Want to hear what people will say about you when you're dead? Just commit a felony. There's no quicker or easier way to get all your high-profile colleagues to paint your creative career in the glowing terms that it deserves.

Unlike obituaries, which can seem downright cruel in their exultant prose after the fact, post-crime reaction pieces afford the celebrity a breathtaking glimpse at his own immortality.

But will friends and colleagues get into the specifics of your successes, giving you credit for everything from toppling the Berlin Wall to making curly fries widely available in the Third World? Or will they ramble on about your recent sobriety and relative emotional stability in ways that cast a harsh light on your checkered past as a gun-totin', substance-abusin' loner?

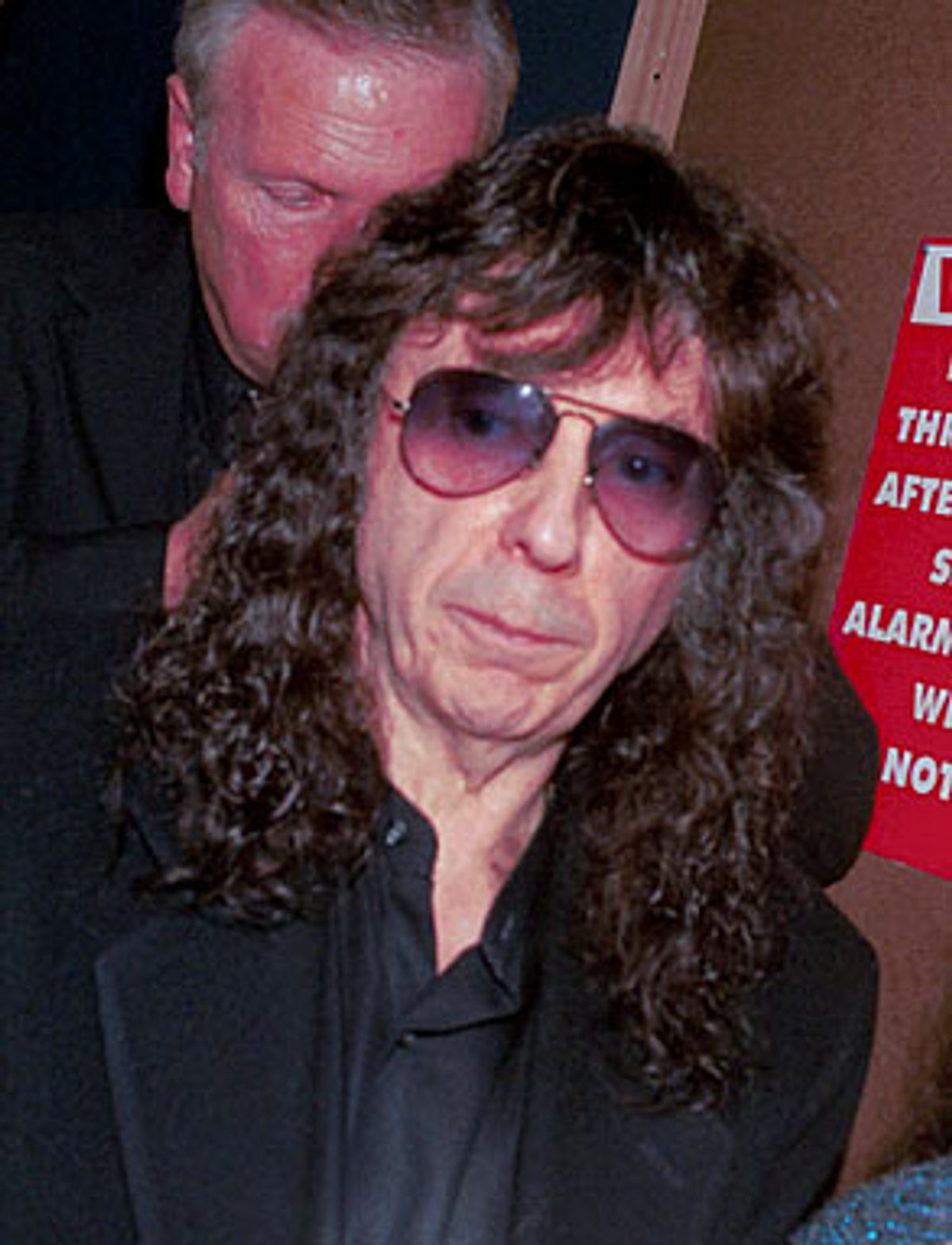

If, like Phil Spector, for several decades now you've enjoyed the freedom afforded by massive wealth and celebrity to lose your doughnuts, they'll do both.

