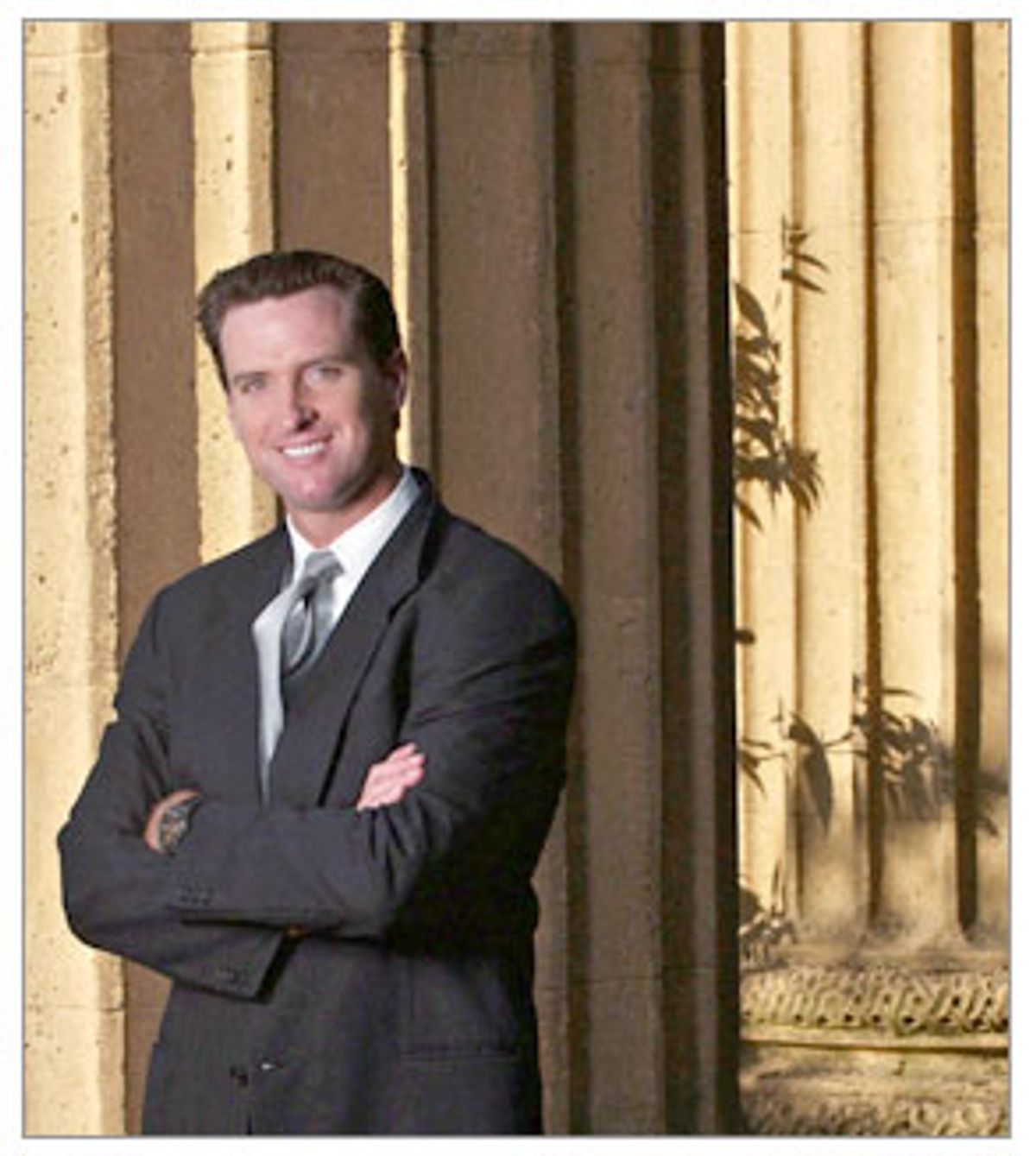

Moments before San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown delivered his final State of the City address Tuesday morning in the glorious City Hall rotunda, its gilt-trimmed arches glinting in the autumn sunlight, tall, dark and beleaguered Supervisor Gavin Newsom swept in from a side entrance and eased his lanky, well-clothed frame into a front-row center seat. Lately it's looking like Newsom, who's been endorsed by Brown, will have a harder time sweeping into the mayor's office when his patron vacates it in January.

