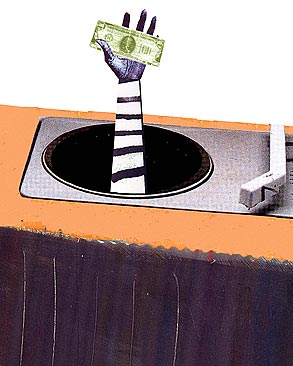

Amid a flurry of topics covered at the Senate Commerce Committee’s recent hearing on radio consolidation and the rise of industry behemoth Clear Channel Communications, one issue in particular seemed to pique the interest of several senators: “pay-for-play.” This refers to what some critics have called a modern-day payola scandal, the murky system by which record companies pay influential independent promoters to get songs on commercial radio.

It seems Congress is sending a bipartisan message about pay-for-play: Clean up the funny business.

After listening to testimony from Eagles lead singer Don Henley, who decried pay-for-play as nothing more than extortion artists and record companies must face in order to have a chance at commercial airplay, conservative Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison, R-Texas, said she was concerned about what “appears to me to be a sophisticated way an artist is required to pay money to be on major stations,” and suggested updating the nation’s payola laws.

Liberal Sen. Russ Feingold, D-Wis., reported, “Artists are very concerned that playlists are no longer based on quality — subjective as that is — but are sold to the highest bidder instead.”

And addressing a broadcast lobbyist who defended radio clients against allegations they illegally profit from the indie payments, Republican Sen. John McCain of Arizona noted, “I’m very interested in your statement that your members do not take cash or gifts in exchange for airplay.” The clear implication was that if McCain found out differently he’d summon the lobbyist back for an explanation.

The next forum to examine pay-for-play could be the Senate Judiciary Committee, which may take up the issue in coming weeks, according to several Beltway observers. “It’s picking up steam in a hurry,” says one Capitol Hill source.

Some broadcasters have gotten the message about the pay-for-play contracts they sign with indies. “I’m going to phase them out and not renew any,” one radio chief tells Salon. Although these agreements are legal and highly profitable for stations, the broadcaster says they’re no longer worth all the controversy they attract.

Nothing would make record companies happier than to see pay-for-play die. Even though the five major music labels essentially created the indie promotion system decades ago, they can longer control it and have been searching for a way out. Now their sights are set on Washington. Working through the Recording Industry Association of America, the major labels are hammering out a petition to file with the Federal Communications Commission, asking that it revisit and update its nearly half-century-old payola laws so they reflect today’s marketplace.

“If Congress were interested in the issue, that would be a welcome addition,” says Cary Sherman, president and general counsel of the RIAA. “And if Congress holding hearings were to spark the interest of the FCC, all the better.”

The irony is that if and when Congress moves to curb indie promotion — and that still remains a big if — the practices it uncovers may be radically reduced from what they were just two years ago. That’s because, thanks to two parts economics and one part courage, the record companies, battered by falling CD sales and vanishing profits, are finally taking control of radio promotion and cutting back on indies.

“Payments are being cut back dramatically and the system is being dissolved,” insists a major label promotion executive who, like many insiders who discuss this sensitive topic, requests anonymity. “We’re not intimidated by them anymore; I think it’s the beginning of the end. If the government closes down the indies, the music industry would be excited because it would save us the exhaustion of doing it ourselves.”

Nobody inside the industry thinks indies will go away completely, because record companies will always need a third party they can turn to in order to help create hits. “It’s a bit naive to think that lobbying or influence peddling will disappear just because the industry’s having financial problems,” notes one longtime independent promoter.

But there’s a fundamental shift underway that radically reduces the money indies take in, and the influence they exert. That’s good news for artists, who end up shouldering roughly half the cost of indie promotion based on their recording contracts. The bad news is that insiders doubt that curtailing indies will do much to loosen playlists or make commercial radio more adventurous.

Musicians are anxious for relief from pay-for-play, but they’re reluctant to address the topic publicly for fear that indies could retaliate by trying to keep the artists’ songs off the radio. Testifying before Congress, Henley spoke on behalf of the Recording Artists Coalition, a lobbying group that represents more than 100 acts, including Offspring, the Dixie Chicks, Beck and Bruce Springsteen. No doubt they’re glad that Henley, who has sold in excess of 50 million albums in his career and doesn’t have to worry about scoring another hit single, is willing to step out publicly on the issue.

