In May 2002, Westar Energy sent a $25,000 check to Texans for a Republican Majority, an organization set up to propel Republicans into the Texas state government. What did the Kansas-based Westar care about Texas Republicans? Probably not much. But it did want to curry favor with the political group’s founder, Rep. Tom DeLay, R-Texas, the House majority leader.

DeLay’s “agreement is necessary,” one Westar executive helpfully explained in a memo, according to documents released by the company’s board, “before the House conferees can push the language we have in place in the House bill.”

DeLay took Westar’s money, invited its top brass to a golf gala shortly thereafter, and supported Westar’s language for a lucrative special exemption in the House energy bill. That exemption was ultimately dropped when those in Congress learned of a federal fraud investigation into the company. The bad news for Westar still meant money in the bank for DeLay, and he used the donation, along with many others to Texans for a Republican Majority, to construct the GOP juggernaut that commandeered Texas’ elections. Juiced by DeLay’s cash — Texans for a Republican Majority spent about $1.5 million in the 2002 elections — and organizational prowess, Texas Republicans smothered the opposition. Eighteen out of the 22 Texas House candidates supported by the PAC were victorious, contributing heavily to the GOP’s comfortable 88-62 majority in Austin. Once in power, the Texas GOP — at DeLay’s urging — swiftly got to work trying to gerrymander congressional districts in the Republicans’ favor, even though the districts had just been redrawn two years earlier, based on the most recent census. As that spectacle stands now, 11 Democratic legislators are sequestered in a New Mexico hotel, preventing a quorum on a vote they would surely lose, as the Democratic Party sues to prevent the redistricting, calling it a violation of the U.S. Voting Rights Act.

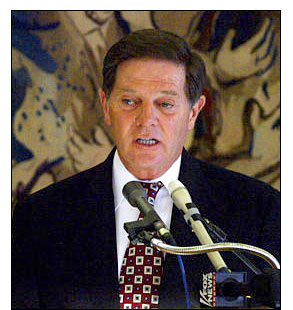

Politically, it was a stunning success for Tom DeLay, perhaps best known as Congress’ most aggressive and outspoken conservative, who steamrolls over anyone who stands in the way of his agenda. What is less well known is that DeLay is also a master of the sometimes dark art of political fundraising. His skill at raising money has helped the GOP maintain its dominance in Congress and has made him perhaps the most feared Texas politician since Lyndon Johnson. But in the 2002 Texas coup, he left behind a muddy trail: A close scrutiny of the money he funneled into the state suggests DeLay may have violated several state laws along the way.

Texas law strictly prohibits campaigns from using corporate donations, and clearly much of Texans for a Republican Majority’s money, such as Westar’s $25,000, came from corporate sources. Jim Ellis, the group’s former director, defends using the corporate money by saying the state rules apply only to organizations directly controlled by labor unions or corporations (a highly disputed reading that, if true, would nullify the point of the law) and that every other similar group in Texas does the same thing — an “everybody does it” excuse that sounds suspiciously like an admission of guilt. Most important, Ellis notes that the organization is split into two groups, a political action committee and a special tax-exempt political group designated a “527” by the IRS. The two organizations are separate, according to Ellis, because the 527 raised corporate money and the PAC raised money only from individuals and distributed that to candidates.

But according to IRS filings, the 527 clearly used its corporate money to organize polls and pay for political consultants, and even Ellis admits that the PAC used those services. Ellis claims this work was merely an allowed “administrative” cost — an expansive reading, given that the Texas Ethics Commission defines “administrative” as “expenses that would be incurred in the normal course of business by any active organization.” Karen Lundquist, executive director of the Texas Ethics Commission, says, “Consulting for the purpose of setting a political strategy is not administrative.” More bluntly, Fred Lewis of the nonpartisan Texas watchdog group Campaigns for People, says, “They are saying a cat is a dog.”

Just as interesting: On Sept. 20, 2002, the 527 arm of Texans for a Republican Majority sent a check for $190,000 to the Republican National Committee’s state arm (RNSEC). That was legal. But exactly two weeks later, on Oct. 4, the RNSEC sent out precisely $190,000 divvied up among seven candidates supported by Texans for Republican Majority, and all received money from it or DeLay’s national PAC, Americans for a Republican Majority, at different points, according to filings with the Texas Ethics Commission. This raises the question of whether TRM, which couldn’t give the money directly to candidates, simply passed the money to the RNSEC. That would certainly be circumventing the law, if not breaking it.

