It's unusual for a book to come into its own 27 years and three editions after it was first published, but then David Thomson's "A Biographical Dictionary of Film" is no ordinary reference work. It is, as he puts it, "personal, opinionated, unfair, capricious," but since the dictionary first appeared in 1975, readers have also found it addictive and unforgettable. The "Biographical Dictionary" is really a collection of essays on the various people who have made movies both the signature art form of our time and a trashy good time in the dark. And it's also an autobiography of sorts, a wide-reaching account of Thomson's filmgoing life, a fierce argument about popular art and an ongoing investigation of what it means to be human in a world full of spectators and performers.

Plus, the guy can write. Devotees have been known to joke about Thomson's idiosyncratic passions (he says Angie Dickinson is his favorite actress and calls Cary Grant "the best and most important actor in the history of the cinema") and obsessively quote their favorites among his many sterling lines. (Mine: Charlie Chaplin's "a character based on the belief that there are 'little people.' Whereas art should insist that all people are the same size.") His willingness to take liberties with the reference form makes each entry a potential surprise and delight. (Thomson, who has written biographies of Orson Welles and David O. Selznick, took this impulse even further with his 1985 novel, "Suspects," another cult favorite -- though not, regrettably, still in print -- a biographical dictionary of classic fictional film characters whose lives intersect in mysterious and ominous ways.)

