a way to understand how they recognize emotions.

We had wires attached to the children’s heads in a soundproof room. If I had children actually on the playground, I couldn’t get those kinds of measurements. Most researchers have gone more naturalistic, less about the biology. We need both.

Why did you look specifically for reactions to anger?

We chose to focus on anger because my theory is that young children can’t attend to everything that’s going on around them, and because of that, they have to be selective. They have to attend to the most salient things in their environment.

There are a number of emotions that an abused child could see a lot of — like fear or sadness. But I think if you had to focus on just one emotion, anger would be your best bet. By the time you notice someone is feeling scared, an abusive experience has already begun, something scary is happening. But noticing that an adult is becoming angry might allow a bit of extra time to prepare for a violent episode.

Also, abusive parents are not always hostile. It could be very difficult to pick an abusive parent out of a crowd. The problem is that these people tend to have the proverbial short fuse. They can be interacting with their kids normally and then become very hostile in a sudden or extreme way. In a way, these parents are very unpredictable.

In our experiments, normally treated kids responded as one would expect — similarly to anger, sadness, all those basic emotions. The physically abused kids only differed in the response to anger, both in their sensitivity or ability to detect emotions and in their brain activity. But they all looked the same when they were responding to other emotions.

In the past, most research on child maltreatment simply listed all of the problems and deficits these kids have, without acknowledging what may be an adaptive aspect to their behavior. I have a totally different take. I think the abused kids are doing what you would want them to do.

How is it a good thing?

What made it a really interesting study was that these kids are picking up on something that really matters in their lives. If I had done this experiment and the abused kids had generally performed worse, that wouldn’t have been interesting because that would have been just another example of the things maltreated kids can’t do.

In the past, the literature has really focused on all the problems these kids have. The argument that I want to make is that I think you have to look at this as an illustration of both adaptation and maladaptation. When these kids are living in these hostile home environments that are abusive, then this hypervigilance is adaptive in letting the kids survive and cope.

This is a skill that kids carry everywhere. The difference is context. At school, these kids are with kids who aren’t hurting them, teachers who aren’t abusing them. So the idea here is the strategy. Processes that work very well in one context, when a child changes context, in a place where people aren’t harming them, all of a sudden that doesn’t work.

You’ve mentioned tailored interventions to help abused children. Can you explain what you think might help these kids?

I’d like to see less “shrinky” stuff and more psycho-educational stuff. Instead of therapists trying to be good “attachment” figures and trying to change the “representations that children form of Self and Other,” I think it would be useful to try to reteach kids how to recognize and respond to emotions. How can you tell if someone is angry at you? What should you look for?

What would you advise adults to do if they notice a child being hypersensitive to what they perceive as anger?

If I noticed an unusual emotional response in a child, I might consider talking through the situation. Let’s say a child is running out into the street and I yell. Afterwards, the child not only looks scared, but it looks like they think I’m angry. I might say out loud: “I bet that was kind of scary when I yelled. I was nervous when I saw you running toward the street because so many cars are in the street. I really wanted to get your attention quickly. Sometimes when people are nervous they raise their voices and yell. I wasn’t angry. I just didn’t want you to get hurt, so I yelled.” If the child has a hypothesis that whenever an adult yells, they are going to get hit, I give them this other scenario to consider.

Other adults can influence kids just by making it explicit. Because we don’t really know how children are reasoning about the causes of behavior. You never can tell what children are thinking. In “Kramer vs. Kramer” the little kid assumed that his mother had left because he hadn’t cleaned his room, so he says to Dustin Hoffman, “Did Mommy leave because she was mad at me?” But of course that had no bearing on why the mom left. In the child’s mind it did.

How do you think society should deal with child abuse?

What society needs to do is intervene. Don’t wait for children to develop problems; prevent problems in the lives of children who are at risk.

You’ve said that not many people study child abuse. Why is that?

One crisis in this country is that very, very few people with doctoral degrees are going into research into child mental health. There are two reasons for that. Number one, people who go into child clinical psychology rather than research have personalities where working directly with children might be much more satisfying than writing grant applications, designing experiments, teaching, running a research lab.

The other thing is, it might be the case that university environments are not a particularly good match for people who work with children. For example, universities say, “We require that our professors publish a ton of research.” Yet, it’s incredibly slow and difficult to work with children. They’re only available after school. You’re dependent on parents bringing them in. A lot of kids who do come in can’t do a task. So scientific research with clinical populations of children takes a lot of time — and patience.

So why are you studying child abuse?

I had originally decided to go to grad school in anthropology to study rationality and relativism — how different cultures decide what’s normal and abnormal behavior. At the last minute I started having nightmares that I was in an office, filled with books, that had no doors or windows. I needed to be more hands-on. And perhaps psychology was a more comfortable level of analysis for me than cultures.

It was in grad school that I became interested in how behavior emerges, where it comes from, and studying children. Then I was planning to be a therapist. But I felt like there were so many children with mental health problems that seeing just a couple of patients was trying to dry an ocean with Kleenex. I thought maybe if I ended up as a professor, I could affect the lives of more children.

It’s got to be hard to construct simple science models of complex human behavior.

This is a big tension in psychology. Human behavior is very complex, very multi-determined. And so one approach is to try to study people in their natural environment. You’re measuring people behaving in the way they really behave and measuring people with whom they usually interact. The difficulty is that you lose experimental control, meaning that in that naturalistic environment, all sorts of things are going on that you can’t measure that make or cause or are underlying the behavior.

You can bring people into the laboratory and make it very similar for everyone. Everyone is alone in the room. Everyone is sitting three feet in front of the computer. It’s four in the afternoon. There’s a snack beforehand. You gain experimental control, but what you lose is that people are then in this very odd environment.

How do you balance biology and psychology?

In order to understand what’s going on in kids’ heads, we also have to understand what kids’ heads are in. We can’t just go one way or another. We want to understand the brain, and we now have the techniques to understand more about the brain. But if we try to make everything just about neuroscience, and we don’t also try to connect that with the experience that people have and the things that happen to them and people they interact with, things they say and hear and feel, then we’re not ever really going to understand human behavior.

So the tricky part is: How do you make the connection? How do you connect people’s experiences and the underlying biology?

Our thinking about mental illness has gone through different phases of evolution. In the 1800s scientists thought that the basis of mental illness was based in the brain. Then in the 1900s psychoanalysis and more humanistic approaches to mental illness came into vogue. Then in the 1970s, with the advent of new drugs and brain imaging techniques, biology came back to psychology.

How do you reconcile free will with everything you’re learning about people?

You know, this issue always bums out my undergraduate students. We all want to be students of human nature because, well, humans are so damn interesting and cool. We also cling tenaciously to our notions of free will. I mean, how can we hold people morally culpable, or punish people, if we cannot hold them responsible for their actions? But here’s the kicker: If humans act based upon free will, then we can’t have experimental psychology. I can’t do an experiment if it’s the case that people decide how fast they will press the lever, or how much brain activity they will expend. Psychology takes as a basic premise a mechanistic, deterministic view of human nature.

It doesn’t mean that we don’t make choices and aren’t free thinking. But it isn’t all free all the time.