“It comes down to a question of proof,” says Larry Noble, executive director of the Center for Responsive Politics, noting that the legality of such a transaction depends on whether TRM and the RNC had an explicit or even implicit agreement about how the money would be distributed. Noble adds that such a transaction could well be “a way to launder the money and evade the contribution limits.” Ellis denies any connection between the funds. “We gave $190,000 to the RNC. End of story,” he says. “I think the RNC, with their full staff of lawyers, is well equipped to comply with the laws.”

In the middle of this mess sat Tom DeLay, who simply expressed disbelief that anyone would question his actions. “It never ceases to amaze me that people are so cynical they want to tie money to issues, money to bills, money to amendments,” he declared at a press conference in late June.

DeLay has faced similar problems in Washington. There, a large part of DeLay’s method of gaining power was challenged in 2002 by the passage of the McCain-Feingold bill, which banned legislators from raising, using or controlling the unlimited political contributions to political parties or affiliated organizations, commonly known as soft money. Candidates may still accept donations of up to $2,000 from individuals or corporations, but they can no longer snag the $25,000 or $100,000 checks that companies such as Westar used to pony up for soft-money organizations, which the candidates could apply toward indirect campaign expenditures.

DeLay, it seems, may be getting around that ban through an organization called Americans for a Republican Majority (ARM). According to McCain-Feingold, the soft-money wing of that organization is supposed to be completely separate from DeLay. But the congressman and founder, though he has technically spun it off, has maintained extremely close ties even in the months since the new law came into effect. According to documents filed last month with the IRS that cover the first six months of 2003, ARM employs and supports a number of close DeLay allies. It is headquartered at Williams and Jensen, a lobbying firm that signed DeLay’s then chief of staff, Susan Hirschmann, as a partner two months before McCain-Feingold went into effect. ARM has also employed the Alexander Strategy Group this year. That organization was founded in 1997 by a former DeLay chief of staff, Ed Buckham, while he was still working for DeLay. According to DeLay’s 2002 financial disclosure forms, the Alexander Strategy Group also employed DeLay’s wife, Christine, though DeLay spokesman Stuart Roy says that was mainly as a bookkeeping favor for an affiliated organization, which now covers her complete salary.

According to Federal Election Commission spokesman Bob Biersack, it’s not clear how many close ties a congressman can have to an organization he’s supposed to have split from. “There’s no absolute bright line,” he says. But a look at FEC rules shows that DeLay’s relationship to ARM might exceed the coziness that the law allows. According to FEC rules, “candidates, officeholders, and their agents or organizations established, financed, maintained, or controlled by the candidate can’t raise soft money.” To determine whether someone fits the above criteria, the FEC provides a 10-point list that includes “whether the sponsor has any members, officers, or employees, who were members, officers, or employees of the entity that indicates a formal or ongoing relationship.”

Tom DeLay’s relationship with the Alexander Strategy Group and other people and organizations on the ARM payroll seems clearly formal and ongoing, even if his wife is off the payroll. The Center for Responsive Politics’ Larry Noble, a former FEC general counsel, says that whether relationships such as DeLay’s with ARM are allowed to stand “is a battle ongoing right now within the FEC.” “The game that they are playing is they say that these people no longer work for DeLay and that they have no common membership,” says Noble. “The reality is that they are setting these groups up with people who have long experience and who can definitely parallel what the office holder is doing, and who other people know are connected to the office holder.” Again, DeLay may not face any consequences. According to Craig Holman of the watchdog group Public Citizen, “I believe DeLay is violating the rules. But I also believe the FEC has no backbone.” Both Democrats and Republicans have stacked that organization with people who are hostile to campaign-finance reform. Moreover, as Rep. Barney Frank, D-Mass., points out, people think that all politicians break the rules when it comes to money. Thus, the Democrats might be seen as saying DeLay should be reprimanded because he does it worse. “It’s hard to make the quantitative argument ‘This man is twice as bad as me so he should go to jail,'” Frank says.

The influence of money and politics can make even DeLay’s charitable intentions appear unseemly, however. Last April, the majority leader held a golf tournament in Key Largo, Fla., to benefit his foundation for foster children, the DeLay Foundation for Kids. The tournament offered bigwigs the chance to amble around the links with powerful Republican congressmen such as Roy Blunt, DeLay’s chief whip and sidekick. Mimicking a standard political fundraiser, the foundation solicited funds from a motley collection of supporters: one “platinum”-level donor giving $100,000; 25 “crystal” donors giving $10,000.

