Next to the Hong Kong action picture “So Close,” nearly every Hollywood thriller of the summer looks like an elementary-school project thrown together the Sunday night before it was due. Director Corey Yuen’s work here is fast, exciting and, above all, clean. One of the best action directors in the world, Yuen never sacrifices precision for speed — although at times the pace of the movie is incredibly fast — and he has an infallible sense of camera placement. (He’s aided by Keung Kwok Man’s sleek cinematography and Ka-Fai Cheung’s razor-sharp editing.) Even in the midst of the fastest-moving sequences, you’re always able to tell exactly what’s going on. At its giddiest “So Close” is both exhilarating and relaxing. The kinetic thrill of the individual sequences carries you along, yet within each of those sequences you see things with the clarity of those moments when time seems to stretch out before you.

It may be that after a string of turkeys like “The Hulk,” “The Matrix Reloaded,” “Bad Boys II” and “S.W.A.T.,” “So Close” seems like a bigger deal than it is. A terrific Hong Kong thriller like “So Close” doesn’t offer the character development or the moral ambiguity that still distinguishes classic American westerns and noirs. You won’t find the equivalents of “Red River” or “Out of the Past” in Hong Kong cinema. And you won’t find the equivalents of the adult entertainments that Hollywood sometimes still manages to make (often despite audience indifference), pictures like “The Russia House,” “Out of Sight” and “Devil in a Blue Dress.”

It’s possible for some critics and fans to get so caught up in the pleasures of Hong Kong movies that they forget that movies can be more than thrillers or fight scenes. But Hong Kong movies are, on the whole, the best examples now being made of what movies so often are. American audiences no longer have the luxury, as audiences during the studio era did, of taking competence for granted in the detective stories and westerns and comedies that were the staples of their moviegoing. In the studio era, even the worst hack director could tell a story clearly. But now, most of the time American commercial movies make no narrative sense and no visual sense; action scenes have been reduced to a blur, spectacle without any attempt to make clear the physical relations between anyone or anything. When it comes to fulfilling the function of filmmakers as entertainers, Hong Kong moviemakers have been putting most of their American counterparts to shame since the mid-’80s.

There’s been some intermittent starry-eyed babble about “the innocence” of Hong Kong moviemaking. Hong Kong movies are calculated commercial enterprises and, at times, they’re crass in ways that American movies have thankfully abandoned. The worst kind of fag-baiting humor still rears its head (as in Ringo Lam’s latest film, “Looking for Mister Perfect”), and eroticized rapes still happen in some action movies (as in Wong Jing’s recent, incredibly brutal “Naked Weapon”). But even when they are brutal, and even though they have started to develop some self-reflexiveness (parodied in Johnny To and Ka-Fai Wai’s recent “Fulltime Killer”), they continue to seem refreshingly free of cynicism.

The most familiar genres don’t yet seem played out in Hong Kong movies because the filmmakers have not stooped to treating audiences as if they were no more than wallets to be picked. The filmmakers believe that audiences have not outgrown their capacity to be astonished, or their capacity to feel. Pomo irony has not touched Hong Kong movies, which are blessedly unashamed of sentiment. There’s a moment in “So Close” where a character is symbolically laid to rest by the burial of a video camera playing images of the character still alive and happy. It’s one of those corny touches that shouldn’t work, that sounds irredeemably sappy on paper; and yet, in execution, it becomes one of those moments that only the movies are capable of giving us, a moment that seems so natural that it becomes almost cleansed of calculation.

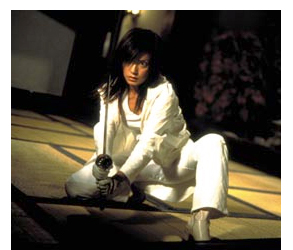

There’s plenty of astonishment in “So Close.” In the opening sequence, the luscious Shu Qi, as Lynn, one of the movie’s pair of sister hitwomen, pushes herself back from an executive’s death through a slo-mo shower of crystalline shards of glass and, before you’ve quite registered what’s happening, is hanging upside down from the ceiling, dispatching the villain’s henchmen with a handgun. Here, as in much of the movie, Yuen adds a comic poetry to the violence so you laugh as you gasp. This is followed by Lynn making her way out of the villain’s headquarters, kneecapping baddies as she goes, while her sister Sue (Zhao Wei) monitors Lynn’s progress on a computer and provides a soundtrack for the shootings: the Carpenters’ “Close to You” (heard in a sound-alike version). This great perverse joke doesn’t stop Yuen from using the song later for a romantic interlude.

