Darrell Issa is a second-term Republican congressman from Southern California. He’s as conservative as they come — pro-business and anti-abortion, supports prayer in school, opposes affirmative action, never met a tax cut or an oil well he didn’t like. In socially liberal California, he’s got exactly no chance of ever winning statewide office.

And yet, he just might be the state’s next governor.

California Gov. Gray Davis was reelected just seven months ago. Although you’d be hard-pressed to find a single Californian who actually likes Davis, he was able to win reelection because the Republicans fielded a neophyte challenger — bumbling businessman Bill Simon — who was as clueless as Davis was conniving. Davis beat Simon by 47 percent to 42 percent in the most expensive gubernatorial race in California history.

But for Republicans in George W. Bush’s America, defeat is not an option. If the vote in Florida goes against you, make them stop counting the ballots. If the Senate Democrats won’t confirm your most extreme judicial nominees, change the rules so they can’t filibuster anymore. If Texas Democrats won’t show up to vote on your crudely partisan redistricting plan, tell the federal Homeland Security forces to hunt ’em down and bring ’em in.

And if you can’t win a regular election against the Democratic governor of California, just wait a few months and then demand the right to try again.

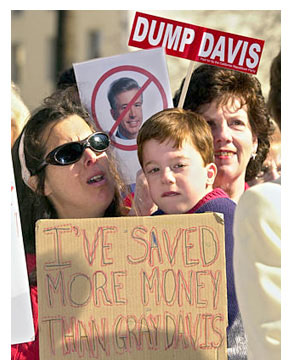

Seizing on a provision in the California Constitution that allows voters to recall the governor for no reason at all, Republicans launched a recall drive earlier this year. Although Davis is suffering incredible difficulty in navigating California’s dire fiscal straits — the state faces a huge budget deficit brought on by the foundering national economy, the dot-com bust and the state’s failed effort at energy deregulation — the political establishment wrote off the recall proponents as ideological windmill-tilters. But then came Darrell Issa and his money. Issa announced that he would run for governor in a recall election — and that he was putting up $700,000 to ensure that the recall drive made it to the ballot.

Overnight, the recall has become a real possibility, and Democrats are apoplectic — not because they might lose Gray Davis, a man they loathe nearly as much as the Republicans do, but because someone like Darrell Issa might be able to take his place.

“We won an election fair and square,” complains Kristen Spalding, chief of staff for the California Labor Federation, a coalition of unions that backed Davis in 2002. “Six months later, the Republicans want a ‘do-over.’ It’s not the way this works. There has been no malfeasance, no legitimate reason for a recall. It’s just sour grapes.”

But for some, it’s something much worse. It’s another example of Republicans’ manipulating the rules and procedures of the democratic process to ensure their own partisan gain, no matter the cost in taxpayer money or public cynicism. It happened in 1995 when House Speaker Newt Gingrich led congressional Republicans in a shutdown of the federal government. It happened in the right’s relentless pursuit of the Whitewater witch hunt against Bill and Hillary Clinton, and again in the impeachment of President Clinton.

If the recall drive makes the California ballot, voters will be asked not just to decide Davis’ fate but also to name his replacement if Davis is recalled. There is no primary and no runoff; it would be remarkably easy for a candidate of any party to get on the ballot, and no matter how many candidates there are, whoever wins a plurality of the vote wins the governor’s office. That confluence of circumstances favors a hard-right candidate like Issa, whose base of loyalists will turn out to dump Davis and then vote solidly for one of their own to replace him. For Issa, it’s a custom-made election, paid for in small part by his contributions to the recall drive and in much larger part — some say $30 million worth — by the California taxpayers.

“This is a blatant abuse of the recall process,” says Craig Holman, who follows campaign finance issues for Public Citizen’s Congress Watch and drafted a campaign finance reform law adopted by California voters in 1988. “The recall process is intended as a once-in-a-millennium procedure that would be invoked to remove some office holder for, most likely, criminal activity. This is clearly not that. It’s Darrell Issa using his money to try to set up a procedure in which he could potentially get elected governor realizing that he can’t do it if he followed the normal route.”

Recall supporters reject the notion that recall is part of some larger Republican power grab. For them, this is a campaign about a disliked and dishonest Democrat, a politician whose sole policy goal often seems to be the collection of campaign contributions, a governor who lied about the depths of the state’s budget crisis in order to win reelection.

“This is about Gray Davis — it’s unique to California and unique to him,” said David Gilliard, director of Rescue California, the organization running the recall drive.

And for the governor, that’s a problem. Gray Davis has spent his political life making sure elections involving Gray Davis aren’t about Gray Davis. He won his first gubernatorial election in 1998 by painting his Republican opponent, Attorney General Dan Lungren, as a right-wing zealot. He won reelection in 2002 by running what amounted to two separate negative campaigns. First, he invested millions of dollars in the Republican primary to make sure that his strongest potential challenger, former Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan, was defeated by a lesser Republican and didn’t make it to the general election. Then he waged a nasty and expensive war against Simon, portraying him — not entirely unfairly — as a stumbling businessman with hard-right political views. Throughout the campaigns, Davis gave voters much to dislike about his opponents, but little to like about himself.

“Gray Davis is good at winning elections,” said Jack Pitney, a professor of government at California’s Claremont McKenna College. “But he wins elections by making people dislike his opponents. He has never given people a reason to like him.”