The tournament sold out. And why shouldn’t it? Corporations got to give money to DeLay without disclosing it, while receiving both face time with congressmen and tax deductions to boot. To make attracting star power easier, DeLay successfully worked just before the tournament to overturn Congress’ rules preventing charities from paying for representatives’ travel.

Past brochures offered sponsors the opportunity to display their logos at the course’s most prominent holes, and donors included corporations such as AT&T, which gave $25,000 in 2001 and 2002 — about the same amount of money it gave to both Americans for a Republican Majority and Texans for a Republican Majority. According to currently filed tax returns available through GuideStar, no other nonprofit foundations have given to the DeLay Foundation for Kids.

But this isn’t a normal foster-child foundation and the event wasn’t organized like a normal bake sale. The firm handling the fundraising, the DCI group, was simultaneously representing the Burmese junta in its efforts to rebut reports that its army used rape as an instrument of governance in areas controlled by ethnic minorities. That’s not to say DeLay does not care deeply about foster children, and he will no doubt spend the raised money on their behalf. He and his wife have taken in three foster children in years past and even his political opponents credit him for his sustained passion on the issue. But it’s just a typical example of how DeLay’s life seems dominated by the close relationships to the businesses that keeps him politically so unstoppable.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

As a young adult coming of age in Texas, DeLay’s life roughly parallels that of the president he now serves. Kicked out of Baylor University for partying too much, he graduated from the University of Houston in 1970. Along the way, he drew a low number in the Vietnam draft lottery, skipped the war, and then started a pest-control company. He was elected to the Texas State Legislature in 1978 and to Congress to represent his Houston suburb in 1984. Soon after arriving in Washington, he entered a period where, he told the Washington Post in 2001, he drank “8, 10, 12 martinis a night,” before finding a deeper Christianity. According to that same Post profile, he cut off all contact with his two brothers, sister and mother, an issue his press secretary refused to discuss. Mostly, since climbing on the wagon, DeLay has fixated on winning power for conservative Republicans.

As he’s gained experience, DeLay has simply become more effective, making him every Republican’s best friend, worst enemy, and financial lifeline. He is particularly adept on Capitol Hill at a technique called “catch and release.” If a crucial vote comes up where moderate Republicans find themselves opposing the conservative GOP leadership, DeLay and his golfing partner Blunt corral them in the back of the House chambers. If it becomes clear that DeLay’s side will win anyway, the moderates are released to vote their or their constituents’ conscience. If the vote appears headed against DeLay, he twists the moderates’ arms into voting with him.

DeLay can play this game because he knows the moderates fear him. In 1995, Republicans abolished the old system conferring committee chairs based on seniority. Instead, the leadership started deciding who got to serve as chairs. This is why moderate Rep. Christopher Shays, R-Conn., who generally supports DeLay, was blocked from becoming chair of the Government Reform Committee, a move even he says he knew would be a consequence of his support for campaign-finance reform. Rep. Marge Roukema, R-N.J., simply left Congress after DeLay boxed her out of several positions. In several primaries, DeLay has also worked against several moderate Republicans in favor of less electable conservatives, showing that the Texan would sometimes rather lose with a conservative than win with a moderate. DeLay has yet to support a challenger to a moderate incumbent, but before last November’s elections, DeLay gave money to the Club for Growth, a powerful Republican group that spent most of the winter attacking Republican moderates who didn’t support Bush’s full tax cut.

He’s capable of much deeper grudges. According to a story broken by Roll Call, the representative once diverted $70,000 into a Texas sheriff’s race and commissioned push polls against one of the candidates apparently because the candidate made the mistake of hiring the wife of a man whose business partnership with DeLay had soured and wound up in court.

DeLay is also loyal — not just to politicians who vote with him, but to his staffers, many of whom work for him for a few years and then move into lucrative lobbying jobs. When the Hill listed the city’s top lobbyists, four were former DeLay employees. No other member of the House was credited with having more than one alumnus. Three of these alums are connected with ARM and the fourth, Drew Maloney, hasn’t really left the family. Five of his clients at the Federalist Group gave at least $30,000 to DeLay’s different fundraising organizations between January 2000 and December 2002. One of them, Reliant Energy, gave $75,000 to DeLay and, according to Roll Call, its Washington office last year hosted the baby shower of DeLay’s daughter, Danielle Ferro, who has done heavy fundraising for Texans for a Republican Majority. Roy says, “It’s always useful to have people both on the political side and lobbying who still consider themselves part of the organization and looking out for DeLay’s best interest.”