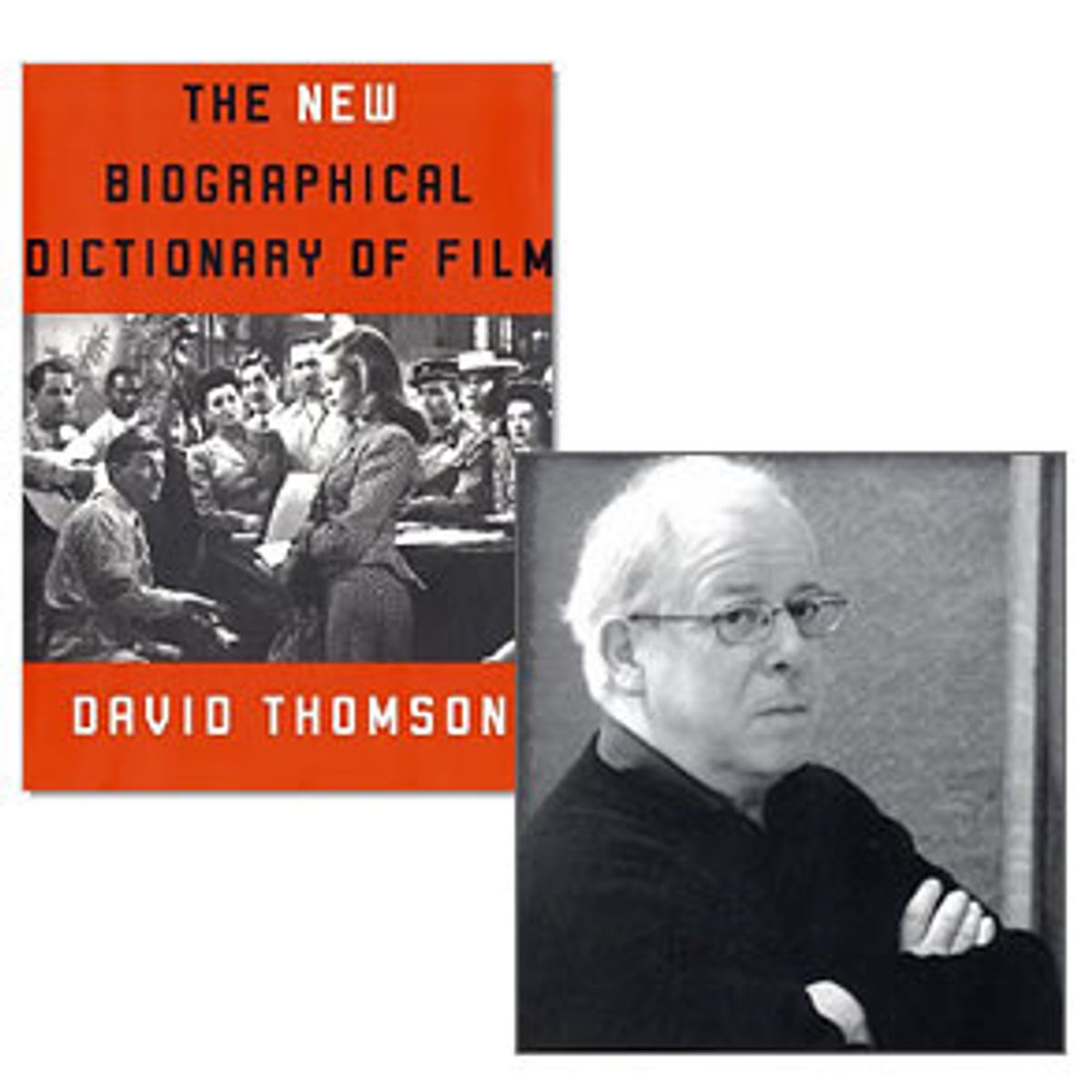

Just out in its fourth edition, and retitled "The New Biographical Dictionary of Film," Thomson's ongoing magnum opus is selling briskly and being widely reviewed -- his audience has finally reached critical mass. A frequent contributor to Salon, Thomson dropped by our New York office to talk about who's in the book, who's out and what makes a movie star different from ordinary mortals.

This is the fourth edition of the "Biographical Dictionary" since you first wrote it in 1975. How much has changed since the third edition?

There are 300 brand-new entries, and every entry has been updated, in the case of the people who are still working. And there's a certain amount of looking back at earlier entries and playing around with a sentence or even changing your mind about a couple of paragraphs. Every time I do an update, there's been room for that kind of rewriting. There are a lot of changes. The brand-new entries are not all new people. Some are people who've been dead a long time and could've been in the book ages ago, like Graham Greene or Rin Tin Tin.

Who gets an entry and who doesn't is more or less determined by how interested you are in them, isn't it?

You're completely correct. It's personal, opinionated, unfair, capricious, sometimes momentary. Sometimes you decide to do someone today for a reason you don't know, and it's a great day for doing that person and you find out you have more to say about them than you ever dreamed, so you say it. [When updating the book] I don't go through the entries alphabetically or systematically. I'm not very good at systematic things. The nearest I have to a rule when I'm doing the writing is that I pick one person I really want to do, am excited to do and one person I've been putting off because they bore me.

Did you find yourself surprised by some of the changes in how you saw or evaluated certain artists -- or figures, because not everyone in this book is technically an artist?

Yes, actually. I decided I wanted to do Pauline Kael. I didn't want to write about her while she was still alive because I knew I had some things to say that were tough and I felt very badly for her. She suffered a terrible fate, that she lost the ability to write when really that is what had been her life.

Because she was very ill.

And because her illness was peculiarly hostile to the act of writing. But she was dead, and I felt now's a good time. I wanted to say what I felt about her as a person because I felt that it affected her criticism as well as the way she conducted herself, but I found I liked her more than I had thought. Yeah, she could be a bit of bitch, or whatever you want to call it, and a lot of people suffered because of her a little bit if they were film critics -- unless they toed the line. But now she's gone, and that's going to fade. I'm not really complaining. I still read her work and I still think she's amazing. So it turned out a much warmer entry than I imagined it would be in advance.

That does happen, particularly with dead people where you've had a chance to reassess everything about them. Even people about whom I have very mixed feelings, like Scorsese, I think if he were to die tomorrow -- and I'm not urging that because it would be horrible for him to die before "Gangs of New York" opens -- immediately everything gets readjusted. You say, Well, even if some of the later films were not so good, some of the earlier ones were amazing and they changed everything. That balance comes into play.

