Reading Mary Renault's "The Friendly Young Ladies" is like settling down with a warming cup of tea only to find yourself warily wondering if that bitter flavor is the bite of almonds or the sting of cyanide.

Renault's 1944 novel, republished in a Vintage paperback edition, is both sharp and light, a social comedy of sexual identity in which the issue is hardly discussed. Leave those conversations to the dim or doctrinaire, seems to be Renault's attitude. Most famous for her series of novels set in ancient Greece ("The King Must Die," "The Persian Boy" and so on), Renault takes the changeability of sexuality for granted. What may seem like the author's reticence is actually a mark of her sophistication, far beyond the hard and fast boundaries of identity politics.

The era of "The Friendly Young Ladies" -- the novel takes place in 1937 -- had already acquired a nostalgic tinge when the book appeared five years into the Second World War. Its first protagonist is 18-year-old Elsie Vaughan, the sort of shy, fearful girl who you can imagine signing a letter to an agony aunt "Cowed in Cornwall." Elsie, who has dropped out of school, lives with her parents essentially as the pawn in their loveless marriage, and any overture she makes to one is taken as a rebuff by the other. Encouraged by the thoughtless attentions of a young doctor who fancies himself a Casanova of the hand-holding type, Elsie leaves home in search of Leonora, the sister who departed this family tomb nine years earlier.

Elsie had always imagined that her sister was not talked of because she had brought disgrace upon herself by taking off with a young man. She's partly right, but what she's too conventional to see is the book's main joke: Elsie tracks down Leonora -- Leo, as she calls herself -- living in a houseboat in a London suburb with her lover, a bright and pretty nurse named Helen.

Elsie's inability to see the pair's relationship for what it was, according to Lillian Faderman's afterword, was shared by critics of the day. "I could not quite make out what was up with Leonora," said the critic for the English newspaper the Spectator. Though had Elsie been shrewder, she might have been just as confused. Leo and Helen have been together for seven years during which both have taken male lovers (as did Renault and her lifelong partner, Julie Mullard, during the initial years of their relationship). Renault wrote the book partly in response to Radclyffe Hall's lesbian novel "The Well of Loneliness," whose dreary title pretty much summed up what she found so detestable about the book. Neither Leo nor Helen is much affected by guilt nor by the sense that their sexual tastes should settle down on one side of the fence or the other.

You can't quite say that things are shaken up by the presence of the book's two male characters, because in Renault's view, sexuality and all relationships are in flux to begin with. These men -- Peter, Elsie's young doctor (who comes visiting at Elsie's suggestion), and the women's neighbor Joe, a literary novelist whose friendship with Leo is based in the sounding board each provides the other for their work (Leo makes her living writing western pulps under the name Tex O'Hara) -- simply careen into the orbit of these women, and things, however temporarily, rearrange themselves.

The most satirical parts of "The Friendly Young Ladies" are those having to do with Elsie and her parents. They are also the cheapest. None of Renault's observances of Elsie are wrong. She's recognizable as her mother's daughter, the sort of timid girl who, despite her declared taste for adventure, wants things to be nice and comprehensible, and who it is easy to imagine will eventually content herself with secretarial courses and the two-penny lending library before settling down into a dull, approved marriage. But there's an unbecoming superiority to the way Renault writes of the moony, mopish Elsie and the bourgeois vulgarity of her parents that make them convenient and conventional literary slams at the middle class.

Renault is much more successful with Peter, who prides himself on his emancipated view. He believes that the compassion he hands out to women, as easily dispensed as aspirin, makes him something of a cross between a secular saint and God's gift to the female race. His attempted seductions of both Leo and Helen are especially funny because, though he scarcely articulates it, the challenge of impressing his charm upon lesbians strikes part of his boy brain as a challenge worthy of him.

Like that notion of Peter's, the art and the pleasure of Renault's novel lies in what is left unsaid. Faderman points out that Renault's awareness of the limits of what she could have commercially (and probably legally) gotten away with in the '40s dovetails with her natural tendency away from the explicit. And Renault's own afterword, written shortly before she died in 1983, strikes exactly the conservative note Faderman describes. In the afterword Renault takes a disapproving tone toward gay liberation saying, "Congregated homosexuals waving banners are really not conducive to a goodnatured 'Vive la difference!' ... People who do not consider themselves to be, primarily, human beings amongst their fellow humans, deserve to be discriminated against, and ought not to make a meal of it." As politics that's at the very least blinkered. But, as Faderman points out, eschewing self-pity and refusing to make an issue out of different sexuality may be very conducive to art.

