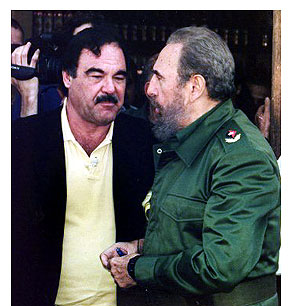

On the red carpet at the Jan. 18 premiere of his Fidel Castro documentary “Comandante,” Oliver Stone struts before the entertainment TV cameras at the Sundance Film Festival. He has the luxury of knowing that probably nothing he says will ever be broadcast. Outshone by the likes of J.Lo and Britney at the festival, his documentary, which doesn’t air on HBO until May, won’t garner much press here.

So he seems particularly relaxed, and the TV reporters, more used to probing the complex mind of Ashton Kutcher, lob Stone softball questions about what will no doubt prove to be a controversial film, seemingly unbeknownst to most of them.

What did you think of Fidel? he’s asked.

“I thought he was warm and bright,” Stone says. “He’s a very driven man, a very moral man. He’s very concerned about his country. He’s selfless in that way.”

The perma-tanned reporter smiles approvingly. Stone goes on; his movie will allow viewers to “see behind the mirror, behind the curtain. You see the man with the beard and the cigar, and he’s not quite what you think he is.” The film “doesn’t make judgments,” he allows, and Castro is “obviously on his best behavior. But he lets you see.”

For Stone, the chasm between Castro’s best behavior and his worst doesn’t seem that wide. Edited down from 30 hours of footage shot over three days in February 2002, the 90-minute “Comandante” is interesting in its unique behind-the-scenes footage of one of the world’s most ruthless dictators. And if you didn’t know anything about Castro, you might enjoy the heroic portrait Stone paints of the revolutionary leader, and the familiar banter between them. “I think we treated each other as equals,” Stone says at Sundance, “which was good for the camera.”

But it’s not so good for the truth, and the resulting film is enraging.

“I know people are very political, and he’s a polarizing figure,” Stone offers at Sundance. “But I’m really after the man behind the polarizing.”

The reasons behind Castro’s polarization are pretty clear. Having seized power in a bloody coup in 1959, Castro’s tyrannical reign is one of the few matters upon which both the left-leaning human rights organizations and right-leaning leftover Cold Warriors can agree. Cuba has no freedom of speech, of the press, or of assembly. No right to vote. Dissidents and journalists are beaten and detained. In prison they are often starved, denied medical care, and “re-educated.” Abject poverty has forced many Cubans, including very young girls, into prostitution. Moreover, boats packed with Cubans trying to flee these conditions have been deliberately sunk by the Cuban government, killing their passengers. In his film, Stone touches on almost none of this.

Of course, when it comes to exclusive interviews, it’s not uncommon for reporters to engage in some sort of barter — whether you’re Bob Woodward or Mary Hart — that trades access for criticality. And yet, when Castro tells Stone, “I assure you that in 43 years of revolution we’ve never practiced torture. Believe us or not,” the silent, unquestioning Stone leaves us with the impression that he believes him — and thinks we should, too.

There are many other moments when Stone plays the quiet American, and anyone with a passing knowledge of history is left only to groan silently in the theater.

Stone does insert a couple of winking contradictions in the editing room. After Castro declares that there is “no more discrimination” against gays, Stone cuts to a shot of a rather flouncy-looking Cuban sitting solo in a restaurant’s “Area de Flores,” the gay-segregated seats. This is hardly the worst of Cuba’s long history of oppressing and arresting gays — in the past, those discovered to be HIV-positive through Cuba’s mandatory testing programs, for instance, were incarcerated and quarantined in “AIDS camps” — but at least it’s a critique.

Likewise, Stone tells Castro that a member of his production team, Carlos Marcovich, witnessed the government’s practice of having an informant on every block.

“That was his imagination,” Castro says, and Marcovich rolls his eyes at the camera. But Stone’s follow-up question is preposterously naive. “Can’t you simplify the system so these guys don’t get rewarded?” he asks Castro of the informants. From the question, Stone seems to think that the informants are just an unfortunate cottage industry that needs to end, rather than an organized part of the Castro’s governing style.

Since Stone surrendered his critical eye, what does he give us instead? To his unctuous interlocutors at Sundance, he played up sex. “I tried to make a little bit of a romantic triangle between Che [Guevara] and Fidel and Evita Perón, believe it or not,” he said. “It’s in the movie because they all in some way or another were devoted to the people’s cause. And that’s what’s beautiful about the movie. And Fidel still maintains that after 50 years, he’s still doing it.”

That Eva Perón was “devoted to the people’s cause” is surely subject to some debate; her charitable activities aside, detractors considered her a fancy propaganda tool for her fascist husband, and together they ruled Argentina vindictively, shutting down newspapers that disagreed with them. But that doesn’t stop Stone from inserting fatuous “Evita” references in “Comandante”; throughout the film violin strains from the Broadway score of “Evita” swell up behind images of Che and Perón and then, ultimately, Castro.

Making Castro sexy becomes a preoccupation in the film. He jokes about smuggling some Viagra in for the 76-year-old tyrant.

