The bazaar shouts and clatters as a Kurdish shopkeeper tells his story of how he was tortured by the Syrian secret police. “I worked as a border policeman until two years ago when the Mukhabarat took me away. They went through my things and asked me why I had the addresses of so many internationals in my address book. They wanted to know why I was always talking to foreigners. They said the addresses were proof I worked for the CIA and the Mossad.” The Mukhabarat is the police agency responsible for internal security in Syria.

Many Kurds here seem to embrace Americans as friends beyond the natural Kurdish inclination for hospitality. The man invited me to sit down in his shop. We talked about what happened to him over glasses of sweet tea on a polished steel tray.

Khadar, a stout man in his mid-30s, said the police wanted to know about his membership in the KDP, the Kurdistan Democracy Party, and then immediately brought him to Damascus where he was imprisoned for 18 months. “The Mukhabarat said, ‘Don’t worry, you will be here for only one year and then it’s finished,’ and then I am waiting after one year goes by and still nothing. They kept me in a room in Damascus, underground, with no water, no light, and no other people.” When a Bedouin in a red-checkered kaffiyeh head scarf came in to shop, Khadar interrupts his story, saying that he doesn’t like talking about his problems in public, then lowers his voice for the next part.

“The Mukhabarat shocked me with electricity here in these places,” he said, gesturing at his genitals and his feet. “They beat me on my back and legs and I have pain all the time.” Khadar’s eyes were bloodshot and yellow and they spoke of intense stress and ill health.

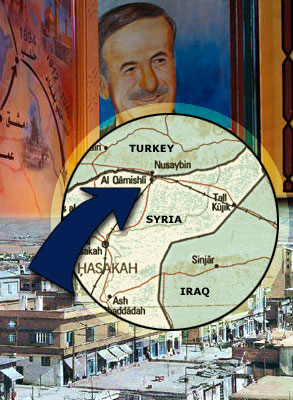

I had been in town only one day and had met Khadar by chance. The encounter helped to confirm widespread reports that the Syrian government makes widespread use of torture. Syria’s human rights violations have not been as extensively documented as Iraq’s, and are thought to be much milder, but the two countries have deep similarities. Syria is poor where Iraq is oil-rich, but they are run by offshoots of the same political party, the Baath Socialists, and both inherited the style of their intelligence agencies from the Soviet Union. It doesn’t come as a bolt from the blue that the secret police here view torture and detention as an exercise in elementary political control. Walking around the streets of Qamishli in northern Syria, the cloying and ever-present malign attention of the cops followed me around town like bad luck. A contagious form. In Russia, this feeling would come in and out like a radio station. Here it’s constant.

Many Kurdish people here date the current round of repression to the months just after Sept. 11, 2001, and President Bush’s declaration that Iraq needed a healthy dose of regime change. If Syrian Kurds are encouraged by sympathy and support from the West, the government feels a corresponding urge to clamp down on anything that resembles independence. It is not hard to see how the two events encourage the Kurdish minority to press for more rights and simultaneously set the government here on edge.

Kurds in Syria are being persecuted for the relative success of the Kurdish-controlled region in Iraq. Although the war hasn’t officially started yet, the tremors are being felt in Qamishli and other towns that have significant Kurdish populations. Qamishli is a transit point for Iraqi Kurdistan. The Iraqi frontier at the Tigris is an hour away by car. Turkey is close enough to yell over the border to friends and be heard. Regional tension escalated on Friday, when Turkey moved troops and equipment to reinforce its border with Iraq, allegedly to ensure that any outbreak of fighting doesn’t send a flood of Kurdish refugees from Northern Iraq into Turkey. But some worried the move could be a first step toward a Turkish invasion of Iraqi Kurdistan. “We oppose a unilateral move into Turkish Iraq,” a State Department official told a Turkish television station.

As I rode the bus from Damascus across the desert to Qamishli I thought a law must be inscribed on a stone somewhere in this mysterious, overexposed emptiness, mandating that Syria’s late President Hafez al-Assad’s portrait, silhouette and crude representation must adorn every structure and moving thing in this country. It will take decades for the son, Bashir, to catch up to the father in the race for state idolatry, but he stands a good chance of getting there if he doesn’t let liberalization get out of hand. There will be token efforts to keep the West from making too many noises, but nothing more. His father left Bashir the secret police to keep an eye on the place, and they are everywhere, too. Hafez al-Assad also left his son the ruin of a Baath party revolution, and the last gasp for secular pan-Arabism. Bin Laden, in his way, has seen to the end of that.

I came to Syria to find a way into Iraqi Kurdistan, and a sense of dread and helplessness is taking hold before the bombs start falling and the oil wells go up in great gouts of flame. Saddam did manage to utter one truth when he said the war was inevitable. We have reached the point where the pocket apocalypse is upon us. It’s time to head for Kurdistan but the way isn’t clear; the neighboring states want us out because they fear for their continued existence.