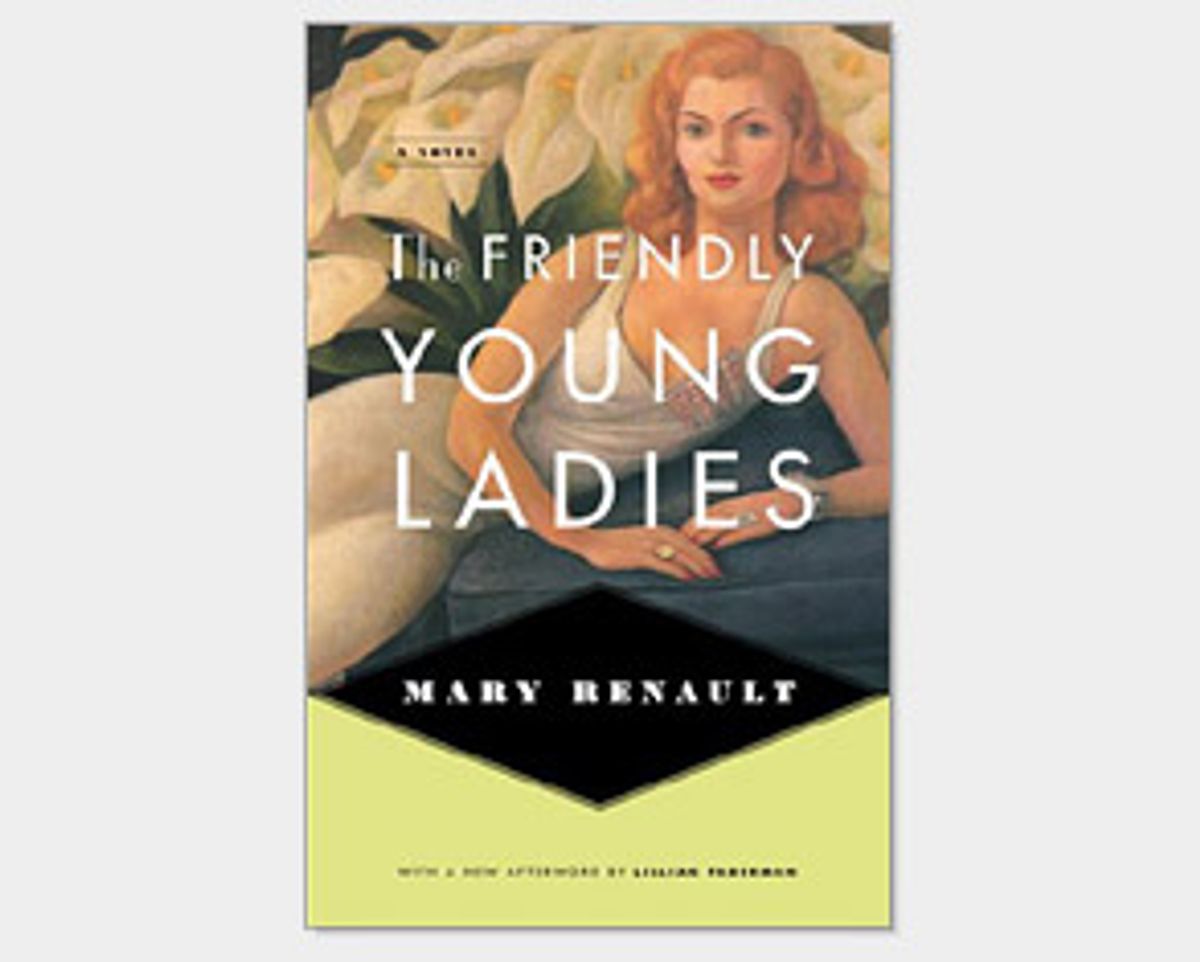

Renault's refusal to spell out what is plain is a way of treating readers who don't understand that Leo and Helen are lovers (or ideologues who insist that they be either lesbian or straight) as unsophisticated party poopers. And her subtle insistence that sexuality is not always a determined thing is a much stronger argument for sexual freedom. "The Friendly Young Ladies" is not a warm book, but its acerbic charm is refreshingly free of sentimental eyewash. And someone at Vintage Books has abetted Renault nicely. The cover of this new edition features Diego Rivera's painting "Natasha Z. Gelman" showing a sleek redhead in an evening gown posed against a soft explosion of lilies. Rivera's immersion in sensuality here is worth every political canvas he ever painted.

Our next pick: An unsettling but mesmerizing tale of tragedy, abuse and art in suburban Boston

Shares