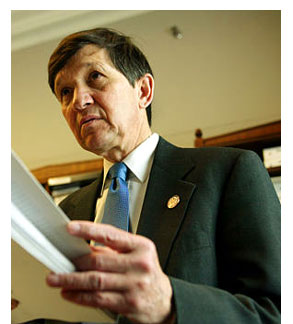

Rep. Dennis Kucinich, D-Ohio, enters the contest for the Democratic presidential nomination with close to no money or name recognition. But he’s been openly, vociferously, against the war with Iraq, and that’s given his long-shot campaign an early infusion of energy — one that has helped him expand his appeal a bit beyond the Common Dreams crowd.

It is not impossible that in the first-caucus state of Iowa — where Kucinich kicked off his campaign and where he hopes to make some inroads — his views will find some real support. For these he will no doubt get some stiff competition from firebrand Howard Dean, the former governor of Vermont, who also supports repealing the 2001 Bush tax cuts and prioritizing health insurance coverage for more Americans, and who opposes the war against Iraq (though in a far more qualified way).

The oldest of seven children, Kucinich first hopped on a national stage in 1977 when, at age 31, he was elected mayor of the city of his birth, Cleveland. It would be a short mayoralty; after Kucinich refused to sell the city’s municipally owned electric system at the urging of the city’s banks, the banks defaulted. In 1979, Kucinich lost his reelection bid. In 1984, he was elected to the Ohio Senate; in 1996 he was elected to the House of Representatives, where he chairs the Congressional Progressive Caucus and is known for being an outspoken and reliably liberal voice on every issue save abortion. He opposes free trade agreements like NAFTA and has spoken in favor of the formation of a Department of Peace.

As his diminutive profile has slowly begun to emerge to the public, certain key issues have arisen that will likely dog him — such as his pro-life positions, and charges of racial political turf fights in his past. But he insists, in an interview, that — his New Age-speak of a “holistic” candidacy aside — he knows what he’s up against.

“I’m not new to this,” Kucinich says. “I did not just fall off the Christmas tree.”

Kucinich spoke with Salon by telephone:

Do you really, truly think you have any chance to win the Democratic presidential nomination?

Yes. Because I’m the only candidate who has a message which encompasses international politics and domestic politics and shows the links between the two. I’m the only one. The only one who has a real economic platform for the United States; it’s fair to say I come from the FDR school of the Democratic Party, which is a full-employment economy, to work for lower interest rates, to cancel NAFTA and the WTO, and return to bilateral trade conditioned on workers rights, human rights, and environmental principles, guaranteed healthcare for everyone, guaranteed Social Security.

A rival’s campaign has brought an April 1972 Cleveland Magazine article to my attention in which you are accused of using racial politics. The story says that after you arrived in the city council in 1967 you began “playing confrontation politics with the city’s black administration as if [you] had invented the game.” Care to comment?

My political career goes back to the ’60s and those were times of vigorous debates. But race was not a factor in those debates. The debates were on issues, not about race — there may have been differences of opinion. But they were never about race. When I was running for mayor I said that half of my major appointments would go to members of the African-American community, and they did. I could cite a long, deep connection with the African-American community. I have a very strong constituency in that community. So in the ’60s was it possible that there were some differences of opinion? Yes. But it was never based on race. Never. Not a chance. Not even the people I clashed with in major ways would ever say that.

You’ve been in the House since January 1997. How many inroads have you made toward your presidential goals?

First let me tell you what I have done. I have been one of the leaders in challenging trade policies and globalization. I’ve organized members of Congress to beat back a couple attempts at passing an extension of NAFTA, though we eventually lost that vote about a year ago. I led the effort to get 114 Democrats to take a position that America’s trade under NAFTA and before the WTO ought to have conditions on human rights, worker rights and environmental principles. A letter we sent to President Clinton on the evening of the WTO talks in Seattle ended up being very influential and turned that discussion on its head for at least a time.

Is there a reason why little of this was actually successful?

We are in a Congress where Republicans have resisted efforts to provide healthcare for all, where Republicans have helped to pass trade laws against the interests of our country.

But let’s say it’s January 2005. How would President Kucinich get any of his agenda passed?

The way to do it is obvious. You run a campaign where the nation becomes so excited with the possibility of change that you bring in a new Congress as well. Look at FDR in 1932 and you’ll see — he brought in close to 100 new Democrats. It gave him a Congress that gave him the ability to get it done.

Your speech to the DNC last Saturday was about the war and about foreign policy.

