At moments, watching the superb new documentary “Morning Sun” (now playing at Film Forum in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston) suggests what it might be like to see atrocities rendered as oil paintings on black velvet. Two of the directors of this film about Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, which aimed to rid China of Western capitalist influences, Carma Hinton and Richard Gordon, are the team that made the great 1995 documentary “The Gate of Heavenly Peace” (Geremie R. Barmé is the third director here). Hinton was born in China in 1949, the year Mao came to power, and lived there until 1969, and that may have much to do with the amazing access the filmmakers have to archival material and to the key figures who are interviewed.

Even though the century just past accustomed us to the grotesque lies of totalitarian propaganda as they appear in newsreel footage and “official” newspapers, the monstrous kitsch that recurs throughout “Morning Sun” to glorify Mao’s rise and justify the mass denunciations and killings of the Cultural Revolution is flabbergasting. When you see footage of the 1964 musical extravaganza “The East Is Red” staged at the Great Hall of the People to celebrate the 15th year of Mao’s rule, you feel like you’ve fallen down the proverbial rabbit hole. Remember those Hollywood musicals that climaxed with a big stage show so massive we realized it could never take place in an actual theater? “The East Is Red” is that big, and we’re seeing it acted out in front of an audience. An entire Communist choir stands to one side of the stage while seemingly hundreds of performers move across it, acting out moments from Mao’s quest to rule China. The singers step forward to perform numbers whose lyrics all appear to have been taken from Mao’s doggerel poems or aphorisms.

Seeing the hearty smiles on their bland, confident faces is like having the most homogenized strain of American movie musicals reflected back at us in a sinister new form. It’s what you might expect to see if Angela Lansbury had been triumphant at the end of “The Manchurian Candidate” and staged the inaugural ball as a celebration of the Chinese Communist struggle. When ballerinas in Mao outfits sprint, en pointe, across a woodland set, we’re watching something that might have been produced by Metro Goldwyn Mao: “Seven Red Guard Soldiers for Seven Reactionary Counterrevolutionaries.”

History as spectacle — as predetermined narrative, as performance — is the controlling metaphor of “Morning Sun.” What plays out before us is a tale of the acceptance of mass delusion and mass hysteria. Mao, under unexpected criticism because the economic policies of the Great Leap Forward had been so disastrous, blamed those who worried about the mass starvation with being more concerned with economics than politics, with wanting to dilute a pure socialist state and open itself to imperialist/materialist/Western influence. What he proposed was an upheaval that would purge the very minds and culture of China, that would admit only the socialist purity he wanted, in which any recidivism would be a cause for public denunciation. First to go was Western literature and music and performances. Then, Communist Party officials themselves. His most useful tool was the young, especially the university students wanting to fulfill their revolutionary potential, even if it meant disowning or denouncing teachers, family members, friends.

So “Morning Sun” becomes a sort of a fairy tale, a story of children (Chinese youth and university students) coming under the influence of an all-powerful wizard (Mao), except that in this version the wizard is the good guy. Listen to the lexicon of Maoist iconography: the Long March, the Great Leap Forward, the Great Hall of the People. It’s mythomaniacal language designed to propagate its own legend. The propaganda musicals and dramas we see produced by the Chinese film industry (one in particular, in which a working-class boy’s materialist corruption is foretold by his admiring the cut of a new jacket) are as leaden and grotesque as you might imagine. In the context of the movie, they cut deeper than the newsreel footage narrated by a chirruping female voice proclaiming the greatness of Mao. (That’s some feat, considering that one of the newsreels we see tells how a school of deaf children had their hearing restored by coming to understand the philosophy of their beloved leader. I’m not making this up.)

The footage has that effect because we are watching the story of people who took such shallow, banal things as signals for revolutionary action, which meant public denunciations followed by exile, public beatings and execution — millions died in the Cultural Revolution. It all illustrates one of the contradictions of Communism: the way Marxist ideology, which is anti-religious, morphed in its official version into its own religion, inspiring a crusading fervor few modern religions achieve.