Davis might have tried to do that when he ran for reelection in 2002. “Reelection campaigns can be a time for reflection on positive things that were accomplished in the incumbent’s first term,” said Mark Baldassare, research director for the Public Policy Institute of California. But as Baldassare explained, that sort of feel-good message “never took hold” in the negative campaign of 2002. To be fair, the California economy had gone so far south by November 2002 that there was little left for Davis to tout.

In the early days of his administration, the state had been so flush with cash that it could cut taxes and increase services at the same time. But by the time Davis was up for reelection, the dot-com bust, the foundering national economy and California’s disastrous experiment with energy deregulation had changed the state’s economic outlook so dramatically that talk of the good times would have rung hollow.

That’s if anyone would have listened to Davis talk in the first place. While former California Gov. Pete Wilson drew fire for his divisive politics on issues like affirmative action and immigration, Gray Davis has been a unifying force in California: Both Republicans and Democrats find him incredibly distasteful. A poll issued this week by the Public Policy Institute of California showed that 75 percent of likely voters disapprove of the way Davis is handling his job.

While Davis’ policy views are fairly well aligned with most Democrats’, his drab personality and intense focus on fundraising have turned off even those in his own party. Just one example of the disdain and disrespect Davis gets from fellow Democrats: A few days after the November election, one Democratic state senator repeatedly referred to Davis as an “asshole” in a conversation with fellow passengers on a Southwest Airlines flight to Sacramento.

For the Republicans, this makes Davis an irresistible target of opportunity. “Gray Davis has pretty much managed to annoy just about everybody outside his party and a lot of people inside his party — not just because of his policies, but because of his personality,” said Gilliard. “That’s one of the reasons I think this is going to be successful. He doesn’t have a reservoir of support in his own party. If we were in Massachusetts trying to recall a Kennedy or in New York trying to recall Hillary Clinton, it would never work.”

Whether it works in California will depend in large part on what the Democrats do about it. No one — no one — is racing to Davis’ defense just yet. While prominent Democrats have begun to speak out against the recall, they haven’t spoken out in favor of Davis. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, for example, distributed an Op-Ed piece last month urging voters not to sign recall petitions. She warned that a recall would be an expensive distraction and that it could lead to the election of a fringe candidate. She said not a word about Gray Davis and offered not a single reason why he should be governor.

Likewise, the labor groups that are organizing to fight the recall are focused exclusively on the losses their members could suffer if the Republicans take Sacramento — and not the gains they could get if they keep Gray Davis in office.

“We’re not focused on Davis at all at this point,” said Spalding of the California Labor Federation. “We know he’s not popular. All the polls tell us he’s not popular.”

For Davis to win, his supporters in labor and elsewhere will have to do what Davis has done all along — convince voters that, as bad as he may be, he’s better than the alternative. The key to that, of course, is keeping better alternatives out of the race. Davis managed to keep Richard Riordan out of the general election in 2002. Now he must find a way to keep other Democrats from entering the recall race in 2003. If a popular Democrat were to run — say, Feinstein — even Democratic voters would likely vote to recall Davis so that they could replace him with a more savory Democratic candidate.

So far, Davis and the labor groups seem to be succeeding. Representatives of the California Labor Federation met last weekend with Davis and all of the Democrats currently holding statewide elected office. Over the course of the next several days, each of those Democrats announced that he would not seek election in the recall drive. If those commitments hold — and if Feinstein stays out of the race — Davis may survive, if only because Darrell Issa would be so unpalatable for so many Californians.

But there are still wild cards to be played. The Republicans could run a more moderate candidate — someone like Richard Riordan, or perhaps Arnold Schwarzenegger, who has said he wants to be governor of California but just isn’t sure yet when. And then there’s the involvement of the White House. So far, Gilliard says the White House has had no involvement in the recall campaign. That could change soon, and maybe it already has.

Ben Ginsberg, a GOP lawyer instrumental in the Bush vs. Gore litigation, is representing Issa against allegations that his funding of the recall campaign violates federal campaign finance laws. And the Los Angeles Weekly reported this week that Karl Rove has been talking with Republican California state Sen. Jim Brulte about recall-related strategy. (Brulte’s office flatly denied the charge Thursday, saying that Brulte had specifically avoided talking with the White House about the recall to avoid such allegations.)

The biggest mystery out there, though, may be why anyone really would want to serve the remainder of Davis’ term in the first place. California’s budget picture is dire, and whoever is governor will have impossible choices to make. The state’s budget deficit stands today at just over $10 billion. If revenue and spending continue as they are, the deficit will exceed $38 billion by this time next year.

To get the state back into the black, Davis — or whoever is governor — will have to cut services or raise taxes or both. Right now, the Republicans can jam Davis with those choices — and blame him for getting the state in this predicament in the first place. It may not be fair — if Davis is responsible for California’s economic downturn, so too is George W. Bush — but it still will give the White House a chance to demonize the Democratic governor if Bush decides to make a serious play for California in 2004. If Davis is gone, the Republicans may have to take some responsibility for the economic troubles California now faces.

“It’s hard to see how the Republicans in the end really come out ahead in this,” said professor of government Jack Pitney. “If they fall short, then Gray Davis can claim some measure of vindication. If they succeed in recalling him and a Democrat is elected, then they substitute one Democrat for another who is less hated by the electorate, and that makes it harder for them to raise money. And if they win and get a Republican to replace Davis, what do they get then? A Republican governor who has to raise taxes or cut services. Right now, they’ve got the perfect demon in Gray Davis. Why change that?”