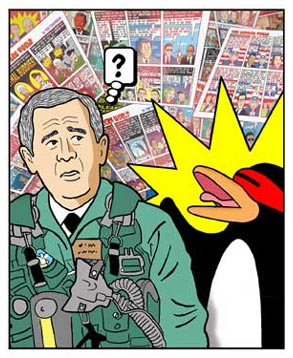

“Who is Tom Tomorrow? It is a question that keeps the public awake at night, tossing and turning throughout the long, restless predawn hours …” So says Tom Tomorrow, anyway, in the amusing, personal foreword to his new book “The Great Big Book of Tomorrow,” an expansive collection of his popular “This Modern World” cartoons. Many of the thousands of Tomorrow fans (and antagonizers) surely have wondered, though, about the man behind the acerbic political and social commentary, the often hilarious takedowns of our venerated leaders and, of course, that masked penguin.

Curious readers won’t be disappointed: In “The Great Big Book of Tomorrow” we even get a picture of the author’s real dog. More importantly, the book is a cohesive, play-by-play of the last two decades’ most consuming controversies broken down and shaken up, typically, into four or six cartoon panels, often featuring those familiar 1950s-retro caricatures. What also distinguishes “This Modern World” from many other cartoons is that they tend to be text-heavy; as “Tom Tomorrow” explained to Salon in a recent interview, he’s happy to take on and dissect the finer points of healthcare plans and trade agreements, not to mention the Bush administration’s increasingly confusing motives for attacking Iraq.

So who is he? Dan Perkins, 42, and a native of Kansas, Detroit and Iowa (he lived in all three before he was 5), first published a serialized version of “This Modern World” in a small magazine while living in San Francisco in the early 1980s. He now lives in Brooklyn and his comic runs in over 100 publications, including Salon. Perkins also maintains his own blog. Recently, he spoke to Salon by phone from his home about being a cartoonist during the Clinton administration vs. the Bush years, why the dead hover over his every comic and why he’s never written a positive cartoon.

You note in the book that your work became more overtly political during the first Gulf War. But what specifically motivated you?

It became explicitly political during the first Gulf War when I was really frustrated that I didn’t have an outlet. Then, suddenly, the little cartoon light bulb went off over my head and I thought, “Oh, I do in fact have a soapbox” and started using it.

Do you remember a turning point?

After one of the big protest marches in San Francisco when there were hundreds of thousands of people marching, it rated about five seconds on the evening news. They immediately cut to a group of half dozen, what in 2003 we would call, Free Republic types, who were protesting in favor of the war. And I just thought, “That’s equal time? That’s extraordinary!”

There’s a great follow-up to this: The local news anchor, who really used to annoy me quite a lot, was meeting with a friend of mine who worked with Project Censored. They got to talking about media bias and the news anchor pulled out his wallet, pulled out a folded up clipping of one of my cartoons and said, “You wanna know who’s biased? This guy is biased!” I thought that was wonderful; of course I am biased. It’s his job not to be biased but it’s equally my job to be completely biased. I get that periodically as a cartoonist — the angry accusation that I’m biased. It’s sort of like saying, “The sun is very bright!” Or, “Air keeps us alive.”

When you became more political, did you enjoy the reactions you were getting? I know you’ve talked about the hate mail that you get.

Feedback is not an unmixed blessing. Especially these days when everyone has a Web site or a blog. There are so many damned opinions out there. It’s just this relentless tide. I’ve reached a point where occasionally it might amuse me and occasionally it might annoy me, but mostly I just don’t care. And it took me a long time to get to that point. I don’t mean to suggest that I’m sitting here in my Zen-like serenity, but when you’ve been out there for a number of years and someone picks up a clump of dirt and throws it at you, after a while you learn to build up barriers and ignore it.

E-mail has made feedback way too easy. Certainly in the early ’90s when people had to write down their thoughts on paper and put it in an envelope and buy a stamp and put it in a mailbox, they really needed to want to say something. They weren’t just going to share some fleeting thought that happened to pass through the back of their mind. E-mail has made it possible to share thoughts that are probably best kept to themselves. I changed the color of the links on my Web site and people wrote in, very angrily — they liked the old color better! One guy said the new color looked too slick and corporate! I don’t mean to disparage the person who wrote that, I’m sure he meant it, but gosh. There are only so many hours in the day.