I take the view that in the end a person only needs to write one great book or make one great film. They can write 10 terrible books and we regret and lament that and we may have to explain it. But if there's one great book or one great film, then they've got to always be remembered. It's up to people like me, who are following behind the procession of cinema, to say, "That's someone to remember." It's easier, you see it more clearly, when they're dead.

You're including more people who work behind the scenes: makeup artists, agents, etc.

There's quite an important entry this time on Edith Head, who was the great costume designer in films and very influential on the way women dressed, not just in how films looked. I've become more and more interested in those people. I'd love to write about a movie publicist someday. They're very important, and outrageous often, and funny. They do a very important job, which academics might like to think doesn't exist and isn't part of film, but anyone close to the industry knows that it is. To put a publicist in would be a very good corrective. You're quite right. I'm looking further afield.

What prompted that change?

I've made a journey. This book began when I was only English and was originally written in England. Now I've lived in California for 20 years, and I've been on the edges of filmmaking quite a lot, and you just learn something that you don't want to think of when you're younger and hero-worshipping the people who make films. You put all the credit, then, on the directors. You realize as time goes by that film is full of collaborations, full of compromise, full of cheating. Frequently people whose names aren't even on the films have a lot to do with them, and in general I'm trying to make note of that a bit more. People who do what are called "craft" things on a film, as if creativity and craft are different, which I don't think they always are. I'm putting more of them in, and if there's another edition I think I'd push it further still.

I also have a notion -- I didn't do it this time, but I came very close to it -- of putting my son in the book. He's 13. I see a lot of films with him. He's had an effect on the way I see films. The people we see movies with -- and in the course of our life that can be quite a lot of people who we've often gone to the movies with and sometimes one or two who almost all our lives we've gone to the movies with -- those people can have a very important influence on what you think of movies. They can change your attitude. So I would be interested to put an entry or two in that would refer to that.

In the way the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier stands for all soldiers, it would be the entry for the Unknown Companion.

Absolutely. It's a situation that a lot of people have been through. Particularly when you're a teenager: You take someone of the opposite sex to the movies and it's a date. And then you find the movies more interesting than the date. But the movies are for many, many people a romantic event. You hear of married couples treasuring their date night, when they go to see a movie.

How does your son see films differently from you?

I could talk a lot about this, and I have to be careful not to assume that all kids that age are like my son. He's very interested in the movies, but he does not identify with characters at all. He's not very interested in stories. He's not really someone who goes to the movies for an emotional experience. He goes almost for a neurological experience. He loves the sensation, he loves the spectacle, the special effects. He's fascinated with how they do it. We've had occasions in the movies where he'll turn to me to say, "How do they do that?" and he'll notice that I'm moved by what they did and the question is stillborn, because he has a certain respect for me. In other words, we're going with very different needs, and yet we're very fond of each other and we're quite alike. And I find that fascinating.

When I was a kid, people, kids went to the movies to identify in a fantasy way. I believed the stories were very important, very serious. He thinks that the stories in movies are almost always silly. For him, the movies have become more a camp form. He thinks the movies do ridiculous things. For example, whatever you think of the film, "Saving Private Ryan" moved me. He was of the opinion that sending that many men after Ryan was lunatic. No commander should have done it. He believed it was a film about explosions -- not an unsophisticated critical attitude; many films are about explosions. I got really caught up with the Hanks and Sizemore characters particularly. He didn't care about them. He thought they were ciphers. We both hated the ending, that framing device, but we were on very different tracks with that film.

Here's another: We went to see "The Matrix," which is one of his favorite films. I grappled with it as best I could, and after about half an hour I turned to him and said, "Tell me, can you make head or tail of this?" I mean, just in narrative terms. He hissed back, "It doesn't matter!" He wasn't just telling me to shut up, to stop intruding. It did not matter for him. It was imagery. And actually that helped me with the film. I tried to just watch it as a moving canvas and it became more beautiful. There's an interaction, and he may get something from what I'm suggesting, but I'm getting something from what he's suggesting for sure.

