When I was 17, I worked at the Gap for about two weeks. During that time, I heard "Papa Was a Rolling Stone" approximately 48 times. I was repeatedly encouraged to foist matching red socks on those purchasing red shirts, and to apprehend any woman looking at the Levis in order to "get her into our Gap Jean." My manager, who loathed me for reasons I could not understand, would instruct me to "straighten up the north wall," which was perplexing not just because I didn't generally carry a compass, but because the store was usually empty and didn't need straightening.

One day, while I was refolding a massive stack of mock turtlenecks, one of my adult co-workers crept up and stage-whispered, "I think she's shoplifting!" gesturing to a very large, very mean-looking woman with a big purse. The co-worker stood there, clearly expecting me, a skinny teenager, to confront and possibly detain this glowering suspect. Later, my manager reprimanded me for refusing to put my life on the line, explaining that such trouble was out of my adult co-worker's jurisdiction, since she was, in theory, foisting matching socks at the front counter. I'd like to say that I quit right then and there, but pathetically enough, I coaxed my mom to call and quit for me the next day. (Thanks, Mommy!) To this day, though, the opening strains of "Papa Was a Rolling Stone" can hurl me into an existential abyss that knows no bounds.

When we hear about high suicide rates and depression among young people, we shake our heads in disbelief, picturing a nation of miniature Andy Roddicks and Britney Spearses worrying their pretty little heads over nothing. The way America mythologizes the shiny successes of youth culture, it's easy to forget the painful zits, the pointless, sadistic school projects, the psychological abuse of sociopathic teachers, the endless string of torturous low-level jobs that once made a life of prostitution and hard drugs look really attractive by comparison.

As popular as self-deprecation has become among bloggers and unconventional essayists, most Americans rarely revisit their missteps and mistakes, choosing instead to focus on the times they triumphed over setbacks. We, in turn, teach our kids an elaborate lie about pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps when, in fact, most of us greeted the major disappointments of our young lives by whining and freaking out and receding into a debilitating, indecisive fog.

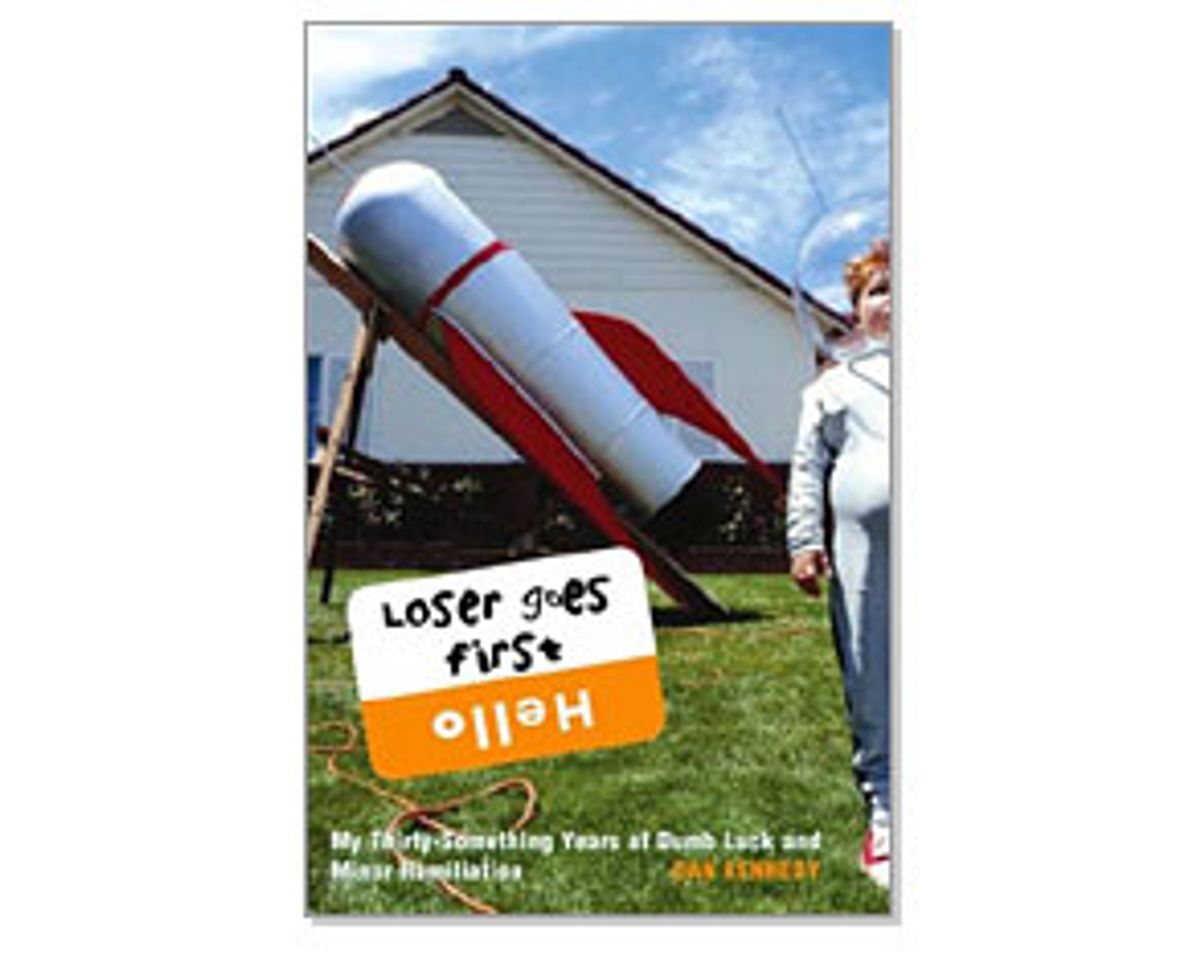

If, by erasing our missteps, we're engaging in an elaborate ritual of denial that impairs our ability to empathize with the young and the less fortunate, then Dan Kennedy's new memoir, "Loser Goes First," should be mandatory reading for potential parents, government officials and teenagers alike. Despite his current successes -- Kennedy is director of creative development at Atlantic Records and a contributor to McSweeney's and Bookforum -- the author drags out a long history of the most embarrassing sorts of mistakes and parades them around for our amusement.