There also used to be context. When a letter came in and it was in crayon, you had some sense of context. E-mail strips it all away. You have some basic indicators like when someone writes in all caps, or has no sense of grammar or uses terms like LOL for “laugh out loud” — then you know you’re mostly dealing with an idiot. But most of the time it’s hard to know who’s writing this stuff.

During which era did such feedback bother you the most and coming from whom? You’ve been doing this through four presidential administrations at this point.

What bothered me the most was immediately after Sept. 11 when conservatives immediately decided that anyone who did not agree with them on abortions and prayer in school was aligned with the terrorists. The afternoon of Sept. 11, I went online and there were people writing me saying things like, “So you think America deserved this. Well, fuck you!” And I’m thinking, “Hello! What did I say? What did I do?” That really, really pissed me off. I found that shocking, and a little bit frightening, honestly, that there was this undercurrent out there ready to latch on to this. Conservatives just felt that their entire worldview had somehow been vindicated by this event.

I wanted to ask you about your Sept. 11 cartoon — because you didn’t draw one. You used a photograph. Why?

I wasn’t feeling very funny that week. Because it was clearly such a momentous event, such an overwhelming and somber — I’m sorry, I’m just going to sound banal saying this stuff. Everyone reading this interview went through the day also so I don’t need to expand on that. Short answer: I didn’t know what else to do.

Back to what you were saying about bias: One thing that was obvious during the Clinton years is that you really tried to find the ridiculousness on all sides. You could see where your sympathies lay but …

You could see where my sympathies lay, but I pointed out that Clinton was lying about the whole Monica Lewinsky thing straight out of the gate. It was very clear to me many months into the scandal when Clinton supporters were still claiming — as Bush’s supporters are claiming now [about our reasons for going to war with Iraq] — that he didn’t lie. Well, first they were arguing that he didn’t lie at all, that he didn’t do any of it, and then we got into the semantic issues of the meaning of “is.” I guess with Bush we’ve jumped right into the semantic issue. Everyone acknowledges that it was a lie in one form or another. They’re just arguing about the meaning of a lie.

Clinton is more or less the guy on my side of the fence. But I had many, many, many issues with Clinton, and I acknowledged right away that it was pretty clear he was lying. Bush’s supporters should be doing the same thing. Clearly they’re not.

How do you feel that the tone or tenor of your cartoon has changed with this administration? Do you approach Bush’s controversies differently?

The mood of the country changed. You react to what’s going on and to the people in power. During the Clinton years, the cartoon got a little more ethereal. I would be discussing fine points of trade policy or some damn thing like that. My main problem with Clinton was that he sounded good and said a lot of the right things and made all of the liberals feel nice and warm and fuzzy and then went and gutted the social safety net and pushed through trade agreements like NAFTA and GATT [General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade]. His actions often belied his words.

I even detect, I think, a sense of exasperation in your cartoons as though it’s all so obvious to you what’s wrong.

Before, I felt like I was writing about a lot of stuff that I didn’t expect a lot of people to be following — for instance, the ins and outs of the Clinton healthcare plan which was widely smeared as socialized medicine when in fact it was the furthest thing from socialized medicine. The perception was that he was going up against the insurance industry when in fact he had written it with the five largest insurers … Whereas now the things that are wrong are not that complicated.

You also often criticize the media, and usually it’s the television media, but it made me curious where you get your information from in order to write your cartoons. Who do you trust?

Well, um, from the television media? [Laughs.] No, I spend a lot of time reading papers and reading the papers online and watching the news. It’s not a binary either/or situation. I’ve met hardcore left-wing activists who say they simply can’t watch the mainstream media. “I only read Z magazine!” And I say, “Well, then you have absolutely no idea what’s going on in the world.” The information is there, you just have to get it from a lot of different sources, and you have to have some basic understanding of how the world works to decode the ways in which it is presented and come up with your own composite portrait of the world.

The blogs, I have to say, are very helpful because you have a whole army of unpaid researchers digging up all these wonderful nuggets of information.

Any of them that you really like?

Atrios’ site, Daily Kos, Skippy the Bush Kangaroo — they all have silly names. Then again, I’m Tom Tomorrow so I can’t exactly say anything about that. A lot of the sites are the radical center expressing its voice. They seem pretty much to be centrist Democrats but with an anger that you haven’t seen from centrist Democrats in years. That’s a wonderful and healthy development. A lot of my problem with the Democratic Party over the last few years has been the fact that there doesn’t seem to be one.

Do you think they represent or could be the first stages of some kind of shift?