When you do a book like the "Biographical Dictionary," you get a lot of feedback from the general public about what you included or left out and also your take on things. Over the years that you've worked on this book, what are some of the most notable or recurring things people have said to you about those decisions?

Last night I was giving a talk about the book to a very friendly audience and there was one gentleman who made it very clear that he was a big fan of the book. But he said that he was actually offended by the entry that appeared for the first time in the third edition, about Johnny Carson. Johnny Carson seemed to him to be a person from a completely different world. I said that I understand that and tried to explain that Carson is in the book because when I came to America -- very eager, greedy to learn about America -- I watched a lot of television and Carson struck me as a man who was so expressive of certain American male attitudes.

There's also the fact that when Carson was on TV and in his prime, he was on for a number of hours per year that was the equivalent of 50 or 60 films. People on television, sometimes, we know awful well. And including him was a kind of gesture, to say, "Don't forget, there's a whole lot of TV people who we watch on screen, and often on film, too, who aren't in this book." And maybe they could be. Maybe this book should be a biographical dictionary of the screen or of screen people. Because maybe that's the crucial thing. The screen is the invention, more than film or tape. A few people have remarked on the Carson thing. Film purists find it jarring.

There are always people left out. This time there are some Asian and Iranian filmmakers, with great claims to be in the book, who are not there. I'd have to say that reflects the fact that I've not seen enough of their films. I have to be honest about this book. But whenever you end it -- and you know this because you did a reference book -- you leave people out, and you've got to live with it.

It's always surprising what people zero in on, though. You think, I've got to cut so-and-so, but I'll never hear the end of it, and then nobody makes a peep. Instead they're on your case for not including someone you didn't seriously consider.

A couple of young people have looked at the book and said, "Adam Sandler's not in it." That's a good point. Adam Sandler doesn't interest me, so he's not in the book. But he's important, so maybe I should have said, "Why doesn't he interest me?" and written about that. Whenever people complain about an omission, they've got a point.

On the whole now, though, people have learned -- and accepted or not -- that it's a book to be read. The idea that it's a reference book is a bit of a trick. It's a book to be read, to make you begin to argue. It's meant to be provocative and to encourage some kind of critical conversation, in your head and with your imagined version of me. What's nice about going to a bookstore and meeting people is that you get into that conversation for real.

Do you have a favorite new entry?

The one I worked hardest over was the Graham Greene one. It's not that I like Greene, but he's meant a lot to me in my lifetime and I take that very seriously. But I think the one I felt the best about was the Hoagy Carmichael entry. Did you know, by the way -- I only heard this recently -- Ian Fleming believed that Hoagy Carmichael should have played James Bond?

That's unimaginable. He's too short, and there's never been anyone more Midwestern than Hoagy Carmichael.

Totally, totally! Makes Ian Fleming sound even stranger still. A very strange man.

Do readers have a favorite entry?

One of the entries that gets most persistently brought up in a teasing but fond way is the entry on Angie Dickinson. As long ago as the first edition, I wrote that I could even stop the book there because she's my favorite actress. I love her -- I've never met her -- I truly love her. Whether she's my favorite actress, well, that's a silly concept. I said it to provoke, and I said it because she was probably the most far-fetched of my favorite actresses. If I were to list all of my favorite actresses, she'd be the one -- either her or Tuesday Weld -- that would raise the most eyebrows, because Angie Dickinson and Tuesday Weld are not thought of as great actresses in the Dame Edith Evans category. So, it would get an argument going. And I adore her.

One of my favorite entries is the James Dean one because it includes a description of you seeing him on-screen for the first time, and what the theater was like, an old-fashioned movie palace.

That one's had a lot of attention, too. From the very beginning I knew I didn't want every entry to begin "So and so was born and etc." I knew that as often as I could I wanted to get a very personal opening, that started an unexpected line of thought or argument about a person. A few of the entries do begin with a first encounter with someone. Dean was very special because by the time I saw my first James Dean film, he was dead already.

So he was already tragic before you first saw him?

