In the 1967 Six-Day War, in preemptive strikes, Israel defeated the combined military forces of three of the Arab world’s major powers — Egypt, Syria and Jordan. In the wake of the hostilities, Israel occupied land in all three countries, most notably the West Bank of the River Jordan. Many Jews believe this area to be the historic birthplace of their people. Most importantly, controlling the West Bank meant controlling East Jerusalem, the location of the ancient capital city of King David, and home to the Temple Mount and the Western Wall, Judaism’s holiest sites.

But along with the newly captured Holy Land came hundreds of thousands of Arab residents, none of whom wanted to be part of Israel. In 1968, the Jewish mayor of the newly united Jerusalem thought he had found the perfect way to make his city and his country feel more inclusive — a national beauty pageant that would feature both Arab and Jewish contestants. This is the story of one of those contestants — a winner, some would say. This is the story of my aunt, the Queen of Jerusalem, Amelie Makhoul. She requested a pseudonym for herself and her sisters in this article, but no other facts have been altered.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

The Queen of Jerusalem wears white socks, baggy blue jeans and a loose, black sweatshirt, an outfit she wears comfortably, and frequently. She sits back in the aged sofa, its once-white leather now a soiled gray. Despite her protests, her brother pours her some red wine and hands it to her in a crystal glass.

Her nephew turns down the volume on the television, momentarily. Her sisters stop their gossiping and walk into the den from the kitchen. Her brothers and cousins stop singing carols, and quietly sip their drinks, snacking on grapes and thinly sliced kiwi. Her wrinkled, half-shaven father stops complaining, a rare occasion indeed, and her mother smiles softly and chuckles under her breath.

Her family gathers around her; the queen holds court one last time.

Far from the fashion centers of Milan, Paris, London or even Tel Aviv, the Queen of Jerusalem sits on Christmas Eve in the home of her sister and brother-in-law, in Flint, Mich. The house is large and well furnished. In the backyard there’s a swimming pool with a slide. Red, blue and green lights dangle from ice-frosted trees and shrubs; snowmen sit contentedly in sprawling front yards; wreaths hang from large, forbidding front doors. You almost forget where you really are.

Several major publications, most notably Money Magazine, have over the years bestowed upon the city of Flint the title of “Worst Place to Live” in America. In his film, “Roger and Me,” director Michael Moore depicted Flint’s overwhelming poverty, interviewing a woman who had to slaughter rabbits for food. Many of the shops at the city’s strip malls closed long ago, but the liquor stores thrive, getting plenty of business from unemployed factory workers. Although the Queen of Jerusalem insists that she has never really had a home, and in fact “belongs nowhere,” Flint has served as the closest thing to home for many years. She has often driven down the blue-collar streets, lined with small, pale houses covered in aluminum siding that look almost like wood.

The truth is, the Queen of Jerusalem has not been a queen for several decades.

Today, strangers guess that she is 10 years younger than she really is, 54 years old. Over the years, though, the Queen of Jerusalem has aged — graciously, but inevitably. She has felt her once smooth skin loose its youthful resilience. She has watched her long, lustrous black hair grow dull in the cold Michigan air. Lines have appeared on her face, where there were none before.

She has married and divorced and has two children, adults now, graduated from college and on their way to successful careers. Once, years ago, the Queen of Jerusalem also attended college, where she earned a bachelor’s degree and even a master’s in microbiology. She dreamed of a big life — if not as an international model, perhaps then as a researcher or journalist. But she was pulled back here, to Flint, always near her family. For years, she managed her brother’s grocery store. She has held other jobs as well, sacrificed herself and her dreams to put her children through school.

For a long time, the Queen of Jerusalem has not allowed herself to remember what it was like to be queen. Her son has heard only veiled references to his mother’s former identity. Her daughter heard the story once when she was young, when the queen forced her little girl to take part in a Miss Michigan pageant, perhaps longing for the glory of the past. But mostly, the queen made herself forget. She refused to talk about it with anyone.

She even threw out all the old press clippings of her victory in 1968. Hebrew papers like Ha’aretz and Yediot Ahranot, and even one Arabic-language paper, all had covered the event. London’s Daily Mirror had called her success a “lovely settlement in the Middle East.” The Jerusalem Post, a Jewish English-language daily, had described her as looking “like a fairy-tale princess.” The paper featured a large picture of the queen, her brown eyes gazing seductively at each reader. The article’s headline read: “Haifa girl [is named] Israel queen; Miss Jerusalem is Arab.”