Despite Brown's backing and a $2.4 million war chest; despite sponsoring a homeless-aid reform ballot measure last year that won almost 60 percent of the vote and -- briefly -- made him look invincible; despite a sprawling, well-oiled field operation that spent more on payroll taxes last quarter than two leading candidates managed to raise in the same period; despite youth -- he's 36 -- money, good looks, some good ideas and the support of a wide swath of the city's rich and famous (and some regular folk too), Newsom is stuck in the polls at around 35 percent, leading the pack of mayoral wannabes by a sizable margin but nowhere near the 50 percent plus one he'd need to avoid a runoff. So next Tuesday's election is just a prequel to set up the real race, between Newsom and whoever finishes second. But now the December runoff, which used to seem like a formality on the way to Newsom's inaugural, is shaping up to be a fierce battle between the moderate Newsom -- who'd be a liberal in most cities but who's savaged as a right-winger here -- and whichever left-leaning candidate is still standing after Tuesday's election -- if the lefties haven't torn each another apart by then, that is.

"I've done three different polls and they had three different candidates coming in second," says veteran pollster David Binder, who's working for business groups and ballot initiative sponsors, not a mayoral campaign. "The race for second is clearly tightening." It's clear that nobody -- including Newsom -- has yet assured a majority of voters he or she can revitalize the city after the tech bust, solve its grim homeless crisis, shore up its flagging tourist trade or force its warring ethnic groups to get along. This is by far the nation's most liberal city, says Rich DeLeon, San Francisco State University urban politics expert, "but even on the left there's a strong strand of civic pride. People want this to be a city of greatness, and they want a mayor who can rev the city up again." So far, no candidate quite seems up to the challenge.

The struggle for second place, and for the right to wear the mantle of the left into battle with Newsom, is bad news for Supervisor Tom Ammiano, who ran an amazing last-minute write-in campaign against Brown in 1999, riding a wave of anger at dot-com gentrification -- remember young white tech lords evicting whole families from Mission District flats? -- getting roughly 49,000 votes and forcing the lordly incumbent into an unexpected runoff, which Brown won. Ammiano's been the left's presumptive standard-bearer ever since.

But then former Supervisor Angela Alioto jumped in and split labor, while Treasurer Susan Leal, a liberal Latina lesbian, challenged Ammiano's appeal as the gay candidate. And in August, on the eve of the mayoral campaign filing deadline, Ammiano backer, Board of Supervisors president and Green Party leader Matt Gonzalez stunned the city, and many of his friends, by diving into the race, insisting that while he'd endorsed Ammiano early, he'd come to the conclusion that the former teacher, stand-up comedian, gay rights leader and school board member simply couldn't beat Newsom. The first time I talked to Gonzalez about his decision, just after he declared, he told me it wasn't about Ammiano's politics. "I'm not running because Tom isn't progressive enough," said the 38-year-old Gonzalez, a good-looking, bass-playing, former public defender of Latino descent who's got a neo-Beat appeal. "I'm telling people, if you like Tom and you think he can win, vote for him."

That was then. A couple of weeks ago the Green leader sent out The Mailer That Shook the Mayor's Race, comparing himself, Ammiano and Newsom, and concluding that Ammiano, the dean of the local left, was closer to Newsom, its favorite whipping boy, than to Gonzalez. Ammiano allies went ballistic. "The left is split and angry," longtime gay activist Robert Haaland wrote in a bitter, widely circulated e-mail. "The mailer ... is just more evidence of that bloodbath that has occurred ... At the end of the day, the ends of Matt's campaign do not justify the means."

Now it's a nasty free-for-all. "I feel bad for Tom," says Angela Alioto. "I mean, when is Gonzalez going to start attacking Gavin Newsom? All he's done is bash Tom." If you believe Alioto feels bad for Ammiano, she's got a pretty red bridge to Marin she'd like to sell you. In recent weeks Alioto's sashayed past the brawling lefty men to win key endorsements that Ammiano took for granted, including from unions and the city's oldest alternative newspaper, the San Francisco Bay Guardian. (The Guardian endorsement was mainly the handiwork of publisher Bruce Brugmann, who overruled angry Ammiano and Gonzalez lovers on his staff, proving that freedom of even the alternative press belongs to those who own one.) According to many polls, Alioto and Gonzalez are now vying for the No. 2 spot, while the flagging Ammiano campaign, running out of money, fights to stay relevant, and Susan Leal, who still has a sizable war chest, fights to stay alive. (Republican former police chief Tony Ribera has no chance -- some think he's just setting up to run for supervisor on the west side of the city against board conservative Tony Hall -- nor do a handful of lesser-known candidates.)

