There was a crowd around the pit, and the old men gestured to the children to go down in and dig with scraps of wood. After moving back some of the red earth, a young Arab boy held up a human bone, a femur. The rest of the body was missing. More boys left the edge of the pit and dug with their hands at the direction of the older men. A few minutes later, an 8-year-old held up small bones of the kind that sit at the top of a human spine, two delicate vertebrae. Other things had come to the surface. The sole of a boot, a scrap of military uniform, a tangle of black electrical wire. The recently opened pit gave off a faint musty smell. One of the boys brought the sole of the boot over so I could see it and write down the markings.

The scattered bones in the hole were the remains of a single person. Looking into the pit, I thought there should be more bones. Someone asked, “Where are the head and the hands?” and he said it because the excavators failed to find a skull and the small bones of fingers. When the boys found a new bone, or any new piece of evidence, they were excited and climbed around the pit in the morning sun, showing their find to the crowd. There were many more bodies still covered by earth, because the peshmerga bulldozer had exposed only a cross section of a trench about 10 feet long. “I think that they are soldiers because they have canteens and boots. Some of their hands were bound,” a commander named Khalid explained at the Mosul checkpoint. He didn’t know any more about who was buried there or how they had died. It was Wednesday, and we had stopped just outside of Mosul, at a place called Karama. It was in the shadow of the Iraqi state TV tower.

The pit was the open part of a mass grave, the dead laid end to end in rows 60 feet long, and the excavation was being done roughly. The bulldozer had churned up the remains where it cut across the trench. We counted 32 trenches by walking across the field looking for the raised humps of earth that did not have grass growing on them. They were easy to find since they had been dug at regular intervals in the field, in careful rows. It was enough real estate for hundreds of corpses. There was a new civilian graveyard nearby. One man said that there were new graves on top of the old mass graves and that the government had sold the land to neighboring families.

Imad Mohammed, a taxi driver who lives near the site, told me that he saw a burial in 1991. “I saw a bulldozer come and men took out a body wearing military clothes. The men who took the body out were Baath Party members who came in a military vehicle and it was full of bodies. I wanted to be near the place but it was not possible.” I asked him what he thought happened and Mohammed said, “I think the men were killed in the war, but they didn’t send the bodies to the families. They were put in a special place not to make problems.” Everyone agreed on the year of the burials but nothing else.

There were hundreds of people at the site, and they were telling their own stories about how the bodies came to be there. One man talked about how refrigerator trucks full of bodies came in the middle of the night and how the residents found the grave site by the smell. This man then told the same story to a visiting American official who seemed to believe it. The crowd were also asking questions, trying to put together the pieces in their own way; when they didn’t have enough information they made up the rest. The American official wanted to know the name of the Iraqi responsible for the area during the regime, but the crowd couldn’t help him.

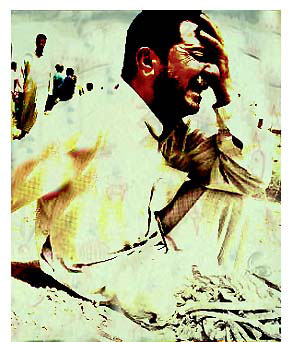

Iraq is a country populated by missing people — their absence creates a pressure that is palpable everywhere. During the years of the dictatorship people went into a startling array of situations and didn’t come out. A rough tally of the nearly three decades of Saddam’s rule puts the number of destroyed people well over a million. The Iran-Iraq war, the first Gulf War, the secret police in the middle of the night, the secret police in the middle of the day. There were the uprisings in 1991 that the regime suppressed, arresting and destroying those involved. There is the most recent war, a bloody bookend for the regime. Thousands of conscripts died as they were forced by military intelligence units — under the threat of death — to defend Iraq from the U.S. invasion.

At the close of the ’80s, there was al Anfal, a genocidal sweep through the north that the Kurds say consumed 180,000 people, and Ali Hassan Masjid, Saddam’s cousin, said: “No, it wasn’t 200,000, it was 100,000.” He is more notoriously known as “Chemical Ali,” and he just wanted to set the record straight because he had done the killing. It is unlikely that there will ever be a proper census of the missing.

Here is an example of what Iraqis believe: In Baghdad, a crowd heard a rumor that there were voices in the walls of an overpass and they ran to rescue the people imprisoned inside the concrete. Anyone who sees the tape feels like there is something wrong with their chest. I heard a colleague watching the footage draw in her breath with a sharp sound. Of course, the would-be rescuers found only a dusty service shaft and no sign of prisoners. Someone said they heard voices in the walls and that’s how it started. The crowd lifted a cameraman on their shoulders because they wanted him to record the joyous moment, but he only recorded emptiness and more questions.

People in Baghdad and the rest of Iraq believe that there are thousands of people trapped in secret underground prisons all over the country, and they believe it because they have become mad with grief and hope. It is natural because they have not heard about the fate of members of their families. The missing are not in underground prisons, they are in scattered grave sites, and new ones are being discovered every day. Things keep coming to the surface.

After we left the grave site we drove to Mosul to see the pretender to the governorship, an Arab named Misaan al Jibouri, who once held a high position in the Baath Party as a business partner of Uday Hussein. Seizing what he thought was a political opportunity, he gave a speech outside the governorate building in downtown Mosul last Tuesday, a day that was marked by bloodshed and rioting. After al Jibouri’s speech, the crowd burned his car and left the black hulk upside down on the sidewalk. A hospital worker said a few days after the riot, “Look, al Jibouri is only here 10 minutes and he kills 10 people.” In fact it was the American soldiers who fired on the crowd, but the order of events is confused. In one version supported by two independent eyewitnesses, the Americans had been fired on first by the Iraqis and fired warning shots in the air before shooting to kill. Mosul residents alternately blame al Jibouri and the Americans for the deaths.