None of that matters anymore. She’s a different person now. She isn’t a queen, not really. But tonight, on Christmas Eve, years after she moved from Jerusalem to America, as she sits with her parents, brothers, sisters, nieces and nephews, she picks up her crystal glass and pours some more wine — just a little bit; she almost never drinks because it makes her sleepy. And she remembers what it was like, for a few minutes. Tonight, just tonight, she allows herself to be the Queen of Jerusalem, one last time. “The Jews told me they would take me to Paris, to London,” she says. “They told me they would make me a model. And they could have, too, if they wanted, because they control everything.”

She didn’t really want to enter the contest. She was young, only 22 in 1968. Like any good Catholic Arab girl, she lived with her parents and two younger brothers in their small, two-room home. The walls were made of stone, and the shouts of her brothers would echo off them throughout the day. Her mother served grape leaves stuffed with rice and meat, spinach pies, and baked chicken — the chickens raised in a small coop in the apartment’s courtyard, space that her family shared with its Jewish neighbors.

Unlike most Catholic Arabs, she lived in West Jerusalem, which was predominantly Jewish. Most Arabs had fled that part of the city during the war of 1948 that established Israel as a state, but her family hid in a Catholic convent on the West side until the end of the war. Unlike many other Arabs, she and her family never fully experienced the feeling of being uprooted from their homes, not allowed to return.

She, like her brothers and sisters, has a French first name. Even though her family was far from rich, the French names were the mark of educated Christians, the sign of sophistication in an international city.

In some ways, Amelie managed to successfully straddle the line between the Arab culture of her home and the fledgling Israeli culture that surrounded her. She spoke Hebrew fluently, just as well if not better than the new Jewish immigrants who kept arriving to the country. She had Jewish girlfriends. She followed all the latest Western fashion and pop culture trends. She liked to listen to Chubby Checker on the radio.

But she also felt the strain of being a minority. Growing up, when she walked to grade school, Jewish children would sometimes throw stones at Amelie and her sisters, jeering, “Aravim! Aravim!” “Arabs! Arabs!” Once she graduated high school, her opportunities for higher education were limited, because at the time Israel only allowed its Arab citizens to study agriculture or education.

Amelie’s father was an employee at the Belgian Consulate — a low-level job, but it was steady, decent work, as much as an Arab man in West Jerusalem could expect in those days. Before Amelie had even graduated from her Catholic high school, she found a job at the British Barclays Bank. She put in time in the international division, where her ability to speak French, English, Hebrew and Arabic was an asset. She did routine accounting and worked as a teller.

So why did Amelie feel the need to enter some silly beauty pageant? She was content. She had a good job. She had a good family. But she was curious. When she told her parents about it, they said they didn’t want to hear about it. They were busy with real work in the real world, just like she should be. Besides, they said, everything in Israel somehow had a way of becoming political.

But Amelie also had friends, and those friends knew that she was perfect for the beauty pageant. She was, after all, beautiful. Her black hair was long and thick, her skin smooth and dark — but not too dark — her lips full and pouting. But what people noticed more than anything else were her eyes. In the Middle East, where women of all religions have traditionally covered most of their body, and often, most of their face, the eyes are a woman’s most important feature. Amelie’s were big and brown like dark, oiled olive wood. They were so deep, so confident that they threatened to swallow you up if you looked at them too long.

It was finally a Jewish girlfriend who sent Amelie’s picture to Israel’s La’Isha — For Women — magazine, the sponsors and organizers of the Malkat Yisrael, or Queen of Israel, pageant. When Amelie received an invitation to come to Tel Aviv for the first round of the competition, she decided to go.

If Jerusalem represented Israel’s connection to the past, Tel Aviv was its future. Barely over 50 years old, the city already featured wide streets and architecture gleaned from the major metropolises of the world. Tel Aviv was like a chunk of Europe transplanted onto the sandy shores of the Mediterranean.

