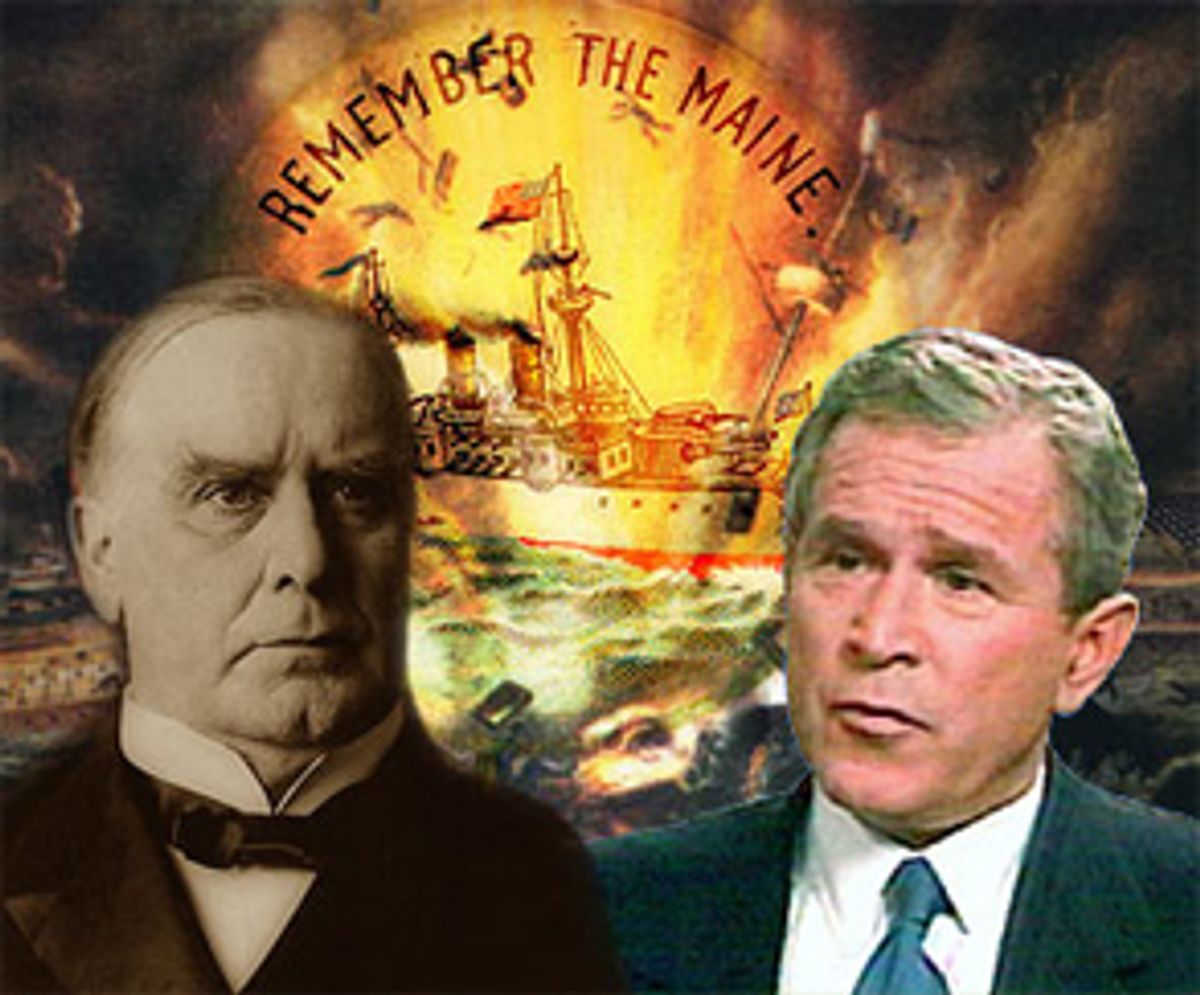

As we head into the inevitable war with Iraq, almost everyone, apropos of Santayana's famous dictum about repeating history, is searching for an analogy. Hawks reference World War II, and cast Saddam as the tin-plate Hitler we must defeat in order to save the world from his aggressive designs. Doves view Iraq as another Vietnam, a quagmire that will result in tragic casualties, both civilian and military, will drain our treasury and bog us down in occupation for years to come. At least as far as the provocation goes, there is, however, a third and possibly more apt analogy. The Iraqi war could be our very own version of the Spanish-American War of 1898 -- the conflict that United States ambassador to England John Hay called "a splendid little war."

Once again we are led by a man whose presidency is adrift. Once again we have a country in deep economic hardship. Once again we have a compliant media that stands to benefit from war. (Ignore the caterwauling about the expense of covering war. War is the very best way to attract an audience and establish your brand.) And once again we have a war that seems to be conceived less in terms of policy than in terms of aesthetics.

The Spanish-America War, like the imminent war in Iraq, had its origins not in any direct threat to American security or in treaty obligations to allies or even in some affront to American honor, but in a desire to project a new sense of the country's power and responsibility -- in historian Frank Friedel's words, "to see the United States function like a great nation." Though the world of the late 19th century was not, like ours, dominated by a single superpower, America possessed an abiding faith in her own moral superiority to every other regnant nation, just as it does today. This was (and is) not entirely without justification. At the time, America was certainly more idealistic than Germany, France, England, Japan or Spain. She believed in the values of democracy and equality even if she didn't always believe in their actual exercise -- Third World nations would need a lot of help -- and she increasingly saw her role as international cop, enforcing what other nations were too craven to enforce.