That sort of quicksilver switch of moods — from brutal action to romance to physical comedy — can discombobulate some Western viewers. Or it can seem the delightful inclusion of every crowd-pleasing element movies have to offer as they suit Yuen’s whim.

The plot of “So Close” is about how Lynn and Sue, who started their hitwomen business to avenge their murdered parents, wind up being the prey when they’re double-crossed by a treacherous corporate hotshot who hired them. Kong, a cop played by Karen Mok, is also on their trail. And there’s a romantic interest, Lynn’s long-lost summer love Yan (Seung-heon Song) who comes back into her life.

As is typical with Hong Kong movies, the plot is both complicated and peripheral. (If you go see “So Close” you should know that the subtitles are, for the first few minutes, hard to read. They rapidly become more visible.) It’s really an excuse for Yuen to execute one virtuoso action sequence after another. That’s the genuine excitement of his movies (as it was in his last picture, the nifty “Transporter”). In one scene, Lynn and Sue switch places, with Sue going to do the job while Lynn guides her escape from their computer bank. It’s a knockout, with Sue getting split-second warnings before making hair’s-breadth moves with her getaway car.

The gadgets in this movie are doozies — Prada heels that emit four-inch spikes, allowing the wearer to hang from the ceiling; sunglasses that contain cyanide capsules. It’s as if Q had been asked to devise a fall line for Vogue. (The white pantsuit Shu wears in the first scene is particularly fashion-forward.) Part of the fun of “So Close” is getting to see Shu, who’s been pretty much used as eye candy in her previous roles, getting to take part in some physical action. She seems more alive here than she has in some of her previous films.

It would be wrong to pretend that “So Close” adds up to more than a superior piece of action-movie craftsmanship. Enthusing overmuch about Hong Kong movies can bring you perilously close to sounding like the young French movie critic in “Irma Vep,” who uses action movies to crow over the death of “personal” cinema. But it would be equally wrong to suggest that the appeal of a movie like “So Close” is the triumph of movie machismo.

While mainstream Hollywood movies have continued to become processed and pat and shoddy, Hong Kong movies have kept the craft and pleasure of mainstream movies alive. “So Close” doesn’t represent the best Hong Kong cinema has to offer. It doesn’t approach the fantastic quality of something like Tsui Hark’s “Swordsman II” or the hallucinogenic delirium of Clarence Fok’s “Naked Killer” (now out on domestic DVD and not to be believed until seen). “So Close” might just be an enjoyably cheesy evening out for the occasional moviegoer. And it may seem like junk to film connoisseurs. But the pleasure of this kind of sharp craftsmanship is its own justification. And for constant moviegoers (and critics belong in that group), the precision and thrills, the sexy charm of Shu and Zhao, Corey Yuen’s ability to deliver the action-movie goods without making you feel like your brain is turning to jelly or you’re taking part in some sleazy ritual, are reminders that some of the most basic pleasures — a plot that makes sense, stars that are allowed to be stars, the visceral excitement of a tightly constructed chase or fight — can no longer be taken for granted.

There’s nothing here of the poetry you see in some martial arts fantasies where the characters soar through the air. But watching fashion plate Shu hang from that ceiling while firing a gun, or seeing Zhao execute impossible moves in Hong Kong traffic, has some of the same pleasure, the pleasure of seeing the laws of gravity and physics gleefully defied. King Kong was only 18 inches tall, and Fred Astaire didn’t really dance on the ceiling. (Jackie Chan, on the other hand, really did jump from the side of a cliff onto a hot-air balloon.) But the movies would be poorer if we didn’t believe that Kong was a behemoth and Fred Astaire could glide on the breeze if he took a notion to. In its small way, “So Close,” and the Hong Kong cinema it represents, make you believe in the movies as the place where the impossible looks easy.