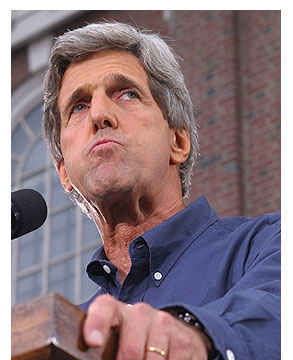

When John Kerry lost his voice at two crucial moments early in the Democratic presidential primary race — during the first Democratic debate in South Carolina in May and again at the AFL-CIO candidates forum in August — it was hard not to see his hoarseness as a metaphor for his troubled campaign. Howard Dean had seized the lead in Iowa and New Hampshire and was making headlines as the grass-roots favorite who could harness the outrage of the party’s base and ride it to the nomination. Kerry was having a hard time projecting his complex message above the pro-Dean din.

Now, a month after his last bout with voicelessness, Kerry supporters are insisting their candidate has found himself and is coming on strong with a new amped-up appeal. A new TV spot declares that the man who fought in Vietnam and then led antiwar protests can bring the same “courage” to providing “affordable healthcare, rolling back tax cuts for the wealthy, really investing in our kids.” With Kerry accused of being programmed and passionless, the spot begins with film footage of arguably his most memorable political moment, as a recently returned veteran asking the Senate Foreign Relations Committee: “How do you ask a man to be the last man to die in Vietnam?”

But Kerry’s new message is in danger of being drowned out by the excitement surrounding retired Gen. Wesley Clark, who announced his candidacy Wednesday, as well as static from his own troubled campaign, whose talented but top-heavy staff is squabbling over whether to bash Dean or take a more statesmanlike approach.

Clark’s candidacy is bad news for all the Democratic contenders, but especially for Kerry, who can no longer say he is the only candidate with the credibility on national security that comes from military service. The interest in Clark, which ranges from New York Rep. Charles Rangel to influential labor leader Gerald McEntee (who had earlier hinted that he supported Kerry) to members of former President Bill Clinton’s inner circle (and perhaps the former president himself), suggests that Democrats want to run a more compelling version of the war hero Kerry for president — or balance a nominee other than Kerry with a vice presidential candidate who has experience defending the nation. Maybe most important, Clark’s dramatic entry into the race increasingly has the media treating the nomination battle as a two-man contest between Clark and Dean, with other candidates, including Kerry, mere also-rans.

Meanwhile, Kerry communications director Chris Lehane resigned Monday, and his departure attracted attention to disarray within Kerry’s campaign. Current and former Kerry associates describe different fault lines — Senate staffers vs. campaign staffers; newer Washington-based staffers and consultants vs. older Boston friends; liberal populists vs. “New Democrat” centrists; and even, sometimes, the candidate and his wife, the outspoken Teresa Heinz Kerry (both Kerrys, for instance, have publicly lamented not running TV ads sooner, in order to head off Dean), against Kerry’s staff.

More staff changes are expected soon, but time is running out on efforts to reorganize the campaign. Kerry has few remaining chances to get his message across and attract the undivided attention of the Democratic activists who dominate early party caucuses and primaries. He didn’t stand out in recent Democratic debates in Baltimore and Albuquerque, N.M., where the news was Connecticut Sen. Joe Lieberman’s attacks on Dean. And he was less well-received than Dean, former House Democratic leader Dick Gephardt, and North Carolina Sen. John Edwards in a joint appearance at a conference of the largest AFL-CIO union, the 1.5 million-member Service Employees International Union.

Kerry got a small bounce after he relaunched his campaign early this month with a formal announcement of his candidacy and a four-state tour, taking the lead in two separate national polls conducted by Time/CNN and Fox News. He continues to attract endorsements from leading Democrats, including California Sen. Diane Feinstein, who announced her support Tuesday.

But the Massachusetts senator still trails the former Vermont governor 38 percent to 26 percent in a Boston Globe poll of New Hampshire Democrats, whose early primary is likely to leave the losing New Englander injured or eliminated from the race for the presidential nomination. And lately Kerry has been attracting new and not always positive attention for his campaign’s recent barrage of e-mail to journalists attacking Dean for his statements about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, his reversal of his support for free trade agreements, and his unsurprising rejection of an invitation from Kerry to debate one-on-one.