To this crusading impulse was added a sense of restlessness. In the years just before the Spanish-American War, America was suffering from the most devastating depression in the country's history to that date, and recovery was long in coming. More, with the frontier having been settled in their time, as with the end of the Cold War in ours, there was among Americans little sense of direction or national purpose. William McKinley, an undistinguished governor from Ohio who became the frontman for powerful Republican business interests, was elected to the presidency in 1896 not because he projected any grand vision but because he promoted high tariffs, which were the Republican economic panacea then much as tax cuts are now. Still, a year into McKinley's first term, high tariffs had neither roused national passions nor cured the depression. The nation was rudderless, and Republicans were already predicting electoral defeat.

As Theodore Roosevelt, then assistant secretary of the navy, commented, "This country needs a war."

McKinley, unlike George W. Bush, wasn't exactly the most promising candidate to give them one. Belying his rugged, square-jawed appearance, he was a natural equivocator, a political weathervane, and he was certainly no warmonger. Despite the fact that Spain held dominion over Cuba less than 100 miles from our shores, despite the fact that there had been an ongoing Cuban revolution for more than a decade and with it chaos, despite the fact that there were reports of terrible cruelty and carnage at the hands of the Spanish authorities, and despite the fact that the Spanish had inflicted a series of indignities on America by firing on her ships and even ultimately insulting McKinley himself, the president counseled patience. While warning that he would have to "intervene with force" if the situation in Cuba didn't improve, he pressed Spain for concessions, and Spain, like Saddam, reluctantly consented to most of them as a way of delaying sterner action. Spain even declared an armistice to drag negotiations with America into the Cuban rainy season when a military invasion would have been inadvisable. All of this was enough to convince Europe that America had not yet exhausted every diplomatic option.

Patience, however, ran thin after Feb. 15, 1898, when the battleship Maine exploded in Havana's harbor, where it had been docked in a show of American force, and 260 of its crewmen were killed. This was McKinley's 9/11. Assuming that the Spanish were responsible, jingoes, as hawks were called then, demanded retaliation. Still, McKinley remained reluctant to declare a shooting war. He chose to await the verdict of a naval court of inquiry on the cause of the Maine's explosion, which the Spanish insisted was an accident, not sabotage. The report would be the Spanish-American War equivalent of Colin Powell's U.N. presentation -- conclusive evidence of provocation.

Yet even before the court of inquiry attributed the Maine's sinking to a crude mine -- a conclusion that was later convincingly challenged by a 1976 commission chaired by Adm. Hyman Rickover, who termed the cause "internal" -- the war drums were beating deafeningly. The yellow press then, like the cable news networks today, had a stake in America's going to war: Nothing raised circulation like reports of warfare. Both William Randolph Hearst of the New York Journal and his competitor, Joseph Pulitzer of the New York World, pressed for war, invoking "Remember the Maine" as their call to arms. Every day brought new revelations of Spanish depravity, even if they had to be manufactured by Hearst. Congress was seized by war fever. Among the public, too, war sentiment ran high. "Many people are for war on general principles," one newspaper editorialized in a statement that could just as easily have been written yesterday, "without a well-defined idea of why or wherefore." Eventually, McKinley capitulated, letting the war focus his presidency as the Iraqi War will no doubt focus George W. Bush's.

What the war juggernaut seemed to obscure was that Spanish transgressions were as much an excuse for war as a cause, which may be the strongest similarity between that war and our putative one. As Teddy Roosevelt had said, the country needed a war, both to exercise America's power and to show her idealism, but it didn't need just any war. It needed a clean war, an expeditious war, essentially a war without risk or sacrifice, and it chose the best situation to provide one. It was one of the reasons the country was so eager to fight, even though Spain had attempted to placate her. It was also why Roosevelt himself, resigning his post in the Naval Department and fitting himself out in a handsome new uniform, was so hot to enlist. One jingo said that the war would last anywhere between 15 minutes and 90 days. Seen that way, as a lark, war was irresistible.

The real question then, as now -- the question that no one in the Bush administration dare voice publicly, though one suspects it is voiced often in war counsels -- is not "Why war?" as it is for virtually every other conflict, but "Why not war?" Why not get rid of the irritant of Spain or Saddam Hussein when the upside is so high, politically as well as geopolitically, and the downside seemingly so low? And the real substance of the Bush Doctrine is not preemption -- or we would have already attacked North Korea -- but expediency. The unstated Bush Doctrine is the same one that animated the Spanish-American War: You fight the war that is easy to win -- 15 minutes to 90 days -- which is why Bush, like McKinley, has made no call for national sacrifice. To do so would violate the conditions on which we are now prepared to go to war.

In the end, as much as doves may hate to say it, Bush may be right. Why not go to war? The Cuban portion of the Spanish-American War did last less than 90 days, and it resulted not only in Spain leaving Cuba but in America taking Guam, Puerto Rico and the Philippines and thus asserting her power. But if Spain was quickly vanquished, the Philippine portion of the war dragged on for years as America tried to pacify insurgents there, resulting in 4,000 American dead and hundreds of thousands of Philippine civilian casualties. (Anyone looking for the analogy to Vietnam will find it here.) As the saying goes, watch what you wish for ...

Of course the assumption, in 2003 as in 1898, is that war will be quick and bloodless -- that it won't be hell but a piece of cake. At least, that is what the Bush administration is telling us and that is what many of us want to believe. We are going to war no matter what and no matter why. If that sounds vaguely familiar, it is. We have been here before. It is 1898 all over again.

Shares