During the spring of 1968, Amelie began to make a series of trips to Tel Aviv for different rounds of the contest. She always traveled alone, without friends or family — her parents didn’t even know she went. Consultants hired by La’Isha helped her and the rest of the 250 contestants apply their makeup and choose what to wear. Days after the process began, hundreds of girls were sent away, leaving only Amelie and 21 others to compete for the final prizes.

The pageant would take place in Jerusalem, blocks away from the Makhoul home. The whole time, Amelie had been cool and almost detached in her approach to the contest. She still had her job at Barclays, she still lived at home with her parents and brothers.

They were supportive enough, maybe even proud sometimes, but constantly warned her not to trust anything connected to Israel. Politics, they said, trumped everything. To Amelie, though, the whole pageant was nothing, really. Just something to do. Just a beauty competition.

But as she advanced, she began to realize that matters weren’t so simple. She took more and more notice of just how far the competition could send her. If she were to win the grand prize, Queen of Israel, she would be automatically entered into the Miss Universe contest, taking place that year in Miami. Even if she didn’t win the whole thing, in the pageant’s system, she would have a chance as a runner-up of being named Miss Israel or, because she lived in Jerusalem, Queen of Jerusalem. Any of these titles would earn her modeling contracts and film deals, maybe even the opportunity to travel abroad, to England, France or Italy. In her entire life, Amelie had never even left Israel, except to occasionally visit friends and relatives in the West Bank.

Maybe this would be her chance to leave this place, where as an Arab she always felt like an outsider, where life was so restricted. Maybe she didn’t have to work at a bank. Maybe she really could be a model.

She also started to realize that her parents may have been right about Israel. Everything did have a way of somehow becoming political. Other Arabs in the community began to talk. They said she shouldn’t enter a contest run by the Jews.

Arabs had tried out for the contest in the past; they had even won prizes before. But this time, in May 1968, politics created an even greater tension. Less than a year earlier, Israel had won the Six-Day War. The victory had allowed Israel to annex East Jerusalem, the part of the city that had remained in Arab control after the war of 1948, along with the rest of the West Bank, which had been occupied by the Jordanian army for the previous 20 years. The annexation of East Jerusalem left Israel in control of thousands of Arabs. They were bitter, angry.

They had lost yet another war to Israel. They had lost even more land — Holy Land. And it had taken less than a week.

Arabs, in both East and West Jerusalem, wanted to create a united front of opposition against those they considered to be occupiers of their land. The Israeli government, on the other hand, was desperate to prove to the Arabs and to the world that Jerusalem was a united city. Yerushalayim meuchedet. Jerusalem is united.

Amelie felt shame at how easily Israel had defeated the Arabs in the Six-Day War. She was disgusted by the naiveté of the residents of East Jerusalem who seemed content to wait for Jordan to attack and defeat Israel. She knew that such talk was nonsense. That day would never come. But the defeat helped her learn something else. For the first time, Amelie and the rest of her family knew that they weren’t just Arabs. And they knew they weren’t Israeli Arabs, as Israel liked to call them.

They were Palestinians. They had their own unique nationality.

But now, more than anything else, Amelie saw the pageant as a way out of Israel. There was one more round, only one more. For now, being Palestinian could wait.

The 22 young women lined up along the stage in their evening gowns. Each wore an identical gown, silky blue with white sleeves, the colors of the Israeli flag. Before the contest, La’Isha took all the girls to fancy department stores, buying them dresses, bathing suits, makeup and jewelry, along with a gold Tissot Swiss watch for each.

Later, Amelie paraded across the stage alone, wearing a white, one-piece bathing suit, covered in gold sparkles. The spotlight that glared down blinded her, but she could feel the stares of the judges and the massive crowd that filled the auditorium at Binyanei Ha’Ouma, the largest reception hall in Jerusalem at the time.

She drifted smoothly, slowly along the runway for the casual-dress competition, and then again when all the contestants filled the stage one last time in their evening gowns. The women were judged based on their appearance only, without any interview or talent competition.

The girls left the stage to loud applause and went back to await the judges’ decision. Amelie had felt the energy of the crowd respond to her each time she walked across the stage, even though they knew she was Arab.

But she wasn’t prepared for what was to come next. The time for the judges to make the announcement about the winner passed without a word from anyone. The girls waited as the minutes ticked by. Suddenly, one of the pageant organizers burst into the room. The judges had requested that Amelie and a Jewish Israeli girl, Miriam Peri of Tel Aviv, walk before them again in a jury room, separate from the massive auditorium.

