With U.S troops poised on the outskirts of Baghdad, a surreal political phenomenon is unmistakable: So far the loudest establishment voices criticizing the Bush administration’s war plan belong to retired generals, unnamed active military leaders and former Republican officials, while most prominent Democrats either proclaim their support, or remain silent.

Yes, Rep. Dennis Kucinich has called for an end to the bombing, and hundreds of thousands of Americans have demonstrated against the war. But most leading Democrats have muzzled themselves. When Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle noted, accurately, on the eve of the war that the conflict was a result of President Bush having “failed so miserably at diplomacy,” Republicans savaged him. Attack dog Tom DeLay told him to shut up in French (labeling war critics “French” is the slur du jour), and Daschle basically did. The day after the first attacks on Baghdad, House Democratic leader and war critic Nancy Pelosi shocked her San Francisco district by voting in favor of a resolution that expressed “unequivocal support and appreciation” for the way Bush handled the war and its buildup. “The [Democrats’] rhetoric has toned down considerably, which I greatly appreciate,” a smug DeLay told the New York Times this week.

On Wednesday Massachusetts senator and presidential candidate John Kerry broke his self-imposed silence on the war and took up Daschle’s critique, deploring Bush’s “end-run around the U.N.” and calling for “regime change” in the U.S. But when reporters asked him about his remarks, the senator immediately began to backtrack. “It is possible that the word ‘regime change’ is too harsh. Perhaps it is.” Kerry’s backsliding wasn’t as silly as Madonna pulling her antiwar video because, duh, she apparently hadn’t thought about how it might seem once the war actually began, but it was a strange campaign misstep that overmatched Democrats can ill afford.

Why are so many war critics flummoxed by talking about the war? Isn’t it possible to critique the president without giving aid and comfort to the enemy? And is pointing out the effort’s shortcomings the same as glorying in them? I’ve been struggling with these questions since the war began. I’m not an antiwar Democrat; I’m just anti-this war, at this time. I think Saddam is a bigger menace than most of the left seems to; I think his flouting U.N. resolutions merited a tough international response; I thought the world was on its way to crafting one when the Bush administration pulled the plug on diplomacy. Yet even though I opposed its timing, once the war commenced I reflexively wished it would be over quickly.

It’s been a long two weeks. At first it seemed like it might be the cakewalk conservatives promised — Saddam was rumored dead, Iraqis were surrendering, tanks were on the move. Then the coalition bogged down in Umm Qasr, Basra and Nasiriya, and barely touched the north. Now, momentum’s swung back again, with U.S. troops already patrolling Saddam International Airport, but they still could be a long way from victory. And while I didn’t root for the administration’s setbacks in the war’s early going, I have to admit they served to prove its hubris, its dishonesty and the dashing arrogance of the administration’s frightening first-strike doctrine, which the war on Iraq was meant to kick off. Even if the battle for Baghdad ends quickly, there remains plenty to critique.

It’s obvious that in promising a cakewalk Republican neocons ignored the warnings of intelligence agencies and the military, and the soldiers who actually had to fight the war faced more intense resistance than they were prepared for: soldiers who fought desperately rather than deserting Saddam’s forces; guerrilla units, urban combat, even suicide attacks. Lt. Gen. William Wallace got wood-shedded for complaining that “the enemy we’re fighting is a bit different from the one we’d war-gamed against,” but that trivialized the dimensions of the administration’s hubris. Retired generals have blasted Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld for an unrealistic war plan that emphasized technology and air superiority and minimized the role of ground troops backed by heavy artillery. According to the New Yorker’s Seymour Hersh, Rumsfeld nixed six different battle plans that called for more Army divisions. “He wanted to fight this war on the cheap,” one colonel on the ground told the New York Times Monday. “He got what he wanted.” With troops at Baghdad’s borders, commanders in charge of the offensive were still critiquing the shortage of personnel to the Times on Wednesday. “Do we have enough troops? No.”

Yet I won’t be able to enjoy the spectacle of Rumsfeld being proven wrong, if the battle for Baghdad is bloodier than expected, and the war drags on — though the news Thursday made victory seem closer than it did earlier in the week. After all, such miscalculations aren’t just a political blunder; they may cost American and Iraqi lives. (Though I confess to one guilty pleasure: watching his press conference persona shift from Uncle Rummy, the twinkly-eyed, mischievous old salt who used to have the Pentagon press corps eating out of his hand, to the bitchy uncle from Hell, hissing at his once-adoring charges.) Even before Andrew Sullivan — and, to a lesser extent, the Times’ Nicholas Kristof — warned war critics against seeming to glory in the unexpected difficulty of the war, I was feeling torn about whether to feel vindicated by the administration’s apparent misjudgment about the strength of the opposition they would face in Iraq. I never wished for “a million Mogadishus,” and neither did any prominent Democrat or antiwar leader — Sullivan had to search to find something that inflammatory and cruel. But I’m now stunned at the extent to which Republican bullying has worked to paralyze Democratic critics of the war, and I think it’s time to end the silence.

