On the way into the screening of "Thirteen," I was handed, along with the usual production notes, a sheet headed "A Brief Introduction to the Literature of Being Thirteen." This was an overview of books dealing with the trauma of growing into womanhood in contemporary society, including things like Carol Gilligan's "In a Different Voice" and Mary Pipher's "Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Lives of Adolescent Girls." Was I headed for a movie or a seminar? Either way I was prepared. I took my seat -- quietly, like the good little mouse Gilligan told me I've been conditioned to be -- and procured a pen from my handbag, the better to take notes, just in case there was a quiz later on.

There was no quiz, but I sure got zapped with a killer homework load of teen trauma. There's a tremendous buzz on "Thirteen," the kind of buzz that hums mightily in the ears of socially conscious adults like the after-ring of a Neil Young show. "Thirteen" was itself co-written by a 13-year-old girl, Nikki Reed (she's now 15), who also plays a leading role in the picture. Her co-writer is the movie's director, Catherine Hardwicke, a friend of Reed's; Hardwicke dated Reed's father for a time, and the two stayed close even after the breakup. The critical buzz on the movie seems to follow this line of thinking: If an actual 13-year-old wrote "Thirteen," then it must be realistic.

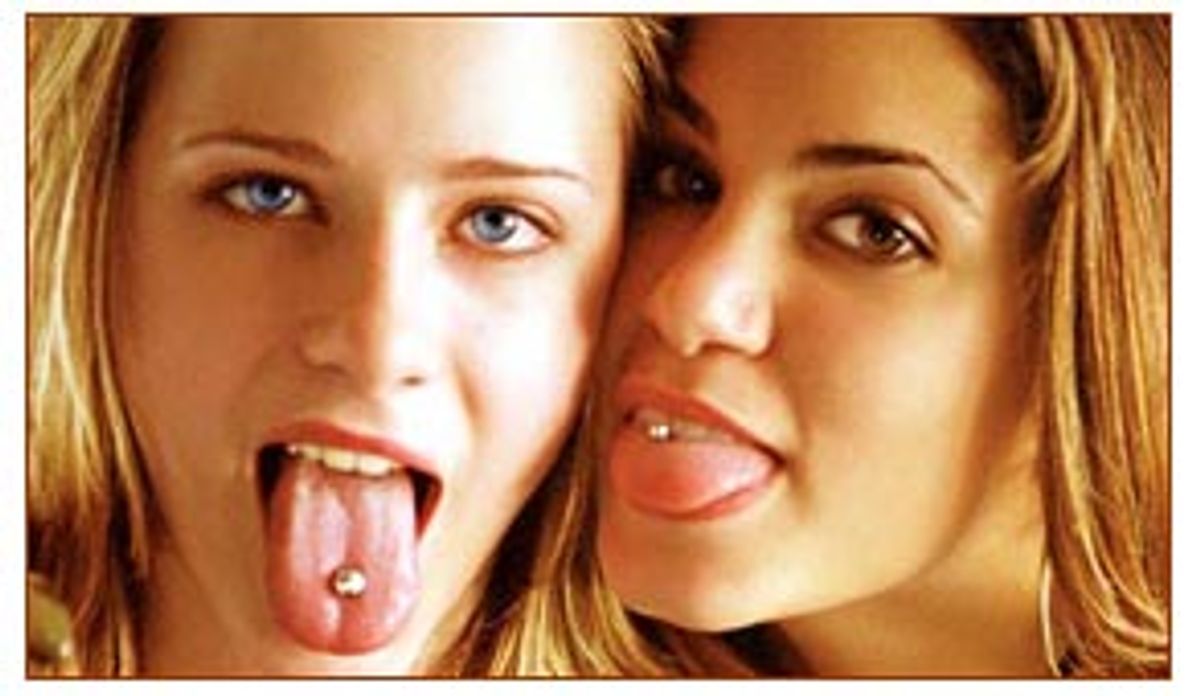

"Thirteen" is a tale of peer pressure, of being just on the cusp of adulthood and yet being expected to act and dress, smoke and drink, like a salacious adult, largely because, as every concerned commentator on youth will tell you, youngsters today are so heavily bombarded with images that they're no longer allowed to be children past the age of 12. At first, bellybuttons and tongues are pierced; silly panties are shoplifted; boys are ogled. Before you know it, drugs are being taken and, worse yet, sold; boys are allowed to touch you there; and parents, even the hippest of them, are shut out with robotic coldness for not understanding this brave and wild new world.