Kennedy isn't simply indulging in the self-flogging voice that's hip at the moment. In fact, he shelves his ego completely, dredging up absolute catastrophes without flinching or hedging or couching it all in self-consciousness or padding it with "I already know that you know that I know" footnotes like fellow McSweeneyan Dave Eggers. Despite the rambling, slightly scrappy nature of his narrative, Kennedy's utter lack of excuses, posturing or pretense gives "Loser Goes First" a trustworthy, likable voice and make it a fascinating read for anyone who gets a perverse thrill from reading about someone else's crappy decisions.

Luckily for Kennedy, he seems to have an inexhaustible ability to crawl out of dead-end situations and throw himself into new pursuits, whether it's bass fishing or songwriting or owning an espresso franchise. He may be gullible, negative and a major quitter, but he always emerges with some appreciation of his experience, a few fresh insights into what he wants from life and an absurd story (or 12).

After living with his parents and working at a local warehouse, Kennedy starts training to be a firefighter, mostly because this girl he knows is doing it. A slight, somewhat lazy kid, he finds himself unexpectedly relishing the harsh physical training and boot-camp conditions: "The good part about being on the side of a mountain freezing your ass off and swinging some kind of ax thing called a Pulaski while guys scream the same things at you from the outside that you've been screaming at yourself from the inside your whole life is this: There is no TV to watch, no bar to go to to ignore it, no three-to-nine-month girlfriend to tell you to just go to sleep, and no junk food or junk sex to lust and eat."

But the moment Kennedy pinpoints the benefits of any one career or hobby, he's already moved on to something else. After describing the excitement of fighting real fires, he quickly admits that, instead of getting into it and maybe even looking forward to the next fire season, "All I was thinking was, A hundred dollars a day before taxes? This is a rip-off. I should try something else. Maybe be a songwriter or something."

Kennedy's honesty is admirable, and it makes him a humble but sure-footed storyteller. His description of performing at an open-mike night in Austin, Texas, is unforgettable. Armed with bad guitar skills, a bunch of distortion pedals and a notebook of rambling suggestions for possible lyrics, Kennedy tanks dramatically, in front of an audience of musicians, their mandolins and violins in tow. More than being disgusted or annoyed, the crowd looks at him "as if I'm their little brother or their son and it's just kind of cute that I even got up there and tried."

After relocating to Seattle -- just in time to miss the bad-guitar-and-distortion explosion there -- Kennedy is brutally honest about his reasons for wanting to become a counterperson at an espresso cafe. He imagines that such types are generally "sort of leftist, vaguely well-traveled underachievers with a neo-hippie influence and a solid catalog of '70s pop culture references ... This job would make me cooler and no longer quite the misfit. Instead I would seem like a misfit by choice, plus somehow smarter than you about government and art and things like that."

An undeniably entertaining writer, Kennedy offers a backstage tour of every pose and clumsy maneuver in his history, and combines a flair for creative adjectives, a litany of pop-culture references and amusing digressions to make the frustrations and absurd twists of his experience feel utterly palpable. Once you get used to the meandering pace of his prose, his vivid descriptions nicely capture those intense moments of powerlessness when your oppressors become larger than life. His boss at the espresso cafe, for one, was prone to springing surprise tests on his employee. Kennedy reports that it was easy to tell when such a test was coming because his boss would "wear that pressurized little grin that is supposed to convey good cheer, but when mixed with his trademark stress and almost amphetamine congeniality, looks more like a sitcom version of Jack Nicholson in 'The Shining.' It looks like the grin of a confused jackal or a pestered coyote, or of an uncle resentfully attending a family cookout that took him away from a horse race or a hooker, but since nobody in the family really knows about horse races or hookers, he just sits there with the consolation prize of Coors beer and hamburgers, acting happy to see you ... that kind of grin." Ah, yes. We know that grin.

Like any humorist, Kennedy exaggerates, and at times his actions and ideas are so unbelievably dense, it's tough to accept that such a sharp writer could have been quite so confused. His dimwit tone works fairly well on the whole, though, and the odd lists and strange jokes scattered throughout the book are a lot of fun. This from "A Few of the Lies I've Told You as an Advertising Copywriter": "Your children would rather have other parents based solely on the fact that you aren't serving meals that are as fun as the meals being served by your neighbors, but if you purchased these frozen meals, your family would be somehow better and more fun, like the neighbors whom your kids love more than you."

Sometimes Kennedy fancies himself as awfully cute. Sometimes he wanders into roundabout jokes that are hard to follow and not all that amusing. But considering the hipster drivel you might expect from a book with the subtitle "My Thirty-Something Years of Dumb Luck and Minor Humiliation" -- a book you might be likely to loathe, sight unseen, out of sheer boredom with the self-flogging, snarky voice of the moment -- "Loser Goes First" is irresistibly weird and brave and satisfying. Most of all, though, it will make you damn glad that you're no longer forced to fold mock turtlenecks and confront felons, while listening to the soul-crushing strains of "Papa Was a Rolling Stone" one more time.

Shares