Opponents of President Bush are hoping that he suffers the same political fate his father did in 1992 by winning a war with Iraq only to lose reelection at home because of a soft economy. But with the shooting in the latest Iraq war mostly over and the 2004 campaign well underway, influential Democratic insiders are warning that may be wishful thinking. Young Bush, they say, has two things his father did not: the ongoing war on terrorism and bare-knuckled political advisor Karl Rove.

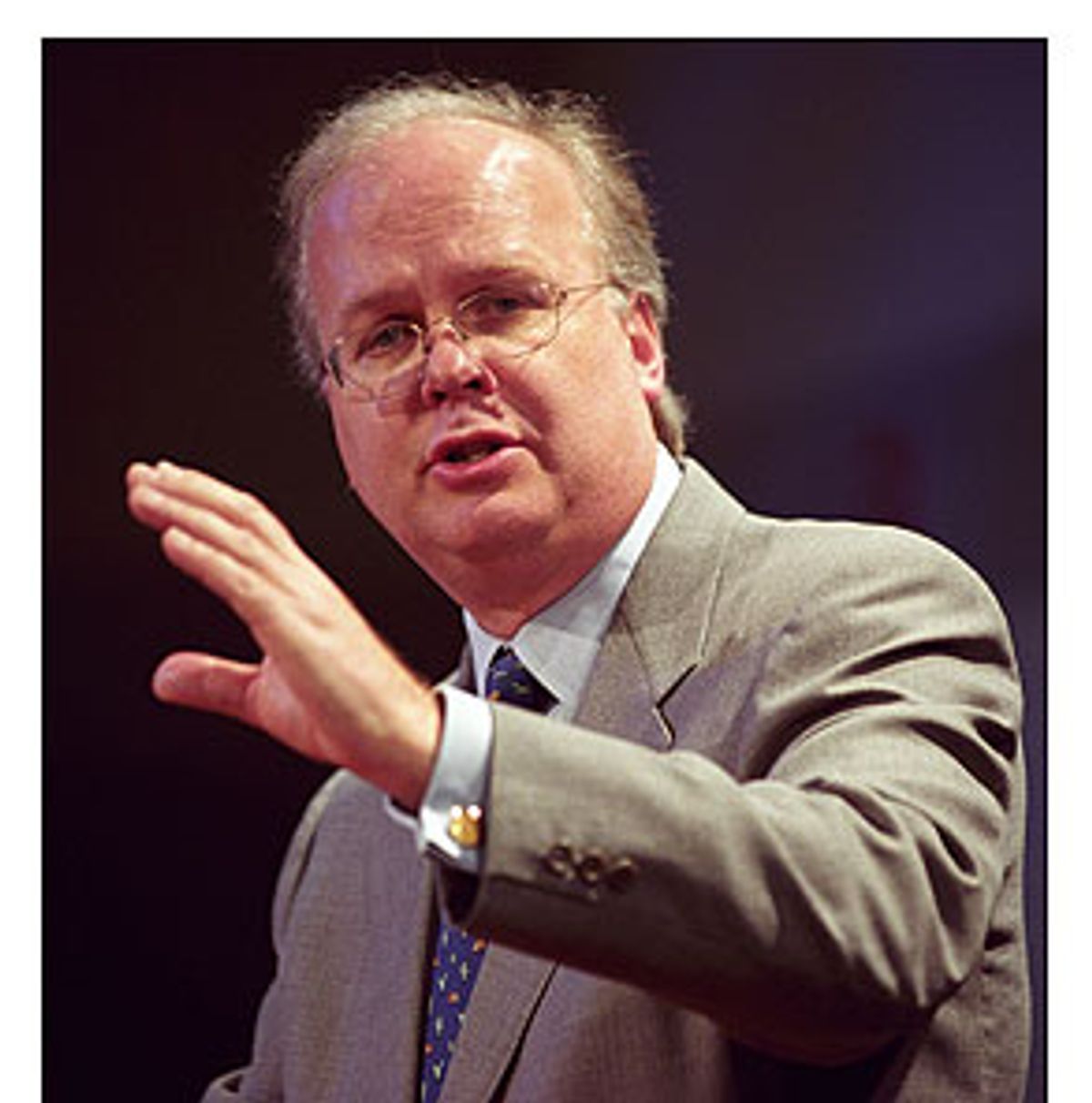

Rove plays politics with national security -- and public insecurity -- in ways that Bush Sr.'s White House never dreamed of. Since the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, the administration has boldly, and at times brazenly, exploited the aftermath for political gain. Before the Republicans' triumphant 2002 midterm election victories, the White House used terror-related issues and the specter of war with Iraq to keep timid Democrats off balance and the staggering economy off of Page 1. And it appears certain that Rove will employ a similar script in the 18 months before the next election.