Most of the countries that border northern Iraq have closed their Kurdish frontiers to Western journalists, and getting into Iraqi Kurdistan gets harder with every passing day. The Syrian-Iraqi frontier is essentially closed, and all requests to cross the border have to go through the secret police in Damascus, where they are ignored. Anyone who wants to go to Iraqi Kurdistan from this country must travel to the extreme northeastern corner of Syria, where the borders of Turkey, Syria and Iraq intersect at the Tigris river. Once there, a dilapidated cable ferry takes people back and forth across the rain-swollen river. Most of the travelers are Kurdish men on the way home to protect their families during the war, and they are happy to be going home. On Thursday, one soaking wet man who had just come off the ferry in the other direction held up a duck he’d caught by the river with his bare hands. When he didn’t think we laughed hard enough, he shoved the panicked duck through the window of our car.

After a few days in Syria, the portraits of Assad the father had started to stand for the Mukhabarat itself and I have trouble seeing the omnipresent mustache and comb-over without thinking about what happens to Syrians who forget their place and say what they think. Most avoid the subject of politics or resort to hilarious on-the-spot celebrations of the regime. One Assyrian Christian told me earnestly a few nights ago, “Syria is wonderful. Everyone is happy, we are all very happy here. The Syrian government is perfect and very good to Christians. We have no problems.” Strangely, I had arrived on the day of national elections for parliament, but the Syrian legislature largely does what the president says, so the odds are that the elections won’t matter except to stir the soup and bring fresh blood into the rubber-stamp body.

On the speeding bus south of Palmyra, patches of white ground in the sun changed places with gray and red. Smooth volcanic escarpments rose out of the horizon that had the shape of human shoulders, the rest of the form invisible, lopped off. Most passengers slept and at Palmyra when the sun was lower, the barren desert went green when the bus rolled over the spring that feeds the oasis. Going over the green land at Palmyra reminded me of walking into the shade of a tree out of the bright sun where the air is cool. As we followed the road north, dust picked up by desert winds knocked the sun into a blank disk for an hour or two and the sky died. North of Deir es Zur, when the sun finally set, there was nothing to look at except a deep black space. We pulled into Qamishli nine hours after leaving Damascus.

The Kurds, an ethnic group estimated at more than 20 million, form roughly a third of the Turkish population and are regarded as a security threat. They are spread throughout an entire region that includes parts of Syria, Turkey, Iraq and Iran. The Turkish government has just put the finishing touches on quelling a Kurdish uprising in its southern provinces using every method at its disposal, including torture and extrajudicial executions. A diplomat would say that Turkey has some improvement ahead of it in the human rights arena. A human rights activist would say more accurately that it has an atrocious record, one of the worst in the world.

Turkey opened up the Turkish-Iraqi border briefly to journalists, then slammed it shut again, and it will probably stay that way for the duration of the war. A photographer friend wrote me in an e-mail. “Here’s the deal: Syria is closed, Turkey is WAY closed, and even Iran now is tricky.” This may be because the Turks have things planned for Kurdistan that they’d prefer the major media not witness. Recently, as a favor to Turkey, the U.S. struck a deal concerning the Kurds in Northern Iraq and it’s difficult not to feel the nasty weight of it in the dry headlines. The U.S. has said that it will allow the Turkish military to occupy a 12-mile swath of Northern Iraq as a “refugee security zone,” meaning that any Kurdish refugees will be kept away from the Turkish border by force. Kurds demonstrated against the U.S.-Turkish arrangement on March 3, in Arbil, and sent a message that the Turkish army would not be welcome.

The new understanding between the U.S. and Turkey means that the Kurds are well on the road to being sold out again, their dreams for an independent state in Northern Iraq buried under a geopolitical calculation made by the United States and Britain. So far, the deal, sweetened by tens of billions of dollars in forgiven debt and economic incentives, has not convinced the Turkish parliament that it should allow U.S. forces to deploy in Turkey. Ali Sayadi, a Kurd living in Fremont, Calif., told me the night before I left for Britain, “What are the Turks afraid of? They are afraid of everything, even the rocks and the mountains.”

In Qamishli, on Monday night, 20 Kurdish exiles collected at the Hotel Mamar, a place with long open halls and chairs arranged for conversation. When I arrive at the hotel led by my friend Joseph, I find the place full of young men and they are arriving from all over the West — the U.K., Canada, the U.S., Germany — and they smoked until the air was opaque. One man mentioned that it’s possible to go to Kurdistan by contacting the Kurdish political groups. All they need for the transit is a passport photo and a copy of my passport, no problem. Beyond this, they are careful about what they say and are reluctant to give their names, but they can’t hide their joy at being able to go home and see their families for the first time in a number of years.

Late at night, their voices, loud and cheerful, reverberate down the halls for hours until the early morning. Their ride arrives at 6:00 a.m. when they are taken to the ferry at Digla on the Tigris River, where they are allowed to pass over into Iraq.

The next morning, at the Kurdistan Democracy Party headquarters in this city, my long-promised help falls through, and I learn that a contact at the KDP office in London has been handing out reams of bad information. The Syrian government has also decided to keep journalists out of Kurdistan in line with Turkey, so Qamishli becomes home for a few days until a new plan is ready, and a route to Kurdistan opens up. Staying much longer doesn’t seem to be an option. The agents of the Mukhabarat told my driver, Mohammed, that it was time for me to leave town. I told him that it wasn’t such a good idea for him to hang around with me, that it would only make them angry, but he won’t listen. Mohammed is a Kurd and now faces retribution for helping a foreign journalist. Tomorrow morning, he’ll knock on the door at 8 and ask me if I’m going to Damascus. I don’t know what I’m going to tell him.