As if that wasn't enough turmoil on the left, Gonzalez backer Supervisor Chris Daly threw a hand grenade into the race last week when, while serving as acting mayor during a Brown trip to Asia, he used his mostly ceremonial power to appoint two supporters to vacant posts on the city's powerful Public Utilities Commission, bypassing two Brown appointees who were awaiting swearing-in. If Gonzalez is the local left's cool theoretician, detached and intellectual, Daly is its mad bomber, a 31-year-old whose first act as supervisor was to get into a shouting match with the mayor (who's 38 years his senior) that almost turned physical. Daly's brazen PUC move was either a sign that the left is feeling its oats, or that chaos begets chaos, or maybe both, but one thing is clear: The reign of Mayor Brown is about to be over, and no one has a clue what comes next.

That's particularly true on the left, where the Gonzalez campaign raises the question of whether the Green Party is the left's future or its undoing. Critics say Gonzalez is playing trademark Green politics, savaging a progressive ally and, inadvertently, making way for someone more conservative. But his supporters insist he came along in the nick of time, to energize a coalition of the disaffected, breathe new life into the race and "stop the coronation of Gavin Newsom," in Gonzalez's words, in the coming election.

The scholar of the local left, Rich DeLeon, isn't so sure. "I have this creepy déjà vu feeling that it's 1991 all over again," DeLeon says. That's the last time the San Francisco left self-destructed, turning on its former champion, then-mayor Art Agnos, for the crime of compromising with the business community on development during an economic downturn and not stroking enough tender lefty ego in his contentious four years as mayor. Alioto ran against Agnos ("I have no regrets about that," she told me this week. "He closed a health clinic I cared about") but that time around the Bay Guardian (whose clip-and-take-to-the-polls voting guide delivers lots of lefty votes) endorsed former Sheriff Richard Hongisto. An out-of-his-league pro-business police chief, Frank Jordan, squeaked into the mayor's office while the lefties squabbled. (He squeaked out four years later, defeated by Willie Brown.) "I'm a Green Party member myself, and I admire Matt Gonzalez," says DeLeon. "But the question is did he move too soon, and risk dividing, not uniting, progressives?"

So if it's 1991 all over again, does that make Newsom Frank Jordan? DeLeon's not mean enough to float that comparison. But clearly the surprise of the mayor's race is how vulnerable a candidate Newsom is turning out to be. Right now, though, they all look a little like Frank Jordan: flawed candidates who, even if they win, won't win, exactly; it's more like they'll be the only one standing when the others lose. The question hovering above the race is who can be trusted to run this troubled "city of greatness," in DeLeon's formulation. I change my mind every day, and I'm sure I'm not alone.

Listening to Brown's last big speech in the majestic City Hall rotunda -- which the mayor restored either as a great gift to the people of San Francisco, according to his backers, or as a $300 million monument to himself, in the eyes of detractors, who used to call it the "Taj Ma Willie" -- it was hard not to notice that a political era was passing, but a new one hasn't yet dawned. It's a little bit dark politically in San Francisco right now.

Love him or hate him, Brown rescued the city from the Lilliputians of local government in 1995, uniting a coalition of labor and downtown business, blacks, gays and Asians, neighborhoods and developers. Then he ran San Francisco the only way he knew how: imperially, with a populist twist, as a last hurrah for a certain kind of old-time municipal machine. He knocked heads to end planning gridlock and pushed through stalled development projects. The rich got richer, including some of his friends, but he shared the wealth for a while by expanding the city's payroll and presiding over the great dot-com boom.