"The Democratic Party keeps putting out talking points that are all about 1992 [comparisons], but I say '92 is not a playbook we can pull out," says Donna Brazile, who managed Al Gore's 2000 presidential campaign. "Except for the Bush DNA and the same last name, that's where the similarities end. George Bush is beatable -- he's a lousy educator and a lousy economist -- but he's added a very important element to his résumé since 9/11, commander in chief. Democrats must have a very good answer to how they will protect American citizens. It's national security, stupid."

"This is not going to be a repeat of 1992, this White House is too smart for that," agrees James Zogby, a senior advisor to the Gore campaign and now president of the Arab American Institute. "They're not going to let the war culture fade. Bush is a 48 percent president acting like an 80 percent one and the difference is 9/11. He knows that and he's not going to let go of it. The war on terrorism can be a never-ending war, but without the fatigue."

That perpetual-war approach contrasts sharply with Gulf War I, which came to an abrupt end and was not tied to any larger crusade. That allowed Bush Sr. to claim victory in the short term, but allowed Americans to turn their attention back to domestic issues, such as the weak economy and a president who was seen as weak on economic issues.

Today, in Rove's the hands, the permanent war on terrorism is like a political gold mine. "Everything, including a war, is a potential campaign event for Karl," says James Moore, coauthor with Wayne Slater of "Bush's Brain: How Karl Rove Made George W. Bush Presidential." "He has great a skill at keeping messages simple and accessible. And the message today is the war and economy are wrapped up in security, that there's unfinished business with the war on terrorism and why would you change commander in chief in the middle of war? It's a helluva salable message."

With little-known presidential Democratic candidates currently trailing Bush badly in the polls, particularly over the issue of national security, Rove and the increasingly brash White House are openly using the might of the U.S. military to make sure this president does not suffer the same fate as his father, who chronically battled his own wimp factor.

"Rove's doing things a bit more boldly than he's done in the past because he's able to get away with them," says Moore, citing Bush's high-profile visit to an aircraft carrier last week. "The president was essentially a draft-dodger during the Vietnam War -- he disappeared for his last year of his [National Guard] flight service -- yet he's portrayed in a flight suit as some kind of war hero. But Democrats and the national media never address the hypocrisy," says Moore. "Both Karl Rove and the White House say, 'Why stop?' It won't come back to haunt them because the environment changed after 9/11."

The contrast in how Bush handles military celebrations before and after 9/11 is telling. Back in April 2001, Bush opted to stay out of the spotlight during the emotional homecoming for 24 crew members of a U.S. surveillance plane who were forced to land on China's Hainan Island after a mid-air collision that left one Chinese pilot dead. Following 11 tense days of negotiation, the administration won the crew's freedom.

When the appreciative servicemen and women touched down at Whidbey Island Naval Air Station 50 miles north of Seattle, they climbed onto a podium and shook hands with local dignitaries and politicians, while throngs welcomed them home. Bush, however, was not among them. Bush insisted he did not want to insert himself into the private moment of a family reunion, and that he wanted to avoid the "hoopla."

Fast-forward 25 months and it appears Bush's aversion to hoopla -- especially military hoopla -- has been cured, undoubtedly with the help of Rove. Last week, he staged perhaps the most elaborate photo-op in history aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln aircraft carrier, which was homeward bound from the Persian Gulf. Of course, Bush didn't just arrive on the ship; he donned a full flight suit and flew in an S-3B Viking jet that was snared by the Lincoln's flight deck restraining wire. The event generated extraordinarily rich, symbolic images for the White House.

Only after the carefully staged television event was over did it become clear the that the White House misled reporters when it insisted Bush had to fly in a jet to the Lincoln, rather than in a traditional and less dramatic helicopter, because the ship was hundreds of miles offshore; in fact, the Lincoln was less than 40 miles from San Diego when Bush touched down. The Navy slowed the ship's approach to port in order to give Bush enough time to arrive on the decks before the Lincoln docked. Then the crew maneuvered the gigantic ship in order to give the White House the Pacific Ocean as a backdrop, not the quickly approaching San Diego coastline.

Critics suggest it was simply the latest in a long list of crass attempts by the White House to play politics with national security issues related to either 9/11 or the war with Iraq. For instance, the administration announced the creation of the Department of Homeland Security on June 6, 2002, in order to drown out the news of FBI agent Colleen Rowley's testimony before Congress that same day. She detailed the memo she wrote to superiors that might have helped prevent the 9/11 attacks, had the FBI under Bush's watch not ignored the memo.

