The female nude is ancient, one of the first things we learn about in that junior college art history course. She’s the full-figured Venus of Willendorf, the bare-breasted, nursing Madonna in religious paintings, the figure studies attributed to so many male art historical kingpins. You know the drill — nude women having an impressionist al fresco lunch with clothed guy; the nude descending staircase; the naked women covered in Yves Klein Blue and writhing on blank canvas.

Fast forward to the 1970s, when feminism and ideas about gender-specific gazes were the ideology du jour, and the female nude became a contested art genre. The political implications of unclothed women as subject became too loaded to be about pleasure or appreciation, except for boorish sorts who ignored signals of political correctness and brazenly exercised a libidinous eye.

Contemporary art is engaged in a constant reshuffling of ideas, images and the ways we receive them. These days pluralism rules, anything goes in a sea of approaches and media-generated image overload. And so we find the publication of “Curve: The Female Nude Now,” a compilation of mostly new nudes by artists who don’t so much curve around pre-existing notions as twist them into a plethora of slightly new positions.

Books filled with naked women are ubiquitous; what sets this one apart from the start is its authorship by a mostly female band of art critics (a token man rounds out the crew). They write for such tony and trendy periodicals as Artforum, Art in America, Interview, and Time Out New York. Linda Yablonsky, who contributes a provocative, tone-setting introduction, is also the author of a novel called “The Story of Junk,” a tale of a lesbian drug dealer. There’s a cachet of art world hipness, and a readily acknowledged female gaze to this useful, if not exactly titillating, collection of contemporary nakedness.

What we find is a polymorphous range of recent art that somehow acknowledges the female form, and not always literally. In the aforementioned introduction, the accompanying photograph, by Sarah Charlesworth, depicts a parted red velvet curtain with a telescope penetrating the rich folds. “This picture has less to do with what lies behind the curtain than with the powerful sense of desire it evokes, the desire to see,” writes Yablonsky. It’s a sentiment that also brings to mind that little man operating the machinery in the Wizard of Oz.

“Curve” offers a mixture of high art (painting, photography, sculpture) and fashion photography, by dozens of male and female artists, of various generations. The noticeable thread is the conceptual subtexts that are now attached to familiar images of the female nudes. Arranged alphabetically with spreads devoted to single artists whose works span the last decade, the book aims less for thematics than for laying out a multifarious range of practices, with short text illuminating aspects of each artist’s work.

Themes nevertheless emerge. Perhaps the most blue-chip trajectory are the paintings of John Currin and Lisa Yuskavage, who both create ambivalent images of voluptuously Pop women in luscious painterly styles. Currin is the subject of a current museum retrospective, and is here represented with two paintings in a style that brings to mind that old German master Lucas Cranach. They’re pictures of a curvaceous strawberry blonde wearing filmy clothes and panties that somehow manage to blur the distinctions between what they call “draperies” in art history books and low-priced contemporary fashion. The model for the pictures is famously Currin’s wife, artist Rachel Feinstein, an idea that seems to add a collaborative element — that she’s willing to submit to a kind of image with unclear motivations. And ironically, it’s that wiggly intentionality, along with Currin’s masterful painting style, that makes the images so memorable.

Yuskavage also is well-known for painting images of women she knows, only they hardly look realistic. Her nude and lingerie-clad ladies take their misty, candy-hued color schemes from old Playboy illustrations. They’re moody boudoir portraits that are a curious mixture of cheesecake, color theory and feminist critique. One of her most famous works is called Day, and features a woman, bathed in yellow light, lifting a camisole to inspect her impressive bosom and hourglass figure. The sunny overtone to the picture is akin to acidic overexposure, a sugar headache. In another work, a topless woman wearing seemingly beaded panties stands in a room awash in fleshy pink; her skin looks blanched; her expression is stern but not pained. The combination of seductiveness and curious defiance affirms a deep ambivalence and the ability to enjoy the body while somehow acknowledging its hefty ideological implications.

The same holds true for a number of photographers included here, and they manage to keep things spicy with a conceptual overlay. Katy Grannan, a recent Yale grad, makes images of naked young women that become more intriguing when you learn that she procured her models through a classified ad in a local paper offering 50 bucks to women to allow her to photograph them in their homes in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., in whatever way they chose. It just so happens that most of them asked to pose in the buff. What this trend means about contemporary womanhood is anybody’s guess, but the intriguing thing is the way their suburban homes overshadow their appealing bodies.

Curious settings also inform the photographs of Justine Kurland, whose landscapes are populated by groups of nude white women who seem like garden nymphs attending to beds of flowers or communal vegetable gardens. Malerie Marder’s color photographs show unclothed females, with ordinary bodies, in what seem like motels or generic interiors. The short entry on her work reveals that these are actually close friends and family, stripped of sartorial armor. One shows a naked middle-aged woman posing near a clothed young man. The relationships are never made explicit; again it’s the lack of resolution that packs a muffled punch. Ditto for Vanessa Beecroft’s performances in which corps of powdered, Barbie-like models stand around with disaffected expressions. The biographical tidbit that Beecroft has had an eating disorder somehow lends a bit of credibility.

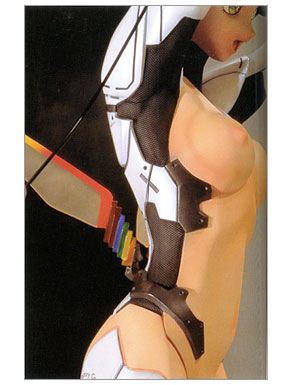

If anything, the ambiguity is the bottom line here, even when the images are by men. What are we to make of Jock Sturges’ infamous images of pubescent girls frolicking at the beach, pictures that the text reiterates were seized by the FBI under suspicion of pornography? There’s something more disturbing, not to mention unforgettable, about Japanese artist Makoto Aida, who makes fantastical manga-like prints of women as sushi — being bound up into a maki roll or having a giant male hand squeeze roe out of a woman’s vagina. Thankfully, there’s a superhero vibe to Takashi Murakami’s cartoonish paintings and sculptures, one of which features a pop goddess spewing a ring of milk from her over-inflated breasts. There are plenty of examples by artists of both genders that reference pornography (graphic and digitally filtered to a blur), the difficult nature of mediated body image, and sometimes even a genuine, pleasurable appreciation for naked ladies. “Curve” may mark multiple vista points in the winding road of undress, but thankfully, the journey doesn’t end here.