Absolutely. That makes a big difference. The cult had begun and when you went to see a James Dean film in England you knew that you were going to an extended funeral.

With a movie actor, there's such an interesting interaction between the performances on-screen and our idea of who this person is in real life. Dean is a classic example. In some ways, his screen performances and his actual self seem close because of the kind of actor he was, but above and beyond certain performances there's an idea of who a star is that seems very particular to the movies.

Absolutely, and yet it is more than the movies, too. It's clear that this legendary image that many people on-screen have in their own lifetime -- they didn't have to be dead to have this mythic quality -- which was not the same as their real nature, it's quite clear that this has carried on now into things like politics and celebrity as a whole. Celebrity is a child of the movies, certainly a child of photography. We're tickled and intrigued by the way even nonentities -- I would say seriously uninteresting people -- like Reagan or Madonna, can exert an extraordinary appeal on the imagination. And in many cases, certainly Reagan's, I don't think it was a thing he understood or could control. It happens. The first time that split response to an image, a face, the sound of a voice, occurred was in the movies. I think it's one of the ways the movies have shaped modern life in quite remarkable ways. It's a very complicated issued, and it isn't a thing I understand.

There's that very strange experience of knowing someone who then attains a certain level of celebrity, and suddenly there are all these people who have never met your friend but feel they know a lot about them. And often what they think they know about that person is completely different from what your experience of your friend is. And you cannot convince them that it might be otherwise.

Isn't it just? For instance, I don't regard myself as a celebrity but I have a public life, and my wife tells wonderful stories about the stupid things people will say when they come up to me. That's one thing spouses pick up on. They'll say, "You don't know what he's like in real life!" That stuff is fascinating and it's creeping into daily life more and more.

Is that one of the things that makes a movie star, an above-average ability to construct an aura like that?

Yes, absolutely. It's two main things, and you can make them sound technical, but they're magical as much. One, and it sounds simple but it's complicated, is allowing yourself to be photographed. Most people, and I'm one, don't like to have their photograph taken. You flinch, you tense up. You think, Oh, god, go ahead, all right take my picture. You don't want to have it done. You know you're not good at it, not natural at it.

Some people love it. They're natural at it. It's as if they love it because they know the camera is going to see them in ways that real people don't. They're good at letting it come into them, and then they're good at projecting, at reaching out and looking into the darkness and saying, "I'm going to think something when I look out there and millions of people are going to think that I understand them." Now, it may not be as cold-blooded as that, but that's what it comes to. A star is someone whose look in a close-up, looking off at nothing, persuades you, me and millions of other people, "He understands me."

Who do you think is an exemplar of that? Marilyn Monroe?

I don't think she had it. She was not that good at being photographed on moving film. She was good at being photographed in stills. She's something else. Oh, a lot of people have had it. James Stewart had it. Cary Grant had it. Robert Mitchum. Carole Lombard, Katharine Hepburn. Lauren Bacall had it in two films, but then it went. In "To Have and Have Not" and "The Big Sleep," she looks like the greatest thing ever put in front of a camera. She gets dull after that.

People around today ... I think Tom Cruise has it. I would never accuse Tom Cruise of being a good actor, but I think he likes being photographed. They don't have to be beautiful.

Tom Hanks?

He doesn't quite have it in the same way.

It's so subjective. We're talking about our own personal reactions.

It is. And sometimes it comes and goes. Look at Brando's career. When he was very young, Brando had it. It went, maybe because Brando hated it himself and it just frittered away. And now he won't really make films. Some people have it all their lives. I think you could argue that Katharine Hepburn, Spencer Tracy always had it. Cagney had it.

In your entry on Fred Astaire you talk about how difficult it is for someone to move well on film. That's not the sort of thing the average filmgoer notices, or at least not in a conscious way.