Here’s why the administration’s early miscalculations matter, even if the pace of victory picks up again. First of all, Rumsfeld wanted to fight the war “on the cheap” not because the Pentagon is broke, but because the administration’s outrageous new military doctrine of preemption requires it. What good is declaring you’re for preemptive protective strikes if you can’t go in and prove you mean it? The new Bush doctrine required that the war in Iraq be a cakewalk, so as to send a message to our enemies in Iran, Syria, North Korea — wherever evildoers lurk — that they must tremble before our crushing military might. And if they didn’t get the message, we would have enough troops and firepower left over from Iraq to deliver it more directly. Tragic as the setbacks were for the Americans and Iraqis who lost their lives, from a historical perspective they might serve to prevent more loss of life in rash or unjust U.S. military interventions.

The administration’s arrogance and misjudgments also deserve denunciation if you take seriously the notion that we are trying to liberate the Iraqis from Saddam, and bring democracy to the region. Poor Nicholas Kristof, having scolded doves who glory in the military’s difficulties, found himself in Basra this week, watching a looming humanitarian crisis there. But thanks to his own self-imposed restraints — to refuse to seem to be saying “I told you so” in a time of war — he was unable to call it what it was: the entirely predictable result of our all-but-unilateral strike on Iraq.

Those of us who argued for more time, to bring more of our allies onboard, if not the U.N., did so not because we’re Saddam lovers or Bush haters or we’re secretly French; it was because the difficulty of winning the war, securing the peace and rebuilding Iraq required an international coalition. As one moderate Egyptian told the Times’ Thomas Friedman (who was himself a little too sanguine about the incredible gamble with human life that this invasion represented): “Maybe the Iraqis will eventually stop resisting you. But that will not make this war legitimate. What the U.S. needs to do is make the Iraqis smile. If you do that, people will consider this a success.”

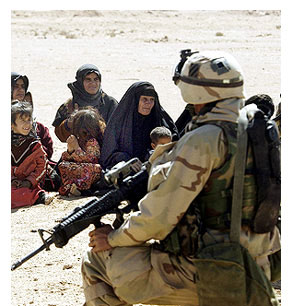

It’s not too late to make the Iraqis smile, of course. But it is too late to take back the pictures, broadcast around an already hostile world, of dead Iraqi children, grieving parents, wounded civilians and the comparatively lucky Iraqis who are merely having to drink sewage-tainted water and scavenge for food, due to delays in humanitarian relief. And let’s be honest: Making Iraqis smile, even belatedly, is a much tougher job than it would have been had this invasion been backed by the U.N., or at least by a more genuine “coalition of the willing,” in which more partners were doing the tough work of bringing humanitarian aid to Iraq even as American forces did the lion’s share of the fighting.

The anti-Saddam alliance built by the White House — which militarily consists almost entirely of the U.S. and Britain, with a small number of Australians and a handful of Poles — would be comical if its impact weren’t so tragic. In 1991, for the first Gulf War, Bush’s father amassed a coalition of 32 nations that sent thousands of troops and committed $70 billion in aid; this time around most leaders of the 40-something countries supposedly backing Bush did little more than affix their names to a “Best of luck with the war!” greeting card. (And as Jake Tapper has reported, some of them are trying to retract even that.) Bush and Rumsfeld are dissembling when they say this coalition is larger than the one assembled in ’91, and they deserve to be called on it every time they say it.

Clearly the administration has sold this war with a combination of deception and distortion. A poll last week found that a majority of Americans think Bush didn’t tell the truth about the cost of the war, either in fiscal terms or in terms of the loss of human life, and I thought once again how silly polling is: The fact that Bush didn’t tell the truth about this war and its costs is not a matter of opinion, it’s fact, and he should pay for it.