“We’ve noticed for months, but the media is only catching up recently, that Howard Dean has taken different positions about different issues at different times,” said the Kerry campaign’s press secretary, Robert Gibbs. “It’s fair game.”

Kerry’s campaign wasn’t expected to go like this, especially after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, when he seemed to be the strongest candidate the Democrats could field against President Bush. A Vietnam veteran who had earned a Bronze Star and three Silver Stars, a former county prosecutor, and a four-term senator with a liberal voting record and expertise on foreign policy, national defense, and combating terrorism and drug trafficking, Kerry seemed the sort of tough-minded progressive who could rally Democrats in the primaries and reach out to swing voters in the general election.

Moreover, Kerry had the reputation as a skilled infighter who came from behind to win Democratic primaries for lieutenant governor in 1982 and U.S. senator in 1984. He kept his Senate seat against the popular Republican Gov. William Weld in 1996, with the two former prosecutors debating eight times. Many Democratic activists eagerly awaited the devastating counterpunch that the war hero Kerry would deliver against Republicans with no combat experience, including Bush and Vice President Cheney, if they ever dared to question his patriotism.

So why hasn’t Kerry caught fire? He has suffered from his muted, muddled message, confused by a campaign that airs its disagreements in public, and his own patrician reserve. Many observers think his manner has only become more subdued after his recovery from prostate cancer earlier this year, although he insists he feels fine and made a full recovery.

At a time of war and recession, core Democrats’ twin passions are peace and populism. But Kerry is no longer seen as a peace activist, and he never was a populist.

Even before the Iraq war began, Kerry became one of its first political casualties. Together with Lieberman, Gephardt, and another presidential contender, North Carolina Sen. John Edwards (who formally announced his presidential candidacy Tuesday), Kerry voted for the congressional resolution authorizing military action in Iraq.

But Kerry, whom many still remember as a leader of Vietnam Veterans Against the War, paid the highest price among Democratic activists. “If Kerry had opposed the war, he would have had the entire Democratic left behind him,” said Jeff Faux, who recently retired as president of the liberal Economic Policy Institute. “With his war record and moderate style to appeal to the centrists, and a desire by the money people to unite early against Bush, he could have been closing in on the nomination by now.”

Instead, Dean became the only leading contender to oppose the war. He soared, and Kerry sagged. But more than antiwar sentiment was at work. “The essence of the Dean message wasn’t antiwar, it was anti-Bush,” explained Robert Borosage, co-director of the liberal Campaign for America’s Future. “It was that Dean was willing to speak out against Bush, and the others weren’t. The Washington-based candidates, including Kerry, didn’t understand how furious Democrats were with Bush and how much they wanted someone who would express fury at his policies, how he had stolen the election, and what he was doing to the country.”

While Kerry was expected to be a peace candidate, populism has always been alien to him. From a patrician background and now a multimillionaire-by-marriage, Kerry doesn’t bash big business, as Edwards does, or boast of devoting his career to the cause of working families, as Gephardt does.

Former advisors recall that he rejected populist appeals in his reelection campaign in 1996, even though polling showed that it would have been popular to berate profitable corporations for laying off employees. This year, too, his domestic policy positions are complex and nuanced. He calls for repealing Bush’s tax cuts for the wealthy but not those, such as the children’s tax credit and the elimination of the marriage penalty, that benefit the middle class. And he proposed expanding health insurance through a less costly and comprehensive program than those proposed by Gephardt and Dean.

While these positions have popular appeal, especially in the general election, they don’t lend themselves to sound bites and bumper stickers. Kerry’s campaign has had a hard time framing and focusing his message. In interviews with advisors, staffers and supporters, no two offered the same answer to the question: “Tell me Kerry’s message in one or two sentences.”

A leading advisor explains Kerry’s appeal this way: “Bush has taken the country radically in the wrong direction. This is not just a series of policy mistakes but is driven by a vision that is fundamentally wrong — a radical vision that is at odds with America’s principles and 200 years of our history.

“This is a more fundamental and more basic critique of Bush than Dean has offered,” the advisor continued. “Dean focuses on the Iraq war. Kerry’s critique applies across the board to an economic policy that puts wealth in the hands of a few and a foreign policy that abandons alliances we have worked decades to build.”