Successes on domestic policy have been undermined with our move towards war, and they will continue to be undermined. Whether it’s Lawrence Lindsey, the president’s former chief economic advisor, or Professor [William] Nordhaus of Yale, they both talk about the impact of the war on the economy, and they see the cost of the war as anywhere from $99 bil to a trillion or more, depending on the costs of bombing, the costs of occupation, the costs of reconstruction of Iraq. Two hundred billion dollars was Lindsey’s estimate. In addition to that, we all understood that the rising cost of oil would have a very damaging effect on the national economy.

I led the effort in the House of Representatives; I organized 126 Democrats to challenge the administration’s policy. And this is not only about Iraq. The White House relies on preemption and unilateralism, and in this complex world that can only mean more danger to United States.

You’ve had to answer lately some questions about what seems like a shift in your position on abortion, which some have accused you of doing for political expedience, so allow me to ask some as well. In 1996 you ran for Congress as a pro-life candidate —

Wait, wait, wait. When you say I ran as a pro-life candidate, that implies that I ran on that as a campaign theme.

Well, when you first ran for Congress you said that you believed that life begins at conception, and in the past you’ve been pro-life.

I’ve had a five-year voting record, that’s right. Like everything I deal with, I took a lot of time to think about this issue. This is a very complex issue. When I’ve been faced with it for voting purposes, there are a couple things I brought to it. First off, I never favored a constitutional amendment to criminalize abortion or to overturn Roe v. Wade. It’s important to understand that from the beginning.

But there are a whole range of positions that come into this discussion, so in my voting record that you’re talking about, from the second part of the last Congress, it came out that I’ve been giving thought to this issue over the years. There were some issues that came up in the second part of the last Congress that started me to kind of express my concerns about the way the issue was headed.

Specifically you’re referring to a May 2002 amendment by Rep. Loretta Sanchez [D-Calif.], which would have allowed for federal funding of abortions in overseas U.S. military bases. In September 2001 you voted against allowing such funding, but in May 2002 you voted for it.

That was an issue when the woman was paying for it, and the question was as to whether or not that woman was going to have the right to obtain an abortion using her own funds in a military health facility. I voted for the Sanchez amendment to allow women in the military to use their own funds to pay for that.

And despite having a generally pro-life voting record, you support Roe v. Wade?

Yes; I’ve never been for overturning it. In fact, I had an opponent in 1998, Joe Slovenec, who was from Operation Rescue, and one of things he was pressing for in the campaign was a constitutional amendment to overturn Roe v. Wade. And I’ve never been for that.

I know that my voting record indicates very clearly that over a five-year period I have voted in ways that have been supportive of those who have worked to make sure that quality of life is affirmed. And there have been some cases in which those votes can be construed to be part of the polarity that this country’s in. But expanding one’s view is beyond changing one’s mind.

Well, can you explain to me precisely what that view is?

I support a woman’s right to choose, which is guaranteed by the Constitution. And on the other hand, I want to work to create alternatives to abortion. And I think it’s possible to do both. Most Americans would like a leader to be elected who steps out of the polarity and tries to reconcile people and recognize that people may hold viewpoints that seem diametrically opposed.

In 1996 when you won your congressional seat, you declared, “I believe that life begins at conception.” Have you changed your mind on that?

No, no. Not at all. That’s what I think. But we live in a pluralistic society and there are many different spiritual beliefs in this Congress.

If I were a pro-choice Democrat how could I trust you?

I think what I’ve been able to demonstrate to people is they see someone who wants to lead this nation, someone who has the capacity for growth and the ability to look at complex and even divisive issues anew, and that I’ve done that.

Let me ask you about another apparent inconsistency. On “Meet the Press,” in arguing against the war, you argued that the way to remove Saddam Hussein from power “is continue to use sanctions which thwart his efforts to grow.” But in the Progressive magazine last November, you wrote, “The time has come for us to end the sanctions against Iraq, because those sanctions punish the people of Iraq for having Saddam Hussein as their leader. These sanctions have been instrumental in causing the deaths of hundreds of thousands of children.” How do you reconcile those two statements?

I probably should have used a modifier on “Meet the Press.” I should have said smart sanctions. I would oppose some sanctions — no military equipment, nothing for the nuclear industry; most people would agree with that. But I wouldn’t want sanctions on dialysis equipment, on surgical instruments, on oxygen tents, on water-purification chemicals. I wouldn’t want sanctions on nasal gastric tubes or on any kind of medical supplies or anything of use to the water.

Are there any conditions under which you would support military action against anyone?

There are two conditions. After an attack on our country or an imminent threat backed by incontrovertible evidence. Those would be my foundations of principle. But no such evidence exists in case of Iraq, and Iraq has not attacked our country.

You know, the day after attack there was a National Security Council meeting and, according to Bob Woodward in “Bush at War,” in that meeting you had [Defense Secretary Donald] Rumsfeld saying, ‘Let’s go after Iraq.’ That’s on page 49 of his book. Check it out if you haven’t read it already.