But as U.S. forces close in on Baghdad, what should war critics do and say? The antiwar left loses me with talk of a quagmire in Iraq. Some of it sounds like wishful thinking, and it will likely be proven wrong: This war will probably be won in months, not years, and it could still end in only weeks — though the battle for Baghdad is so fraught with potential nightmares it makes realistic predictions impossible. (Coalition forces still do not decisively control any Iraqi city.) Yet all week the lefty news site Common Dreams has been awash in stories about the coming U.S. defeat, with headlines like “It Will End in Disaster” and “The Monster of Baghdad is Now the Hero of Arabia” and “The Bright Side of War.” I recognize that reporting bad news isn’t the same as enjoying it, but some on the left seem to be wallowing in it, a little too self-satisfied that the war has seemed to be going badly.

The other problem with all the talk of a “quagmire” is that it seems to lead to comparisons with Vietnam, from which it’s just a short but dishonest intellectual hop to thinking of defiant Iraqis as the Viet Cong. But it’s obvious that the “resistance” to American and British forces can’t be considered any kind of mass popular uprising; so far it’s mostly the result of Saddam’s brutal coercion. The reports of fedayeen shooting soldiers who try to desert and civilians attempting to flee from combat are chilling. Read Phillip Robertson’s haunting report from northern Iraq on Saddam’s “execution committees” that keep soldiers from deserting. On Wednesday, Iraqis were once again cheering invading troops as liberators in the city of Najaf. There will no doubt be more scenes like that to come.

Opponents of this war can’t be invested in the quagmire theory, or in the myth of widespread popular Iraqi resistance to the U.S, or a pan-Arab uprising against the coalition. For starters, it’s morally corrupt to root for a dictator like Saddam under any circumstances. And those banking on a “big muddy” scenario in Iraq risk further political marginalization if the pace of victory accelerates again. If the war was wrong — and I believe its timing and unilateralism certainly were — it will remain wrong even if Saddam’s regime is toppled sooner than the quagmire theorists expect.

So what do opponents of the war, and the president’s policy in prosecuting it, do now? I can’t support Kucinich’s call to stop the fighting immediately; it would only let Saddam’s regime come in and crush those who’ve risen up against him, and submit the country to further terror and chaos. On the other hand, I think Rumsfeld’s sneering insistence that a cease-fire is completely off the table is frightening: Should the battle of Baghdad bog down, should there be a reasonable chance to resume diplomatic efforts to remove Saddam Hussein, why wouldn’t we stop the killing and talk about it? Democrats should be ready to call for that if there’s evidence there’s still a diplomatic solution to this tragedy.

Even with the war yet to be won, the Bush administration is trying to impose Rumsfeld’s military model on postwar Iraq, handing power to the Defense Department while marginalizing Colin Powell’s State Department, not to mention the United Nations. The indefatigable Powell is of course fighting back, but Democrats need to speak out against the Pentagon power grab. Meanwhile, another military leader marginalized by Rumsfeld, Army chief of staff Eric Shinseki, told Congress it would take hundreds of thousands of troops to occupy Iraq after the war, and was slapped by deputy Paul Wolfowitz as “wildly off the mark.” The cakewalk conservatives’ arrogance about the war will be extended to the peace, whenever it comes, and they deserve to be fought at every opportunity.

Some Democrats still insist silence is politically wise. “Democrats don’t need to do any criticism of the Bush administration right now,” consultant Jenny Backus told the Times. “The unnamed generals are doing that job for us.” But top Democrats have been preaching silence as strategy since before the midterm elections, and the party’s shellacking at the polls cost them all credibility. Americans won’t let them sit this fight out. Yes, Democrats must choose their words carefully, they should critique the president fairly and cogently, they should always think about the impact of their words on the troops. But the GOP attack dogs will come after them whatever they do.

In a dishonest piece of writing in the Weekly Standard this week, “The War for Liberalism,” cakewalk conservative William Kristol described the Democrats as divided between brave “Dick Gephardt liberals,” the “patriots” who back the war-supporting former minority leader, and the despicable “Dominique de Villepin left,” — there’s the French slur again, after the foreign minister who led the U.N. opposition to Bush’s war — whose adherents “hate conservatives with a passion that seems to burn brighter than their love of America, and so, like M. de Villepin, they can barely bring themselves to call for an American victory.” And though Kristol’s list of de Villipin leftists is short on names, one of the handful he includes is Nancy Pelosi — despite her vote “in support and appreciation” of Bush’s conduct of the war.

Kristol is wrong: Most war critics still hope for an American victory, one that results in as little loss of life and as much freedom for Iraqis as possible. But it’s already clear that he and his neocon friends designed a war that wouldn’t ensure we could do either, and they and their war deserve criticism. There will be a reckoning for bullies like Kristol, and all the pampered, pink-cheeked scions of no-sacrifice who sold this war dishonestly. Yet I fear there will be a lot more Iraqis and Americans dead before that day comes.