The 13-year-olds in "Thirteen" are Tracy (Evan Rachel Wood) and Evie (Reed). Tracy is a lovely girl with nice cheekbones, honey-blond hair and the body of an insouciant, lazy ballerina; she has not just youth on her side, but bone structure. When we first meet her, with her everyday-girl T-shirts and her basketball sneakers with smiley faces drawn on the capped toes, we think, "She's lovely as she is! She doesn't need a thong or a piercing or a lace-up bustier! She's a beautiful young girl, with everything going for her! Why doesn't she just sign up for the softball team, or make friends with some of those nice debate-team kids?"

And that's precisely how we all step so readily into "Thirteen's" carefully laid trap. Tracy, we learn, does have some serious problems: For one thing, she has a history of self-mutilation. And even beyond that, she, like millions of teenagers everywhere, wants to feel attractive and sexy (and although 13 definitely seems young, unfortunately, there's no magical switch that we can turn on when it has been universally decreed that it's OK for us to feel sexual). Tracy wants all of the trappings -- the thongs, the piercings, the skimpy clothes -- precisely because the coolest, shapeliest, sexiest, most desirable girl at school, Evie, has them all, and more.

Evie is cruel to Tracy at first, in that way only teenage girls can be. She relishes leading Tracy on, making her think she's being friendly, only to turn on her heel and walk off with her much cooler, hipper clique, laughing out loud about everything that's wrong with the way Tracy looks, acts and dresses.

But Tracy wheedles her way into Evie's approval by stealing a walletful of money, which the girls promptly spend at the Steve Madden store, piling up boxes of sneakers and flip-flops with materialistic venom. Evie both remakes and uses Tracy, outfitting her in the right gear, urging her to make out (and more) with boys, enticing her to get high. Evie makes Tracy her partner in crime, and Tracy is all too willing.

Evie, whose guardian is a model/actress/waitress named Brooke (played by Deborah Kara Unger) who lets her drink beer from the fridge (but she can have only one if she's got homework), has some problems of her own. She has no guidance, no boundaries, which makes Tracy's scrambled but loving home life intensely attractive. Tracy's mom, Melanie (Holly Hunter), works as a hairdresser to make ends meet for herself and her family; she's pretty and youthful-looking herself, with her long, loose brown curls and a wardrobe of jeans and tank tops decorated with gothic crosses. She's a recovering alcoholic, so she has her share of adult problems, but she loves her daughter very much, and like a bloodhound (or a vampire), the desperate outsider Evie can smell it. She insinuates herself into Tracy's home life. Like Eddie Haskell in a shredded Juicy Couture T-shirt, she sucks up to Mel, weaving a tale (possibly at least half-truthful) about having been abused both in her youth and, more recently, by Brooke's boyfriend. Evie also reassures Tracy how much she loves her, in a way that's both sisterly and vaguely sexual, all the while enticing her into greater teenage dangers.

At one point, Tracy boards a bus headed for some shopping on Melrose Avenue, and Hardwicke shows us a million and one billboards full of sexy-looking young women and cool things to buy. Look, up in the sky -- images! Images, of course, have been around since the time cavemen learned to draw on a piece of rock with a charred bone, and they've been bombarding us since at least the 1960s. (Prior to that, they used to just limp feebly by, harmless and easily ignored, so teenagers could concentrate on the important things, like soda pop and cashmere sweaters.) But now, they're being catapulted at warp speed, with Britney's thong as the slingshot. Today, 13-year-olds are under more pressure than ever to look and act sexy, to smoke and drink, and to get a boyfriend (or girlfriend) ASAP, just in case that first wrinkle should hit before the age of 16. Since there's no one to blame for this phenomenon, we haul out the images, which have gotten bigger and more potent over the years, as well as, of course, more convenient.