Meanwhile, Kerry’s chief speechwriter, Andrei Cherny, rattles off a riff on Kerry’s patriotic populism: “We now have a government that hasn’t measured up to the American people’s courage and sense of optimism about the future. John Kerry will bring that sense of courage and forward-looking optimism to the White House.”

The complexity of Kerry’s message, and the lack of agreement among his advisors and staff about what it is, reflect the feuding and factionalism within his campaign.

In the latest headline-making family quarrel, communications director Chris Lehane resigned, amid reports that his draft for a Dean-bashing announcement speech had been rejected by the candidate and his media advisor, Bob Shrum.

In fact, the quotable, combative Lehane, who issued a statement wishing Kerry well, may have been looking for a way out of the campaign, so that he could devote all his time to a lucrative consulting business whose clients include the effort against recalling California Gov. Gray Davis. Based in California, Lehane had worked without pay for Kerry and decided not to move to Washington, D.C, to take a full-time salaried job with the campaign. While Kerry and Shrum were the principle authors of Kerry’s announcement speech, a longtime Boston political observer maintains that several of Lehane’s lines did find their way into the text. Meanwhile, Lehane’s business partner, Mark Fabiani, has been helping Clark launch his candidacy.

With Lehane’s departure, Shrum is clearly calling the shots on Kerry’s message. A former wordsmith for Massachusetts senior Sen. Edward Kennedy, Shrum has orchestrated hard-hitting campaigns for clients ranging from Kennedy and Kerry to former Maryland Gov. Parris Glendening, the late California Sen. Alan Cranston, and the late Pennsylvania Gov. Robert Casey. Shrum helped craft populist appeals for two of Kerry’s current rivals — Edwards in his 1998 campaign for senator and Gephardt in his 1988 run for the presidential nomination — and counseled Al Gore to adopt a similar theme (“the people against the powerful”) in the last lap of his presidential campaign in 2000.

Now Shrum seems to have synthesized a message that melds populism with Kerry’s patriotism and the New Democrats’ emphasis on the middle class. In the weeks ahead, the campaign will criticize Bush for failing to ask the wealthiest Americans to contribute to their country in a time of crisis, while differentiating Kerry from Dean and Gephardt, who want to eliminate recent tax cuts for the middle class as well as wipe out those for the wealthy.

This message began to emerge as Kerry’s announcement address, delivered the day after Labor Day, retooled the stump speech he’d delivered for the past year. Unusually lengthy and substantive for an announcement address — “denser and more intricate than it had to be,” in the judgment of Boston political consultant Dan Payne — Kerry’s speech still had many memorable lines that he could use with great effect in TV spots, candidate debates and campaign appearances.

Attacking Bush’s premature photo-op finale to the Iraq war, Kerry offered this surefire applause line: “Being flown to an aircraft carrier and saying, ‘Mission accomplished,’ doesn’t end a war.” Recalling that he served in and marched against an earlier war, he declared: “Protest is patriotic.” Segueing to “patriotic patriotism,” Kerry criticized Bush for glorifying “a creed of greed” that “comforts the comfortable at the expense of ordinary Americans” and “lets corporations do as they please.”

Why did it take Kerry so long to craft a message, take to the airwaves, and spread the word in cyberspace? Different cliques in the candidate’s circle of friends, advisors and staff offer strikingly similar critiques of the campaign.

For most of the past two years, Kerry’s campaign was “troubled by an inside-the-Beltway view of the world” that was “preoccupied by his biography” and “did not understand the depth” of rank-and-file Democrats’ “resentments of Bush,” declared one political activist who has known Kerry for more than 30 years. “His own instinct was to oppose the war, but they [Kerry’s Senate staff] talked him out of it,” this Kerry confidant continued.

Other longtime Kerry associates blame the campaign staff for not being tough enough on Bush and Dean, for failing to tell Kerry to his face to be more plain-spoken and less policy-wonkish, and for shutting them out of strategy sessions.