For years the pay-for-play system operated in obscurity. No more. It’s been nearly two years since Salon began publishing a lengthy series detailing the controversy building over pay-for-play. The lucrative practice, which helps determine what millions of Americans hear on the radio every day, has been pushed into public view as artists, managers and record companies continue to ask pointed questions (often anonymously) about the economic and cultural implications of pay-for-play. Economic, because the system costs the music industry approximately $150 million each year. And cultural, because pay-for-play effectively shuts off access to commercial FM radio for artists or record companies who can’t or won’t spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to promote just one new single.

The system now known as pay-for-play involves independent promoters who pay radio stations for the exclusive right to act as a kind of middleman between those stations and record labels. Indies usually pay at least $100,000 per station, and as much as $400,000 in major markets. When the deal’s in place, the indie can then send weekly invoices to record companies for every song a station adds to its playlist. This isn’t considered illegal payola under current law, because indies don’t pay stations to play specific songs. Rather, the indies get paid regardless of the songs the station’s management chooses to play.

Every time a song is added to an FM radio playlist, the indie promoter will earn about $800 in a middle-sized market. The take can be $1,000 or more in larger markets, and as much as $3,000 per song for top-rated stations in major cities like New York, Chicago or Los Angeles. Typically, a radio station will add 150 to 200 songs to its playlist every year.

It can cost a label $250,000 just to get a new single played on rock radio. That doesn’t guarantee the song will become a hit. It just gains access to the airwaves. If the song actually does become a mainstream Top-40 hit, indie costs balloon to more than $1 million per song. When consumers complain about the price of an $18 CD, most have no idea how much money record companies spend trying to market those CDs to radio.

The problem for record companies today is that fewer consumers are spending $18 on CDs, or even $13. Thanks in large part to free downloading and file-sharing, CD sales have plummeted nearly 20 percent in just two years, and record companies don’t seem to have a clue how to stop the free-fall.

“We’re in a boat and there’s water coming in,” says one major label source. “The labels have looked at indies and said, ‘You are driving us out of business.’ It’s like the unions and American Airlines. Cutting back on indies has bought us more time.”

With business so bleak, the traditionally free-spending music business has been forced to heed the bottom line. Or be shown the door. Tommy Mottola’s removal as chairman of Sony Music Entertainment last month was widely seen as the price he paid for not being able to stop the fiscal bleeding. Mottola’s division lost at least $150 million last year on sales of $3.5 billion. Sony hired Andy Lack, the former president of NBC News — and a man with no experience in the music business — as its new music honcho.

Radical realignments like that mean the industry’s old business-as-usual approaches are doomed. Says the label executive: “Somebody like Lack comes in at Sony with a completely clean slate, with no relationship with any of these indie guys, and he sees the bottom line for indie promotion and says, ‘What’s this? Cut it.'”

The other reason for the indies’ downfall, besides a collapsing music industry model? Greed. Four years ago, in a pre-Napster world when the industry was flush with cash, indies were firmly entrenched and charging exorbitant fees for doing very little work, according to label executives.

During the ’90s, indies who often represented just a handful of stations began to expand to the point where a couple of larger firms such as Jeff McClusky & Associates, Tri-State and McGathy Promotions had exclusive contracts with hundreds of stations between them. That trend only accelerated during radio’s runaway consolidation following the Telecommunications Act of 1996, when a company like Clear Channel grew from owning 40 stations to 1,225. By signing corporate deals with broadcasters, indies suddenly had exclusive access to a huge swatch of stations, which meant millions of dollars in additional revenue. But by getting so big the indies forgot what their core business was about: personal relationships with individual programmers, and making a difference when it came to determining what songs a station actually put on the air.

“Just because an indie has exclusives with all these stations doesn’t mean he has a relationship with all of them,” says one radio promotion pro. “Indies got too big and lost the personal connection.”

Over time, the labels began to question what, if any, influence their millions in indie payments were buying. Instead of actively selling the songs to station programmers, the indies simply charged labels whenever one of their exclusive stations added a new single. Frustrated artists, managers and label execs began to see the indies as nothing more than expensive toll collectors. Now, with money tight, the labels are demanding results.

“The corporate deals were the downfall,” says one veteran indie, who’s always worked with just a handful of stations. “It’s time to get back to real relationships.”