Actually, the maneuvers go back to Sept. 11 itself, when the White House and Rove were spinning furiously to counter criticism that Bush spent the day hop-scotching around the country on Air Force One, from Florida to Louisiana and Nebraska before finally returning to the White House where he made some ineffectual remarks to a terrified nation. Two days after the attacks, and still scrambling to fix the problem, Rove and the administration announced it had uncovered "credible evidence" the White House and Air Force One had been terrorist targets on Sept. 11, which explained why Bush made so many unscheduled stops and took so long to return to the White House.

The tactic stopped the political bleeding for Bush, with critics suddenly reluctant to question his questionable Sept. 11 response. By the end of the month though, the story fell apart and the White House all but conceded it had no "credible evidence" that any such threats were ever made against Air Force One. "Karl plays outside the bounds -- whatever is necessary to win," says Moore.

Last year, the White House gave a photo taken of Bush aboard Air Force One on Sept. 11 to the Republican Party, which sold the photo to political donors. Democrats denounced the move as blatant attempt to cash in on the national tragedy. The charge apparently had no effect. More recently, in another audacious move, the Republican Party broke a longstanding agreement with Democrats and moved its nominating convention from August to September. That means come 2004, Bush will receive his party's nomination in New York City just days before he attends memorials marking the third anniversary of the World Trade Center attacks. The Republicans' convention announcement caused barely a ripple of protest among pundits or members of the passive opposition party.

"The White House doesn't even care that the Democratic Party exists," says one Democratic operative, who sees the current dynamic as just the latest example of how the two parties approach politics by different sets of rules. "Democrats play the game the way children play marbles on the playground," the operative said. "Republicans play it like they own the marbles and the playground ... We worry about what the editorial pages will say and try not to hurt anybody's feeling. They play it the way the game's supposed to be played."

The game has certainly changed since Bush's father was in the White House and looked to James Baker, the former secretary of state, for political guidance following Gulf War I. "There's no question Bush Sr. was far less of a political president than this president," say Rick Shenkman, editor of George Mason University's History News Network. Aside from a victory parade in Washington and a Desert Storm video shown at the '92 Republican Convention, "he didn't really seek to exploit the Gulf War victory," Shenkman says. "He could've done a lot more rah-rah stuff."

Moore and others trace the difference directly to the differences between Baker and Rove. "Baker fancied himself a diplomat and didn't like retail politics, and when he did them it was almost pro forma," says Moore. By contrast, "Rove is absolutely a political animal and lives for that stuff.

"W. implicitly trusts Rove in a way his father did not trust James Baker," Moore adds. "W. is able to be freed up, to do what he does because he knows Karl has everything under control. W. doesn't fret about a backlash over the absurdity of flying out to Lincoln, because Karl has it all perfectly planned. The timing is right, the image is right, the message is right. And the press won't ask questions."

That's another crucial factor working in favor of the White House that Bush Sr. did not have in 1992 -- a tame press corps that, like many Democrats, feels uncomfortable asking pointed questions of a wartime president. That's when the press isn't simply fawning over Bush. In NBC's April special, "Commander in Chief: Inside the White House at War," anchor Tom Brokaw spent the first 10 minutes of his exclusive interview walking Bush through the decision to launch an opportunity strike against Saddam Hussein before the scheduled start of the attack after getting intelligence that Hussein was inside a Baghdad bunker. The strike was portrayed as a victory of American intelligence and military ingenuity; Brokaw never told viewers that most intelligence analysts believe Saddam survived the missile attack.

Despite the advantages that come with Rove's expert manipulation of the wartime political climate, it's still possible the president's reelection bid could collapse between now and 2004. If the economy continues to stagnate and public opinion remains opposed to his tax cut proposal, the emerging narrative of his reelection could be that Bush is doomed to repeat his father's defeat.

"If you assume the war in Iraq is over and reconstruction is messy and if there aren't new instances of terrorism, I don't think he's in a lot better shape than his father was in terms of the context for reelection," says Jeremy Rosner, a Democratic pollster and national security specialist. "This campaign is not over by any means. Bush could still win the war and lose the election."

And the fact is his postwar jump in the polls has not been all that impressive, and nowhere near as dramatic as his father's following Gulf War I. According to surveys conducted by Newsweek, Bush's job approval ratings today are up just 13 points from the eve of the war.

Still, some Democrats, surveying the candidates and the media landscape those candidates must traverse, worry about the coming election. "I'm optimistic because I'm a fighter, but we've got a long way to go," says Brazile. "This could be 1972 for Democrats," she says, referring to Republican Richard Nixon's rout of Democratic Sen. George McGovern.

"There's nobody to challenge the president," adds Democrat Zogby. "The debate is theirs, it's on their turf, and Democrats and the press are too afraid to ask questions. I fear for what's going to happen to Democrats in 2004."

Shares