He'll be remembered for presiding over that boom -- and bust -- and for unapologetically backing pro-development policies that awakened the slumbering left four years ago. His most important legacy may be remaking the waterfront, yet the gorgeous Embarcadero rings a still-troubled downtown, where sad, sick homeless folks and sometimes-menacing panhandlers run rampant. Still, even though I've criticized Brown over the years, I find myself thinking this fractured city is going to miss his hand on the rudder, not to mention his role in pulling together our warring tribes with his charisma and singular racial appeal. Once his coalition united blacks and Asians; now they're squabbling bitterly. The ugliest battle in the city isn't the mayor's race but the fight over how students are assigned to public schools -- specifically whether school assignments should promote diversity by sending kids to far-off neighborhoods, or favor kids who live close to their schools. And school-board Greens are joining Chinese parents, many of whom are conservative, who are angry at having to send their kids across town to integrate academically weak black-and-Latino-dominated schools, in trying to topple the imperious but capable African-American superintendent, Arlene Ackerman. Ackerman is backed by Brown, but it's not clear even Brown can save her.

The mayor's State of the City speech Tuesday offered a snapshot of the looming leadership vacuum. There was Brown behind a lectern, on the landing of the graceful central stairway, while the supervisors sat below him like impish schoolboys (and they are virtually all boys: District elections, which were supposed to usher in new, progressive, representative city government, just happened to bring in 10 men, all but two of them white, and one black woman, Sophie Maxwell). Newsom sat quietly in the center -- he's the good schoolboy -- while to the mayor's left the impish Daly and Gonzalez whispered to one another and fidgeted, as Tom Ammiano sat beside them, smiling and making nice with everybody. Ammiano has tried to take the young left's revolt against him in stride. "Yeah, I'm angry, but I don't have time to be angry," he told me shortly after Gonzalez declared. "I get their impatience. I'm 61, they're all in their 30s. It's the father thing -- and I'm sure they always wanted a gay, queenie father." One of Ammiano's problems with appearing mayoral is that he's almost pathologically nice; no one fears him. But none of his rivals have gravitas, either; Gonzalez probably could, except he shuns such old-fashioned trappings of power.

And yet, for all of Brown's gravitas and power, he can't simply hand the reins of the city over to Newsom. He hasn't even been able to unite the storied Brown-Burton machine behind his candidate -- his longtime friend, State Sen. John Burton, is backing Alioto, and so is his buddy Joe O'Donohue from the powerful Residential Builders' Association. Even though Brown endorsed Newsom, you get the feeling that he doesn't entirely trust him. Plus the mayor's got a mischievous streak himself and he can't help messing with young Gavin. When Gonzalez entered the race he quipped that he "made Gavin look stiffer," which was projected on a wall during the Gonzalez kickoff party in September. Brown is not known for false modesty, but the last time we talked, when I suggested he ought to be able to bring Burton and O'Donohue on board for Newsom, he told me he simply couldn't. "There's an observation of Gavin as being unreliable. So I can't go to Joe O'Donohue or John Burton and say, you can't do this. They have too many examples of unreliability."

What some call "unreliability," of course, others call independence, and there's a way that Brown's occasional public distancing may help Newsom, in a town where the mayor is a polarizing figure, loved by many but hated by more than a few. Newsom has bucked Brown, who appointed him to the board in 1997 (he's since been reelected), on several key votes, and recently said he'd replace the mayor's choice for police chief. And despite the left's depiction of Newsom as the creation of evil, monolithic business leaders, business doesn't entirely trust him either. Financier, philanthropist and liberal Republican Warren Hellman is backing Leal. Newsom is a little bit too young and -- to his credit -- too much of a synthesizer and triangulator, in the Clinton mode, for any one group to monolithically back him. His decision to support a ballot measure increasing the local minimum wage, for instance, probably cost him some business support.

I've always sort of liked Newsom, liked his wonkiness. His campaign Web site reads like a think-tank site, with policy papers on every imaginable topic; last time we talked he was pushing his plan for a local Earned Income Tax Credit for San Francisco's working poor, an underappreciated New Democrat priority, even in the face of a budget deficit. When I was profiling Matt Gonzalez for San Francisco magazine, the Green Party leader kept needling me that I was giving him a hard time -- asking tough questions about his late decision to run -- because I have a dark political secret: I'm a Bernal Heights lefty who's soft on Ammiano (he lives blocks away and represents my district). I have a dark secret, all right: It's that I like Ammiano, but before Gonzalez joined the race, I was torn between him and Newsom (I still haven't gotten over Alioto's challenging Agnos in 1991, and Leal's campaign just never added up for me). I covered Newsom's "Care not Cash" initiative last year and found myself persuaded by some of its logic: It would have slashed the cash grant the city gives the homeless from roughly $350 to $59 -- all around San Francisco, other counties have done something similar, making us a magnet for general assistance recipients -- and put the money into housing and services, creating a $14 million revenue stream for supportive housing at a time of budget cutbacks.