Interspersed among the footage are interviews with the people who slipped the confines of the fairy tale Mao was imposing on China. They include the student founder of the Red Guard, Luo Xiaohai, who became appalled at the violence the Cultural Revolution inspired; Song Binbin, whose name, meaning “gentle and refined,” was rechristened by the press “Song Be Militant” when Mao said to her, “Better be militant”; Li Nanyang, who struggled for years to prove herself a good communist, even rejecting her father, Li Rui, a former party official who was disgraced after denouncing the economic policies of the Great Leap Forward; and Wang Guangmei and Liu Ting, respectively the daughter and widow of President Liu Shaoqi. In exile and in poor health, he was kept alive for the Ninth Party Congress in 1969 to prove the existence of enemies to the state and allowed to die of pneumonia shortly thereafter. Liu Ting was publicly ridiculed and denounced during the Cultural Revolution (we see film of her dressed in a humiliating costume before students who heap abuse on her) and jailed for many years.

These people speak as those who have awakened from a bad dream. Maybe one of the reasons they agreed to be interviewed for the film is that they have all been wronged themselves. That doesn’t mean they appear before us to let themselves off the hook. You never get the sense, as you do listening to some of the collaborators in Marcel Ophüls’ Holocaust documentary “The Sorrow and the Pity,” that they’re trying to cover their tracks or substituting justification for explanation of their actions. You do sense people who existed in a nation swept up into a fever dream, where resistance meant at best incredible hardship, and quite possibly death — not just for them but for their families as well. Because all of the interviewees are so thoughtful and eloquent, we get a sense of how hard it was for them to suppress their doubts, and of the guilt those doubts caused them — the suspicion that they themselves were backsliders.

The tension playing itself out in “Morning Sun” (the title comes from Mao’s dictum that the young are like the morning sun, “the hope of the future”) is the tension present in any revolution between inclusion — the belief that revolution will sweep everyone into supporting it — and the desire to maintain purity. One of the interviewees, Yu Luowen, had an older brother, Yu Luoke, who wrote an essay saying that the children of “bad families,” in other words, the families deemed reactionary or capitalist, had as much right as anyone else to take part in the revolution. The essay won initial approval. What revolutionary doesn’t want to believe that anyone can be won over by a revolution’s truth? But “Morning Sun” shows how attitudes were mercurial, and Yu Luoke was arrested and shot. Luowen tells us that when soldiers came to inform his father what had happened, he reacted in disgust to see his father break down wailing. Li Nanyang relates an incident declaring to her classmates the infraction of calling her father, deemed an enemy of the state, “Dad.”

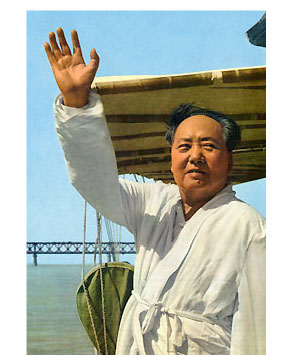

Mao, whose visage seen throughout the movie is that of a fat, sedentary tomcat who’d scratch your eyes out at the slightest provocation, was the only father any child obeyed during the Cultural Revolution, and “Morning Sun” shows how the Revolution was the strongest expression of the cult of personality that surrounded him. His purging of many Communist Party officials was an obvious move to consolidate his power. But it also had the purity of revolutionary logic — that is, the purity of something ready to eat itself alive. Disobedience to the party was a crime, unless it was disobedience or questioning of those whom Mao had branded traitors to the Revolution.

It would be enough if Hinton, Barmé and Gordon had made a movie that is consistently lucid, one that supplies all the information you need at any given moment. They are also among the most humane of documentarians, never pushing their interviewees, allowing them the space to present themselves, extending them the empathy of understanding how easy it was to get caught up in Mao’s crusade. And they manage the trick of making their films aesthetically pleasing without blunting their force as historical, human or political documents. There’s a brilliant section here intercutting a scene from “The East Is Red” with the same incident dramatized in a propaganda film. It’s the most concise expression of this film’s sensibility — the sense that real life, real history, has gone into hiding, and only representations can be compared.

“Morning Sun” ends abruptly, with a few lines of narration setting out the paradox Mao represents for China: He is an ever-present image who stands for past tyranny but also for the possibility of rebellion. Whether that rebellion will be for good or another outburst of the nightmare of the Cultural Revolution, the filmmakers cannot say. The story they are telling here is still in the process of being written. It’s as good a sign as any of how absorbing “Morning Sun” is that the film’s sudden ending makes you greedy for more, for the balance of discernment and empathy that is their gift to contemporary documentary filmmaking.