It seems churlish to pick apart a movie as competently made as “Owning Mahowny,” which tells the story of Dan Mahowny, an unassuming-looking Toronto banker — played here by Philip Seymour Hoffman — who feeds his gambling habit by embezzling millions of dollars from his workplace. Director Richard Kwietniowski (“Love and Death on Long Island”) lets the story unfold so casually, and so naturally, that even as Mahowny digs himself deeper and deeper into this extremely illegal hole, you’re almost lulled into believing he’s doing exactly the right thing.

And Hoffman is just the actor to pull off this type of character — his face has that instant-best-friend quality. Even when he’s playing a man who’s wreaking damage right and left, he’s trustworthy beyond the scope of our imagination. It would be the ultimate betrayal of our faith in our own judgment not to believe in that earnest, good-natured face.

And yet “Owning Mahowny” just doesn’t give us enough to hold onto, perhaps partly because it’s executed with so much restraint and subtlety. It’s often a tense, uncomfortable little movie, particularly in the way it invites us to watch as a man ruins himself. We always feel sympathy for Mahowny, as well as some exhilaration that he gets away with his schemes for as long as he does (he keeps going back for more stacks of cash, fiddling with his clients’ paperwork to get it). It’s also based on a true story: In the early ’80s, the real Dan Mahowny stole, bit by bit, some $10.2 million in bank funds simply to sustain the thrill he got from gambling. (The movie was adapted by Kwietniowski from Gary Ross’ book “Stung.”)

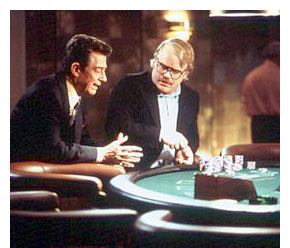

Mahowny’s pudgy ordinariness is key to the story — so key that his unremarkability almost turns the movie into a nonstory. Hoffman is a wonderful actor. Although this role doesn’t provide any outlet for his sensuality, I think he’s one of the sexiest actors working today — his sex appeal rests almost as much in his solid, comfortable build as it does in his timing, his expressiveness and his soul. I’ve never seen Hoffman give a bad performance, including this one. But he plays Mahowny as a completely recessive character — we like him instantly, even though we’re never quite sure what he’s thinking. Chamelion-like, Mahowny fits so anonymously into all types of surroundings that he virtually disappears into them: You’d expect him to look wholly natural wearing a boxy, ill-fitting suit as he hunches over his not-very-lavish banker’s desk; what’s weird is that he also looks perfectly at home scrunched over the gaming tables in the cheapie-glam Atlantic City, N.J., casino he most often frequents (run by a deliciously oily John Hurt). He’s at home everywhere, including his own skin. Mahowny knows he loves to gamble, and knows he loves it solely for the rush it gives him. He’s so honest about his compulsion that he almost makes you forget it’s an illness.

This is a case of an actor making the perfect choice for a character and following through to the letter, only to end up with exactly the effect he wanted: A character who squirms right out of our grasp, never lingering in our imagination as he should. He’s the movie’s anchor, but he’s such a vaporous one, he leaves us feeling adrift. The characters around him feel similarly unrooted: Hurt, who instantly latches onto Mahowny as a high roller and makes absurdly funny attempts to keep him happy as a “client,” wears out his own joke after a while. And Minnie Driver, as Mahowny’s long-suffering girlfriend Belinda, trundles faithfully through the picture in a highly unbelievable Dynel pageboy hairdo and oversize goggle glasses.

Somehow, as bad a boyfriend risk as Mahowny is, you can’t help thinking that he could do better than this dowdy acorn of a girl. She stands by her man, virtuously, and after he’s worked through his serious troubles, she’s the jackpot at the end of his rainbow. She’s supposed to represent the quietly redemptive power of love. The sad part is that she makes those little cherries and lemons and limes that pop up in the slot machines look pretty exciting.