So this plan to go after Iraq has been on the boards for a long time.

But would those rules, those “foundations of principle,” have permitted the U.S. to take action to stop the Nazis before Pearl Harbor? It would seem that President Kucinich wouldn’t think we should take any action.

You’re taking about a condition before the advent of the United Nations. Now that we live in a world where there’s a structure and a United Nations charter, Hitler’s activities would have been the subject of a Security Council action and the world community could have responded.

But it sure seems like the United Nations has a fairly high tolerance for genocide. Didn’t the U.N. sit back during the reigns of terror in the Balkans, in Rwanda?

There have been, yes, and I think that an American president can set a standard for engagement throughout the world community. But I don’t think it serves the purpose of this country to conduct its affairs unilaterally. And I don’t think serves the interests of this country to have a unipolar worldview.

You continue to emphasize the United Nations as this beacon of hope and goodness. But there are serious substantive reasons to look askance at the U.N. Libya, Syria and the Sudan — where there is still slavery — have been given seats on the U.N. Human Rights Commission.

Well, then, let’s look at the United States. The United States made an alliance with Saddam Hussein. We sold him biological and chemical weapons agents and then did not object when he gassed his own people. What kind of a president would I be? I’d be the kind of president to reassert America’s moral authority by withdrawing this doctrine of unilateralism and of preemption and of first strike, and by working with the world community on matters of global security wherever those matters rear up. The United States, through working with other nations, can address these issues, but we shouldn’t be expected to be the policeman of the world. And we — if we want to retain any moral authority, we have to look at the consequences of our actions.

So what would President Kucinich do to stop, say, Milosevic’s genocide in the Balkans?

I would go directly to the United Nations and develop a new level of involvement and accountability. We have to get the world community to function as a world community. And the U.S. cannot do that if we’re coming from a position of unilateralism.

You and other opponents of the war keep saying “unilateralism.” But President Bush and Secretary of State Colin Powell have spent a great deal of time lobbying other nations to get their support, and while ultimately we may or may not get the sign-off of the U.N. Security Council or NATO, if military action begins we will be doing it with many other nations. The prime ministers of Denmark, Great Britain, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal and Spain, and the president of the Czech Republic, all published a statement of support for a war against Iraq. We’ll get help from Turkey and Jordan. It’s anticipated that U.S. soldiers will fight alongside those from Australia, Britain, Poland, Spain —

But au contraire! You have to look at how the United States is using its leverage to get this coalition together. You’re proving my point. Let me show you how. If the United States is capable of putting together a coalition to attack Iraq without having proven its case, then look at what the U.S. could do with its leverage. The Institute for Policy Studies put out this study, called “Coalition of the Willing or Coalition of the Coerced?” which has a section called “Levers of U.S. Power.” And it details how the United States uses its military leverage, its political leverage, and uses it across the spectrum to build this coalition.

As the most powerful nation in the world, we’re in position where we can lead the world to peace, as it wants to be led, or to war as we’re doing. The U.S. government has to regain its moral authority by pursuing the interests of all nations, not just one nation.

I could cite to you National Security Directive 45, which is one of those seminal directives that need to be looked at when you’re deciding what we’re doing in the Gulf. And it states: “U.S. interests in the Persian Gulf are vital to the national security. These interests include access to oil and the security and stability of key friendly states in the region.”

That comes from the last Gulf War. And some of those same policy themes are working their way through on this one. Is there anybody in the world who thinks we’re going to war against Iraq for altruistic reasons?

I would imagine that of all the presidents we’ve had, you probably would most emulate Jimmy Carter. Nonetheless, it was during Carter’s administration when Iran seized our hostages and held them for 444 days. For all his idealism, it did nothing to end the fact that there are a lot of people out there who for ideological and other reasons are dead-set on doing us harm.

But the war on Iraq will only make us more vulnerable. The FBI admitted that in Sunday’s New York Times, that if we go to war we’ll be more vulnerable to attack by lone-wolf terrorists. And once we endorse preemption and unilateralism, what’s to stop China from going after Taiwan, or Russia from going back into Chechnya? Or on first strike, what’s to stop either India or Pakistan from doing the same over Kashmir? We have to be careful specifically because the world is so complex.

You know, I started my career in politics in 1967. I’m not new to this. I did not just fall off the Christmas tree. I understand the world is complex. I know that there are people out there who want to hurt other people.

But the only path to the future is for the United States to cooperate internationally with as many nations as it can. If we go at it alone, we will be stuck alone. My philosophy comes from a worldview that looks at the world as one. It’s a holistic view that sees the world as interconnected and interdependent and integrated in so many different ways, which informs my politics. I think this world’s ready, and I think the country’s there.