Significantly, of all the Democratic presidential campaigns, only Kerry’s is publicly mired in internal quarrels, although Gephardt, Edwards and Graham are also running behind earlier expectations. With the exception of Dean’s campaign manager, Joe Trippi, only Kerry’s campaign has what one Massachusetts political operative calls “celebrity consultants,” who may be eager to preserve their reputations, whatever the outcome. And Kerry also suffers from Massachusetts’ distinctive political culture, with its long memories, deep pessimism and biting wit. Just as Boston baseball fans are used to watching the Red Sox lose pennant races, Massachusetts political hands are accustomed to seeing local heroes, from Edward Kennedy to Michael Dukakis and Paul Tsongas, stumble when they reach for the presidency. So, while other candidates have hometown cheering sections, Kerry faces a chorus of kibbitzers, eager to explain to the national press why their state’s latest standard-bearer is no John F. Kennedy.

Before Labor Day, rumors were rife that Kerry would shake up his campaign staff, perhaps replacing or demoting campaign manager Jim Jordan, a former executive director of the Democratic Senate Campaign Committee. Over the past two weeks, Kerry has alternately encouraged and denied these rumors while two opportunities passed by to shake up his staff without risking reports that his campaign was in disarray. His relaunch would have been an appropriate moment to announce new staff, and the commemorations of Sept. 11 might have overshadowed campaign news.

Now, Kerry campaign press secretary Gibbs says that the campaign will not have “unplanned changes,” such as replacing current staffers with new ones, but instead will “continue to add staff and grow, as campaigns do.” Lehane’s departure creates an opening for a new communications director, likely to be congenial to Shrum. And, since the campaign still does not have a chair — usually a part-time position filled by a political veteran — Kerry could place a senior strategist above Jordan. The most-mentioned possibility is John Sasso, who managed Dukakis’ successful campaigns for governor, planned his presidential run, and returned during the final weeks of the 1988 campaign when Dukakis gained ground. Sasso turned down Kerry’s offer to manage his presidential campaign but might accept a call for help similar to Dukakis’ pleas in October 1988. Another prospect is Boston political consultant John Marttila, whose clients have included Delaware Sen. Joseph Biden and former New York City Mayor David Dinkins.

But layering in new staff might further confuse a campaign that already double-teams key roles, with two media firms (Shrum, Devine and Donilon, and Greer, Margolis, and Mitchell) and two pollsters (Boston’s Tom Kiley and Washington’s Mark Mellman).

Still, the pre-mortems on Kerry may be premature. He continues to have enormous potential — as a candidate, and as a president.

Former Kerry speechwriter Bill Woodward remembers the senator as “intellectually curious,” interested in talking through complex positions on issues such as affirmative action and education reform. Former Clinton White House aide Minyon Moore recalls: “When the president invited senators to talk policy in his residence, Kerry always stood out. His depth, his knowledge of policy issues, his thoughtful line of questioning was always thorough and impressive. I said, at that time, This guy can be president.”

But, to become president, Kerry will have to be more persuasive, and that means finding the voice he had years ago.

Long before Clark or Dean were well known, Kerry was seen as an eloquent orator, with a commanding presence. “When he was younger, he was a speaker of style and grace,” recalls University of Massachusetts journalism professor Ralph Whitehead. “He modeled himself after President Kennedy. Since then, the country has changed, the culture has changed, public discussion has become coarser, and Kerry seems frozen in time.”

Recently, while Kerry’s message has been shaping up, he has been loosening up. In a New Hampshire diner, he choked up with tears after a jobless mother told him about the hard times she’s suffered. Several days later, he jammed on the guitar with the rock musician Moby.

But what he needs, most of all, is to communicate outrage and answers not only about an increasingly unpopular involvement in Iraq but also about unemployment, stagnant wages, shrinking health coverage, plundered pension plans, and other crises confronting working Americans.

A Kerry friend since the early 1970s, Marco Trbovich says, almost wistfully: “Kerry has a powerful sense of injustice.” But that moral passion is something Kerry has yet to communicate in this campaign.

As his TV spot recalls, Kerry has spoken powerfully in the past. As a 27-year-old former Navy swift boat commander, recently returned from Vietnam, and without advisors and staff, Kerry eloquently and memorably told a Senate committee: “How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?”

If Kerry finds the voice he had as a younger man, the former front-runner could be a contender again.