Apparently, both Hardwicke and Reed have heard about the potency of these images, so we shouldn't be surprised that they've hitched "Thirteen" up to its mule power. If "Thirteen" were just a story of a young woman rattled and unmoored by the expectations of her peers, a woman who does bad stuff and makes mistakes like all young human beings are wont to do -- whether they're under bombardment or not -- it might have made for a terrific movie. And in its first half, at least, there are certainly moments that cut to the core of what it must be like to be that age today. I believe that almost anyone who has ever been 13 can remember the sting of not having the right hair, the right clothes, the right details. It doesn't matter whether those details are silk stockings, charm bracelets, maxi dresses or perfectly whiskered jeans: Teenagers, particularly teenage girls, are materialistic beasts, but their desire for the correct totems are painfully understandable. Hardwicke shows that to us early in the movie, in a standoff between the two girls: First we get quick cuts of Tracy's not-quite-right T-shirt, her cheap elastic wristband, her nerdy sneakers. Then we get glimpses of Evie's gleaming silver bellybutton hoop, her low-slung jeans, her tough-girl cross necklace and delicately beaded bracelets. We immediately see why, even though Tracy looks just fine to us, in her world, she's all wrong.

No matter what kinds of pressures today's teenagers are under, the confused two-step of being yourself and fitting in wasn't invented yesterday, and it's not going to go away tomorrow. But by its midpoint, "Thirteen" begins to feel all too much like medicine, and it finally dawned on me why I was given that handout sheet at the beginning: "Thirteen" isn't a story; it's a tract about serious social problems. It's a call to arms, lest those problems worsen. It's a wakeup call to parents everywhere -- though exactly what they're supposed to wake up to, other than a cold sheen of sweat over what their own daughters are either living through right now, or are directly headed for -- isn't quite clear. "Thirteen" is supposed to scare the pants off of you, and not in the good way.

To that end, Hardwicke uses some standard scare tactics. The camera swings around in jerks and starts, ostensibly to replicate the confusion of being 13, or of being seasick -- it's hard to say which. When the story gets really hairy, Hardwicke and cinematographer Elliot Davis switch to grainy, bleached-out film stock, just in case it hasn't dawned on us how desperate Tracy's situation has gotten. You can't fault the actors: Hunter makes a believably hip mom, and you feel for her when Tracy, strung out and pissed off, rails at her for no good reason other than that she's got the mother gene. Wood and Reed both give performances that come off as natural and unforced, which certainly does make "Thirteen" feel more like a documentary than a drama at times.

Which may be exactly the problem. Hardwicke and Reed don't have precise control over their narrative; complex issues (such as Tracy's jealousy over Mel's attentiveness to Evie) are raised and dropped, never to be dealt with again. I guess narrative cohesiveness isn't supposed to matter in a movie that's supposed to be about gritty reality.

So why, then, is Evie's character written like a cross between the conniving Eve Harrington in "All About Eve" and Patty McCormack's pigtailed terror in "The Bad Seed"? We see Evie sneaking out to meet very dangerous boys in the middle of the night (she does an amusing quick-change number, slipping her tube top down around her thighs to turn it into a bandage of a miniskirt); stealing money from Mel's regular-folk hairdo clients; hiding drugs in Tracy's room in order to frame her. Evie is the stuff of great fiction -- if only "Thirteen" would allow itself the freedom, and the power, of being fiction.

So what, exactly, is this thesis of a movie trying to teach us? That being a teenager is different today from what it was 20 or even 10 years ago, and much, much harder? I have no doubt of that -- but I knew it going into "Thirteen," and I don't think I feel any smarter about real teenage life than I did before. All I've really learned is that teenagers are victims of the world around them -- its materialism, its obsession with sex, its messed-up adults -- and that the chances of getting through it reasonably unscathed are slim. Whoops, I did it again, and it's all society's fault. Now there's empowerment for you.

People who go to the cinema to be edified about the Mysteries of Contemporary Society will probably get something out of "Thirteen." But the rest of us might be left asking, What about stories? What about human beings who actually don't behave like hypnotized sheep fulfilling the dire prophecies of a bad sociology textbook? If you boil "Thirteen" down to its flimsy bones, you'll find that it's not really so much about peer pressure in contemporary teen life as it is a story about a classic bad egg. That right there dilutes its highfalutin aspirations. The pressures facing 13-year-olds today are very real. But that doesn't make "Thirteen" a good movie. It's just the latest in the long and proud tradition of pictures that exclaim, with a great deal of hand-wringing, "Kids today!" If only it brought us closer to understanding them.

Shares