“So you want to kill the enemy with a heart attack,” Castro jokes. “You will get the medals you didn’t get in Vietnam.”

Castro is corrected; Stone, in fact, was awarded two medals in Vietnam, he is told. It is intended as a moment of pathos: Castro’s face grows grave, and Stone looks sheepish and a bit disturbed, as if his Nam demons have come back to haunt him.

Castro — who sent soldiers to Vietnam to help the Viet Cong — then praises his fellow soldier. “It gives you the courage to do what you’re doing now,” Castro says.

It’s a completely self-congratulatory scene, and it tells us about a quarter as much about Castro as it does about the gap-toothed filmmaker standing before him, who seems beholden to a childlike redemptive faith that even despots like Castro, who pledged to help kill American soldiers — including Stone — can be good people too, if only we let them share their feelings.

That same faith prompts Stone to ask his new friend, “Have you ever wanted to talk to a psychiatrist?”

“It has never crossed my mind,” Castro replies. “And I have never been asked that question from day one, for whatever the reason.”

These are the types of queries that intrigue Stone, and they do lead to some telling, if tritely sentimental, moments where, for instance, Castro expresses regret at not having spent more time with his son, Fidel Jr., and blanches at discussing past lovers. These are not uncommon moments in the life of any powerful man, and they do serve to remind the viewer that Castro is flesh and blood.

But the biggest miscue comes when Castro spins the Cuban missile crisis. Castro claims, with no apparent follow-up questions, that he didn’t have anything to do with the nuclear warheads the Soviets shipped to his shore, ultimately bringing the world to the precipice of Armageddon.

“We did not like the idea of stationing Soviet missiles here,” Castro says. And after the U.S. spy plane noticed the activity, “we thought we’d be obliterated.”

“They put our interests aside,” he says of the USSR, calling them an “erratic” ally. Of course, it’s much easier now for Castro to criticize his Soviet patrons: They no longer exist.

Stone does have the gumption to ask Castro about his Oct. 26, 1962, letter to Nikita Khrushchev, in which Castro suggests that, if Cuba is invaded by the U.S., the USSR might do well to eliminate the United States forever, presumably with nuclear weapons.

In the letter, Castro wrote: “The dangers of their aggressive policy are so great that after such an invasion the Soviet Union must never allow circumstances in which the imperialists could carry out a nuclear first strike against it.” Thus, such an invasion “would be the moment to eliminate this danger forever, in an act of the most legitimate self-defense. However harsh and terrible the solution, there would be no other.”

The point is very clear: Castro was asking the USSR to destroy the United States entirely if it attempted an invasion.

That’s not clear at all in “Comandante.” When Stone asks him about this letter, without going into much detail, Castro first points out that he was merely calling for the nuclear obliteration of the United States if Cuba was invaded. “I did not say attack,” he says, but rather, attack if Cuba was attacked.

Then Castro places blame for the letter on a poor translation due to the inadequate Spanish of the Soviet ambassador to Cuba. It’s nonsense, but Stone doesn’t bring the viewer up to speed on which letter he was talking about, and he doesn’t point out that the actual letter exists, as does its actual, terrifying translation.

Could the world stand a reexamination of Castro? Of course. The United States’ 41-year economic boycott has been as successful in getting rid of Castro as was that JFK-era CIA plan to sneak exploding cigars into his humidor. Many conservatives now consider ending the boycott — long a cause of the left — to be not only practical but also somewhat less hypocritical in light of the United States engagement with perhaps equally oppressive communist China. (When Stone asks him if he’s a dictator, Castro notes that he’s “seen the United States government being friendly with some big dictators.”)

But Stone falls into a dangerous trap of other political critics. They get so angry at U.S. leaders that they seem to instantly give the benefit of the doubt to anyone on the United States’ enemies list.

Stone, of course, has never been one for nuance. There was the bad sergeant vs. good sergeant simplicity of “Platoon,” and Charlie Sheen’s interminable “Who am I?” soliloquy in “Wall Street.” But this isn’t fiction, not even the historical fiction of “JFK.” This is an actual dictator, with a half-century of human rights abuses under his olive greens, and Stone treats him as if he were a Central American Jim Morrison, just another misunderstood artist. (Speaking of the Kennedy assassination, Castro, long theorized to have played a role in the killing himself, tells Stone that “I have never believed the theory of the lone gunman.”)

It’s unclear how well Stone will be able to defend this film. At Sundance, when a Latin-American reporter — clearly slightly better versed on the topic than his American colleagues — prodded him a bit on the sympathetic portrayal, Stone demurred.

“I would rather have the film speak for me,” Stone said. “I’m not a scholar. I don’t know everything he wrote. But I’m pretty tough on him on some questions.”

Castro, apparently, isn’t the only barbaric Third World superstar set to sweat under Stone’s “tough questions.” His documentary on Yasser Arafat, “Persona Non Grata,” will be based on 80 hours of film that Stone recently shot in the West Bank, commissioned by French and Spanish TV. Until the film’s release, we can only guess how Stone treats his subject. But in what was possibly a sneak preview, he recently told Variety he “understands why suicide bombers feel the way they do.”