Misaan al Jibouri has taken for himself the summer palace of the most unloved man in Iraq, Ali Hassan Masjid, Saddam’s cousin. It took us an hour to find the place because it was nestled in a stand of eucalyptus trees, the main house set away from the road. When we stopped for directions at the Kurdistan Democracy Party branch office, an Arab man was coming forward to report another mass grave at a place called Haddar and said that he was afraid to go up there by himself but would go to where graves were if peshmerga guards went with him. The fresh reports of graves at Haddar and another place called Badosh, and the fact that a Baathist friend of Uday Hussein was living in Chemical Ali’s palace and trying to make himself boss of Mosul, gave a sickly resonance to the day.

The palace sits on the banks of the Tigris River, surrounded by beds of roses. It smelled sweet. As we pulled up, a convoy of Kurdish officials from Dohuk was just arriving for a meeting with al Jibouri, a detail I had not expected. It turns out that al Jibouri has no official title but maintains close links with senior Kurdish officials. He also has a good relationship with the Kurdish government and has enjoyed the protection of Massoud Barzani, the leader of the KDP. The new resident of the palace was clearly busy trying to consolidate some political power with the Kurds of Dohuk, but it wasn’t clear if it was working.

I stopped by the palace because I wanted to see what he would say about the shootings at the governorate building and his ambitions to join the government. At the gates of the palace, an al Jibouri relative named Nabil ushered me into a waiting room with the Kurdish officials. They looked embarrassed.

Al Jibouri didn’t introduce himself. He didn’t answer many questions, but over tea he began a high-speed monologue about the merits of democracy and how the Arabs do not like to be ordered around by Americans. “An Arab man thinks that the American army is coming from Jews and Christians. He thinks, ‘We don’t like these strange people.'” Al Jibouri asked where I was from and when I told him he said that he knew that San Francisco was a stronghold of the Jewish lobby. I told him that I had no idea what he meant by that, but he rattled on, telling me not to deny it and went on to say, apropos of nothing, that even Saddam understood something about democracy. Arabs should not be dictated to, but it seemed that he was talking about himself. Al Jibouri was trying to tell me that Americans had to respect the Arab culture and traditions and watch their step in Mosul or things would go horribly wrong. Al Jibouri made a conciliatory remark after refusing to talk about the shooting incident and his burned car.

I asked al Jibouri why he’d left Iraq in 1989. He said: “I was part of a plot to kill Saddam on Jan. 6, 1990, on Army National Day. Saddam rounded up members of my family and killed them in 1990 and 1992. Saddam killed my brother and cousin in 1993.” And he said it in such an excited way, as if to demonstrate that he was a true member of the Iraqi opposition. Al Jibouri glossed over the fact that at the time of the supposed coup attempt, he had already fled for Jordan.

Who is al Jibouri? He spent his career as a Baath Party functionary and was accepted by the Mukhabarat, the Iraqi secret police, in the ’70s after a stint in the army. Following his training, he was given a job with the Baath Party newspaper. Now for a rapid rise and an equally rapid decline in his political fortunes. During the late ’70s and early ’80s, he cultivated his connections with Saddam and the ruling family, finally going into business with Uday Hussein. A man who knew about the deals said that al Jibouri worked in a factory for military uniforms but that in 1989 the relationship went sour and al Jibouri left Iraq, first for Jordan, then for Syria and Turkey. Senior Kurdish officials later welcomed al Jibouri into Kurdistan for reasons no one I spoke to could adequately explain.

From 1999 to October 2002, al Jibouri enjoyed a lucrative partnership in the Mir Co., a major importer of medicine for northern Iraq that also has strong Kurdistan Democracy Party connections. The arrangement collapsed after he was accused of embezzling large sums of money by submitting fake invoices from Dutch suppliers. Al Jibouri is seen as untrustworthy, a species of dangerous fool, by people who have worked with him. In person, he is alternately magnanimous and paranoid, whispering and bellowing in an unpredictable order.

After his monologue over tea, al Jibouri and I walked through a garden to his guesthouse on the Tigris. The river went by in a silver sheet. In a meeting room that faced the water, members of his tribe had gathered to wish him well and offer their assistance; they stood around the room with their hands clasped in front of them. No one spoke while they waited for al Jibouri to address them. The respected elders of the al Jibouri tribe wore their formal black cloaks with gold trim and white headdresses. When it was time, I shook their hands and the men were gracious and kind in their manner. They seemed to have little in common with the new owner of the palace, and I had trouble believing al Jibouri’s story about the Arab mind, because the older men did not seem to harbor hatred and suspicion of foreigners.

The elders were traditional men coming to pay their respects because it was required of them. Al Jibouri then welcomed them and asked each man if he needed anything, and they each declined. He offered his new home to them, and a few accepted his invitation.

We walked through the pungent smell of the roses toward Ali Hassan Masjid’s helicopter pad. Al Jibouri stopped in the center of the circle and gestured around him in a wide arc, and said: “You are welcome here anytime.”

There is an image that remains from that afternoon: At a traditional Arab lunch he served his guests, al Jibouri had brought out a dish in which the bodies of entire sheep were served on enormous beds of rice. On a nearby plate there was an exposed spine that lay with the bundle of nerves still running down it in a white cord. I could not eat it.

[For a directory of Phillip Robertson’s past stories from Iraq, click here.]