In an article written just after Spector was arrested Monday morning for the suspected murder of actress Lana Clarkson, found dead in the foyer of his Los Angeles-area mansion, the L.A. Times gushed that Spector's "music was infused with a shimmering magic and an orchestral bombast that made it jump out of the radio." In the same article, Robbie Robertson claimed that Spector's unique sound "changed Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys' lives in terms of how to make records. It changed the Beatles' lives."

MTV's Kurt Loder took such praise a step further, stating that no one "has changed the sound of popular music as much as Phil Spector did" and calling him "one of the great creators of rock 'n' roll music."

But such high praise inevitably foreshadows the coming storm. Loder also described Spector as "an increasingly odd and isolated character." Elsewhere, the anecdotes of odd or creepy behavior were emerging: the observed psychological disorders, the alleged brandishing of firearms during sessions with the Ramones and John Lennon, the name-calling, the countless nanny-nanny boo-boos, gathering dust for years, waiting for just such a glorious I-told-you-so moment. "I never met anybody [else] like him and I hope I never do," Dee Dee Ramone once said of Spector. Reuters pronounced him "The Orson Welles of Rock." Spector himself told London's Daily Telegraph, "I have a bipolar personality ... I am my own worst enemy."

But the really damaging stories always come from the exes -- even if they have to be dredged up from 20-year-old documentaries. According to Loder, ex-wife Veronica Bennett suggested in a 1983 Channel 4 documentary that Spector's behavior may have been influenced by his press: "I think Phil was a very normal person at the beginning of his career. But as time went on, they started writing about him being a genius. And he said, 'Yeah, I am a genius.' And then they would say, 'He's the mad genius.' And so he became the mad genius."

With such a muddled mess of opinions floating around, it's easy to forget that this is only the beginning of the media dog-pile. Once new evidence arises, or, if Spector is found guilty, an even darker picture should emerge. Celebrities like Robert Blake and O.J. Simpson have demonstrated that, once that verdict comes in (or even beforehand), friends will start to recall a darker, uglier you than ever before.

But, paradoxically, if you're actually convicted, things should start looking up: You'll have the benefit of looking all sallow and depressed in your prison garb. When people think you're accustomed to savoring fine foods and sleeping on Egyptian cotton sheets, they seem to have a tough time seeing you suffer through poly blends and mystery meat stroganoff. Thousands of hearts will cry out to you, and worry about how you're sleeping at night and whether you'll have to trade your cup of tapioca for the right to remain unmolested by T-Bone, your cellmate. Those thousands of hearts have watched "Oz" -- they know the deal.

Your time behind bars might ruin your complexion, but it'll do wonders for your image. Think Barbara Walters interviews, Internet chats, grass-roots movements to set you free, featuring visits from Susan Sarandon and T-shirts with your face on them. You might even land a regular spot on "Ally McBeal" -- or, uh, "Boston Public." Still.

But if you're proved innocent -- or just not proved guilty -- the big house will seem like a stroll in sheep's meadow. When your lawyer (Johnnie Cochran or Robert Shapiro, take your pick) announces that "justice has prevailed," your status will suffer immensely and immediately. You won't be invited anywhere anymore. You'll be forced to move to South Florida, the only place in the country that's celebrity-hungry enough to overlook alleged criminal activity. You'll have to make new friends O.J.-style, by hanging out at the local Roasters 'N Toasters at the mall.

Spector may think he's in a river of shit deep and under a mountain of trouble high, but in truth, he should enjoy that quick fix of widespread glory while he can. After all, it's a fix heretofore unavailable without sinking to the bottom of a swimming pool or cascading through a tunnel at 120 miles an hour.

Come to think of it, celebrity crime stats might drop significantly if the media made it easier for big names to read magnificent praise of their life's work without their having to die or become incarcerated. Sure, there are always fan Web sites, but when your following is smaller than SpongeBob's, the satisfaction of such sites is limited.

Why should felonists be able to bask in their own glory, while law-abiding legends miss all the fanfare? Imagine if the New York Times had faxed Frank Sinatra a copy of his obit, the one that was surely assigned and edited months before his legendary blue eyes gazed out across those acres of waxed floors at Cedars-Sinai for the last time. Frank probably spent the last few weeks of his life watching "Friends" reruns when he could've been reading his own press, the most glowing press yet in a lifetime of glowing press.

But the tragedy of Phil Spector is that he seemed unable to enjoy any of it. When you get beyond the cheap amusement of another media circus, the sad facts remain: Lana Clarkson, by all reports an extremely kind and optimistic person, died unnecessarily, and Spector personifies the ultimate emptiness of even a lifetime of the most exalted praise, when you lack the ability to feel it. As he told the Daily Telegraph, "Those records, when I was making them, they were the greatest love of my life. I lived for those records. That's why I never had relationships with anybody that could last ... That's why I can't figure out why they have so little significance for me today."

Shares