But mostly I hated the campaign against Care Not Cash, which was really a campaign against Newsom, in which nasty lefty know-it-alls hit him with pies, threw stink bombs into the restaurants he owned, papered the town with fliers printing his home phone number and demonized him mostly because they could. It was a thuggish kind of politics that disgusts me, and I blamed its practitioners for marginalizing someone who isn't a villain, who doesn't have horns, who had been a champion of drug treatment and a smart mind and decent vote on human service issues, whose crime it was to see the problems of poverty and social services differently from the advocacy community.

Yet lately I've had to admit Newsom deserves some of the blame, too. His new initiative, Prop. M, which bans aggressive panhandling, seems to be an exercise in divisive politics. I met with Newsom shortly before he put it on the ballot, and it was one of those days you could see the angel and the devil on his shoulders, whispering in each ear. Some liberal supporters of Care Not Cash -- most notably Human Services chief Trent Rhorer, who helped write it -- were opposing the new measure, which would ban "aggressive panhandling" -- physical contact, verbal threats, following someone who says no -- plus add new limits: no begging at bus stops, on median strips, in parking lots. It also would take the city's most Draconian laws -- technically, begging is illegal in San Francisco -- off the books, which let Newsom pitch it as another hybrid, left-right solution. But nobody was buying it. "I think Gavin truly did Care Not Cash as a way to help people," Rhorer said in April. "But I worry that there's no way you can really say this measure will do that. I mean, call a spade a spade: If you want to make the streets cleaner for businesses and tourists, do it. But don't bill it as compassion."

Newsom was irritated by the criticism from friends, but he seemed chastened by it. "We don't need a divisive campaign right now," he admitted. Then he did his sanctimonious schoolboy thing: "Look, if you want to say, 'So what if we lose another few hundred people on the street,' fine. If you want to say, 'So what if people feel insecure going to their parking lot and confronting a guy with a golf club asking for money' -- well, OK. If you want to say, 'Society's cruel and capricious.'" The next week, a judge struck down Care Not Cash on the grounds that only the Board of Supervisors can set welfare-grant levels, not voters, and suddenly Newsom was moving forward with his panhandling plans. You could watch as his board colleagues' obstinacy hardened his stance. Newsom and Brown challenged the board to follow the will of the voters and implement the homeless reform legislatively, but they refused, Gonzalez and Ammiano making common cause with conservative Tony Hall, who hated the measure because it increased spending on services.

I understood Newsom's political reasoning on Prop. M, but I didn't like it. I think the measure polarizes the city even more, and proves that Newsom's political advisors convinced him he didn't need to look to his left for votes. That's why I think it's good for the city -- and for Newsom's soul -- that he has a vital challenge to his left, even if -- maybe especially if -- he gets elected anyway in December.

But right now it's looking like he can't start measuring for new drapes in Brown's office quite yet. And the late surprise is Gonzalez's surge. Only a few weeks ago he was in fourth place, usually in single digits, in every poll I heard about, even his own. Now a Binder poll getting a lot of hype has him in second with 16 percent of the vote, way behind Newsom. But if he makes the runoff, it's a whole new race. Gonzalez would seem to be the candidate Newsom should fear most (though some in his camp deny it); no doubt his opposition-research team has a hard drive full of Alioto's vulnerabilities, and nobody, not even Ammiano supporters I'm talking to lately, thinks the lefty supervisor can beat Newsom in December. But can Gonzalez?

He thinks so. Clearly, his campaign is the most interesting game in town, relying on nightly parties and pub crawls and bringing in a wave of young, turned-off bohemian do-gooders who are otherwise cynical about politics. I like his campaign, and I mostly like Gonzalez, despite an off-putting detachment that can feel like arrogance. I liked him a lot when he debated Newsom last October over Care Not Cash. His arguments were political, not personal, and despite the viciousness of the anti-Newsom campaign he was careful to say that he liked and respected his colleague, that they'd worked well together before and would again. It took a certain amount of courage.