All that has helped DeLay obtain astonishing results, firming up conservative control of all levers in the House and getting moderates to back him when it counts. Consequently, he routinely wins by tiny margins on votes he’s expected to lose. In June, he won a crucial vote on Medicare by one vote. Then in late July, DeLay ripped a homer to deep right field by winning a vote on Head Start — kicking some funding responsibility for that early-education program back to state governments — by a margin of 217-216. Rep. Dick Gephardt, D-Mo., missed the vote while traveling. The one-vote margin gave rise to a mini backlash against one presidential candidate who would surely have opposed the bill. DeLay had outfoxed the Democrats again

The extreme positions DeLay stakes out, and his propensity for outlandish rhetoric, make it easy to portray him as an ideological fruitcake. He has, after all, blamed the teaching of evolution for the massacres at Columbine high school, compared the Environmental Protection Agency to the Gestapo, and once allowed a petrochemical lobbyist named Gordon Gooch to actually write legislation. Speaking of liberals on the House floor earlier this year, DeLay said, “Their malignant hold over the intellectual life of this country must be exorcised, and men and women who are willing to speak the truth offer our only hope of reclaiming our culture from the grip of a hedonistic, reckless and destructive descent into nihilism.”

DeLay’s extremism has made some Democrats hopeful that DeLay might eventually instigate a split in the Republican Party, perhaps pushing a few Jim Jeffordsesque moderates into the Democratic fold or creating a general backlash against the party and President Bush. That hasn’t happened yet, and DeLay has only occasionally sparred with the White House. He quashed Bush’s request to distribute his gigantic tax cuts slightly more evenly, declaring that “ain’t gonna happen” when Bush asked that Congress change the tax bill to include a bigger credit to low-income families. He also took a trip to Israel in July and delivered an extraordinarily inflammatory speech the day after Bush met with Ariel Sharon. Addressing Israel’s parliament, DeLay declared his opposition to a Palestinian state and said, “You’ve got to change a generation before you can have a peaceful state that can live side by side with Israel.”

Still, Bush and DeLay have yet to really clash, and neither has given hints that they will. In fact, if DeLay has done anything to Bush, it has been to make the president appear more moderate than he really is, a potentially calculated service as Bush tries to tack back to the center in time for the 2004 elections.

Some liberals also hold out hope that DeLay will fracture the Republicans’ Christian base with his often-unbecoming fundraising, particularly from quarters that religious conservatives scorn. DeLay and his close confidantes, for example, have raised lots of money from gambling interests — a lobby at odds with the religious right. But still, his fundraising seems to have caused few rifts. “I appreciate the difficulty of good people in difficult positions,” says Tom Minnery, vice president of public policy of Focus on the Family. Says Phyllis Schlafly, president of the Eagle Forum, “His job is to get conservative bills through the legislature, and he is very good at what he does.”

The Democrats’ other, perhaps wistful, hope is that DeLay will ultimately step on one of his own land mines, like the Republican House leader he once served under, Newt Gingrich. The two do share a propensity for saying the outlandish. But Gingrich seemed much more self-serving: worrying as much about getting airtime as managing his revolution, managing an affair with a Hill staffer (now his wife) during the Clinton impeachment mess, and trying to cash in on his power with a book deal. DeLay seems simply concerned about accumulating as much power as possible for himself and the conservative wing of his party, and he’s done a much better job than Gingrich at making sure that his bills become law. “The ethical attacks on DeLay have been about money that he has raised for his cause,” says Barney Frank, the Massachusetts representative. “Gingrich’s ethical problems had to do with the enrichment of Gingrich.”

“Gingrich swung for the bleachers every time,” says Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform. Most famously, in 1996, Gingrich grumbled to reporters that Clinton ignored him on Air Force One during flights to and from Israel for the funeral of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, even forcing him to exit the plane from the back. Gingrich went so far as to suggest that Clinton’s rudeness kept House Republicans from compromising on a budget resolution — which caused a government shutdown and idled 800,000 workers. “Cry baby!” cried the front page of the New York Daily News, complete with an illustration of Gingrich in diapers. It was a P.R. disaster. A similar snafu from DeLay seems far more unlikely. Instead of pouting to the press about exiting Air Force One from the rear, DeLay probably would have just quietly removed the plane’s engine.