Walking -- I wasn't talking about dancing with Astaire. I wrote about this in Salon, that while watching "Ocean's 11" I finally noticed that Julia Roberts is an awkward walker. She had to walk across some casino floors several times, and I noticed that she's shy about walking. And a lot of women are -- a lot of men are -- particularly if they think they're being looked at. But walking across space is a big thing in movies. It's a big part of what they are. Some people can do it effortlessly and gracefully and you love what you see. A film like "The Big Sleep" is full of shots of Bogart just walking across rooms in a full-figure shot. It's as if Howard Hawks, the director, had just seen that the more Bogart did this the more people appreciate him and like him because he does it so damn well.

And isn't that a key part of the director's role, to draw that out? To recognize it and capitalize on it or teach somebody how to do it if possible?

A big part of it. It's seeing. You can't make a film with someone unless you've looked at them in a way that's intense and maybe embarrassing. That's one of the reasons why people making films so often fall in love, because the look that's required is so like the look of developing affection and seduction. For instance, Garbo was fantastic in close-ups. Not so good in full-figure shots. She was a little lumpy; she didn't have the greatest body. You've got to learn that, you've got to see what people can do. Obviously, some actors can do it all, but not all of them.

It's very interesting when you trace careers to see when the awareness of that inner personality comes into being. Bogart, for instance, began his career as a villain. And he was really a very routine villain. He could do it, but no better than 10 other people at Warner Bros. at that time. And then gradually in the '40s someone got the idea that if you took Bogart's toughness and nastiness and you made a new kind of hero -- a loner, cynical guy that you're not going to win over easily, the sort of character in "Casablanca" -- he suddenly looked magical. That's when Bogart's stardom begins, after a full decade of supporting parts.

This is reminding me of conversations that I've had recently about classic films -- I think I was talking about Hoagy Carmichael, who I was so happy to see getting an entry in this new edition. I said, "He's the piano player in 'To Have and Have Not,'" and I was surprised to learn that so many people hadn't seen that movie. You can't really get through an American high school -- or certainly college -- without reading "The Great Gatsby," but you can easily do it without ever seeing a Howard Hawks movie, when he could easily be called the Fitzgerald of American movies.

This is true now. It wasn't true in the '60s and '70s. There was a tremendous burst of film activity then in higher education in America. That's when most of the film programs and departments started. People rushed into those classes and loved to look at the old movies and they became film buffs. I think the term "film buffs" comes from that era. It's changed again. You're quite right. Students today have suddenly gone back to zero and they've seen nothing. Which is sad in a way, and makes us all less film-literate, but from my point of view, it means that the book has a greater value! But you're quite right, the classics of American film are, I fear, fading away.

Not to mention classic foreign films.

I was at a so-called sophisticated dinner party last night and we went around the table and only one person in a group of eight, apart from me, had seen a Jean Renoir film. Now, 20 years ago, that wouldn't have been the case. He was well-known. And I don't know that it can ever be properly regained.

On the upside, are you pleased with the emergence of the DVD? I've found that I've learned so much about filmmaking from them through watching the extras and listening to the audio commentary, especially when it's done by someone other than the director -- from photographers and editors, for example. DVDs have hugely increased my appreciation of all the different kinds of people who work on films and what they do.

I think the DVD is amazing. What a godsend to film education and appreciation. It teaches you so much about how things are done, and that helps you enjoy it more. The only thing is that I remember an age when going to the movies meant going into a great palace, overly decorated often, sitting with a mob of strangers, feeling you were trapped in there, in the dark, watching an image as big as a house. Sometimes a face was a big as a house, and it needed to be because it was that emotional. That's a harder experience to regain. The screen has become smaller. It's become much more useful, much more manageable, but there is a risk of the emotional charge being reduced.

I think if you're teaching a class in film, you've got to use DVD. It's so classroom friendly. If the kids want to go away and do analysis of films, DVD is made for that. You can stop and start it. It's perfect. But at some point, and I think early, those kids should see that film under the ideal form, because visually it's different. Space means something else when it's as extensive as it is in a theater. The light is different when projected than when bouncing back to you from the cathode tube. The DVD has changed the life of every film buff, but I hope that the big image will never be lost.

Shares