I’m specifically talking about these Web sites. I don’t mean to imply that the Democratic Party is doing anything — they have been taking a nap for a very long time and now it’s sort of stretching and rubbing its eyes and clearing its throat. That’s a good sign because it’s better than being unconscious. But there’s still a way to go.

How do you balance humor and message?

Well, you have certain lines that you’re not going to cross. If I’m going to offend someone I want it to be for the right reason. I don’t want to offend them out of some perceived callousness or disrespect for the dead. Ultimately in these times, the dead hover over every cartoon that you do, whether it’s Sept. 11 or the war in Iraq. So there are topics that I personally try to handle with a delicate touch.

Sometimes I’ll do one that I think is laugh-out-loud funny, and I may be wrong, who knows. But then the week after that one that’s sort of serious. The one I have up today is about how all the stories in favor of the war keep getting rewritten, and it’s not a funny cartoon at all. I think it’s a wry cartoon. It is not only my job to make you laugh out loud; if that were my only purpose in life I would walk around on the street tickling people. But, for example with this cartoon, there were all these stories that kept getting amended, and one hadn’t been mentioned for a while — the looting of the Iraqi museum. The initial reports wildly overstated the damage and then the secondary set of reports wildly understated it. And that was the point at which Andrew Sullivan wrote a column in Salon suggesting that all the liberals who had harped on the wildly overstated damage owed the world an apology. Now it turns out Sullivan wildly understated the damage, though I don’t know if he has issued the world an apology for his mistake. I don’t believe he has.

There was another cartoon that stuck with me — the one whose refrain was “Bomb Iraq.” The first panel was “If you can’t find the guy you’re after — bomb Iraq.”

Right, “What the president has learned in a year since Sept. 11.”

Yes, if you have a problem, bomb Iraq. One of the panels was about Enron. Where did Enron go?

Yeah, that one fell off the map, didn’t it? I really misjudged that one — I thought that would have legs. I don’t know. Where that went was to the back page and the business page. We had a couple of wars. It was pretty much as the cartoon suggested: The president started talking about bombing Iraq and everyone’s attention was drawn away from Enron.

Do you feel more responsibility to what issues you’re grappling with or with what’s in the headlines?

I’ve never really cared about that. And that’s really the big difference between the Bush and Clinton years. More and more I am more likely to be talking about what everyone is talking about because everyone is talking about things that matter. Also, I’m not a daily cartoonist — those guys are getting up in the morning, coming up with the idea, talking to their editors about it, going through the whole process, drawing it, getting it to the copy desk — all in five hours. So they are going to be talking about whatever is on the front page — that’s their job. I have the luxury of going off on tangents. But lately the tangents have been less interesting than the news.

You focus a lot on the evasiveness of this administration. But wasn’t that true during the Clinton administration?

The stakes weren’t as high. The civil liberties situation is terrifying. And the foreign policy situation … this is the most radical presidential administration probably in a century. And unfortunately, it’s trite to say it, but Sept. 11 really did change everything in one important way: It unleashed this administration to pursue its most radical agenda. On the afternoon of Sept. 11, Donald Rumsfeld is sitting in his office writing memos trying to figure out how they can use Sept. 11 to justify attacking Iraq. On Sept. 11, 2001. And there’s a reason for that — Rumsfeld and Wolfowitz and Perle, all those Project for the New American Century guys, have been publicly advocating war with Iraq since the mid ’90s. They issued policy statements saying that we need a foothold in the region that’s more reliable than Saudi Arabia and Iraq is our best opportunity. This has all been out in the open.

Do conservatives accuse you of enjoying all this controversy?

You hear that. It’s beneath contempt. I would happily go back to humorously discussing why Clinton’s trade policy was a mistake in a wacky four-panel cartoon. This is serious stuff. No one is enjoying this. I’m not trying to score debating points, I’m just angry.

I thought it was interesting that in 1992, when Clinton was elected, someone said to you, Well, what will you write about now? as if there wouldn’t be anything to criticize.

Right. There were some dry patches, I’ll admit. I’m afraid we may not get back to that situation for a long time.

Have you ever written positive cartoons?

Oh, come on.

I don’t know. Some moment when you were overcome by a burst of cheerfulness?

It is not a frequent occurrence. But I wouldn’t do what I do if there wasn’t an inherent optimism there. It’s an optimism tinged with bitterness and frustration but if I didn’t believe that things can get better then I would go live in some remote farmhouse somewhere and ignore the world entirely.