Now, of course, he uses Newsom as a punching bag, and there's a ruthlessness about him that seems new and maybe inevitable in someone who wants to be mayor, but off-putting in someone who claims he's about a new kind of politics. It was on view, in a small, petty way, just the other night, when Green Party guru Michael Moore was in town, and he asked Gonzalez for Newsom's phone number, so he could call him from the stage and humiliate him in front of hundreds of adoring lefties for beating up on the poor with Care Not Cash. Gonzalez hesitated, but then he phoned his pal Chris Daly and got the number, according to the Chronicle, and Moore made his prank call. There was something amusing but sort of bullying about it that just didn't feel like Gonzalez. But then I don't know him very well.

Then came Daly's PUC bombshell. Gonzalez insists he didn't know about it, and that's actually believable. But so far, he's stood by Daly, refusing to promise Brown one of the eight supervisors' votes he'll need to overturn the appointments. At first other lefties were balking, too. But then Brown did something extraordinary in his State of the City address. Declaring that the PUC "should never be politicized," he withdrew his appointments and promised to consult with the Board of Supervisors on a new list of candidates. The move prompted a thunderous standing ovation, and it was amazing to see the 69-year-old titan, who normally smites his enemies, extend a kind of olive branch. But Daly stood firm, insisting he wouldn't withdraw his appointments despite Brown's gesture.

It's become a lefty cliché that Daly borrowed a page from the wily Brown's political playbook with his PUC move, but in fact Brown's backroom maneuvers have always been more audacious, like siding with Republicans to become Assembly speaker in 1980. And in the end, the master may well best Daly this time around, too. Although Daly has been insisting Ammiano is still supporting his PUC picks, after Brown's offer to compromise, the supervisor suggested he might back the mayor, and others began to peel off too. It would have to feel good to Ammiano to decide to pay back Daly, his former ally, for defecting to Gonzalez. Now the question is: Will Gonzalez stick with Daly? And if he does, will it cost him a shot at Brown's job?

"It could decide the race," says Rich DeLeon, who calls Daly's move "outrageous and stupid" -- and remember, DeLeon counts himself on the left. "It could be like that Frank Jordan stunt, remember, when he appeared naked in the shower with those DJs?" I do remember -- in the end, Willie Brown's masterful politics didn't land the decisive blow in 1995; Jordan did himself in, by agreeing to shower with some shock jocks just before the runoff. Small things are only decisive when they crystallize a worry voters have -- in that case, it was that Jordan wasn't mayoral, even after four years as mayor. Sticking with Daly could prove to voters that Gonzalez is tough enough to be mayor; or it might prove he can't be trusted to run a city of greatness that's beloved by the left, not just by business leaders and society types.

So Tuesday's race won't decide who's mayor, but it will decide who leads the left, which is important in a city as liberal as San Francisco. Traditionally, what's described as the left is the political bloc that favors rent control and limits on downtown development, backs municipalization of public power, and opposes limits on aid to the poor and homeless. They make up no more than a quarter of the city's voters -- a 2000 survey by David Binder found that 42 percent of San Franciscans describe themselves as "liberal/progressive," 39 percent as moderate and 15 percent as "conservative" (3 percent were "other" or "decline to state.") But they serve to pull the local right to the center, and to preserve a little bit of an increasingly wealthy city's bohemian, egalitarian soul. So the race for second matters. Is a vote for Ammiano or Alioto a way of looking backwards -- both are grandparents -- while the younger, cooler Gonzalez represents a vote for the future? Will the Green Party's gumption revitalize the left, or sacrifice its links to labor (which is heavily for Alioto) and local Democrats and isolate it? Tuesday's results will answer some questions and raise more.

The only thing sure is that Willie Brown's time is gone, and it's not clear whose time has arrived. It's been several years of loss and change: Herb Caen and Giants manager Dusty Baker are gone (Brown and I found common cause in anger at watching him be driven away by the imperial Peter Magowan, unable to do anything about it); the 49ers haven't gone to the Super Bowl in almost a decade, and probably won't for a while. The dot-com chimera -- We were going to revolutionize media! And make a lot of money doing it! -- vanished, and nothing's replaced it. The tech lords who used to crawl the Mission moved away, but too many Mission families still can't afford to live there anymore, anyway. San Franciscans can shut down the city protesting the Iraq war, but can't figure out how to get the homeless off the streets. This is a fragile city, a city on a hill, on an earthquake fault, on a cliff beside a vast ocean. It deserves great political leadership, and it doesn't quite have it yet.

Shares