They called Amelie back again and again. She could feel them dissecting her, taking her apart as she walked slowly before them.

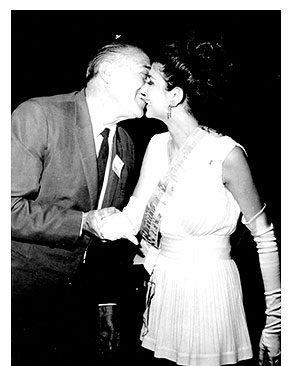

One judge in particular stood out — Jerusalem’s famous mayor, Teddy Kollek. The mayor had just become leader of a “united” city months earlier, and he had been striving to demonstrate to all of Israel’s critics that the new Jerusalem was one that would embrace both Arabs and Jews.

During the callbacks, Amelie felt the constant stare of Kollek’s small eyes peering at her from behind the judge’s table with an intensity she would never forget. He had silver-gray hair, neatly combed and parted on his left. His stocky frame and the wrinkles in his pale skin made him look older than he was, almost grandfatherly, but that just made the animosity that radiated from the slits of his eyes even more startling.

After yet another appearance in the jury room, Amelie waited again, hoping for a final verdict. A Jewish Israeli photographer approached her and whispered into her ear.

“You’re causing quite a commotion,” he said. “Most of the judges want you to be the Queen of Israel, but Kollek keeps saying, ‘Nyet.’ He wants an Arab to be Queen of Jerusalem.”

When the decision finally came down, Amelie knew who she had to blame, and in another sense, who to thank — Kollek. She was named Queen of Jerusalem, while a blond woman named Miri Zamir was made Queen of Israel, and Peri was dubbed Miss Israel, or first runner-up.

On the one hand, Amelie and the rest of her family were certain that she would have become Queen of Israel had she been Jewish; they theorized that, because the Miss Universe pageant was to be held in Miami, a city with a relatively large Jewish population, the Israeli organizers of the event didn’t want to send an Arab to represent their country in America. On the other hand, even though Amelie wouldn’t get a chance to compete in the Miss Universe competition, she still had the opportunity to win something just as valuable: an international modeling or acting contract.

Soon, she thought, she would leave this place, this home that had never felt quite like home, for the fashion capitals of Europe and America.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

“Miss Makhoul, could you please comment on what it means to you to be the nation’s first Miss United Jerusalem?” They would ask her this at every one of the events that La’Isha took her to, along with the other pageant winners. At conventions, clubs, parties, even bowling alleys all over Jerusalem, reporters and bystanders would always ask her, “How does it feel to be Miss United Jerusalem?”

Every time, Amelie would look down at the microphone, then look into the crowd. And then she would reply, “Ani lo Malkat Yerushalayim Ha-Meuchedet. Ani rak Malkat Yerushalayim.”

“I’m not Miss United Jerusalem. I’m Miss Jerusalem. Only Miss Jerusalem.”

The crowd would murmur. After the events, representatives from La’Isha, and sometimes the magazine owner’s wife, Hemda Moses, a nice but brittle old lady, would come over to Amelie and tell her, “You are Miss United Jerusalem. You have to say that you are Miss United Jerusalem.”

But she wouldn’t. And she never did.

At Amelie’s job at Barclays, she received letters from lovesick men from all over the world — South Africa, Belgium, Switzerland, England. Even Jews wrote, asking her to marry them. They didn’t even know she was Arab — they had just seen her picture, and they thought she was beautiful.

At home, though, she couldn’t make either side happy. Amelie’s sister, Susanne, had always gone to the same hair salon in East Jerusalem. After her older sister became Jerusalem’s version of royalty, though, Susanne found that going to get her hair styled had become an unpleasant experience.

“Your sister is a traitor!” they said.

“She should have never even taken part in such a competition!”

Amelie risked the anger of the Jewish community by refusing to call herself “Miss United Jerusalem.” Many Jewish Israelis were already incensed that an Arab had been declared queen of their eternal city.

Now, at the same time, she was being ostracized by the members of the Arab community — particularly those of East Jerusalem — for what they considered to be her complicity in “the occupation.” Amelie kept going to events, kept insisting that she was Miss Jerusalem only, not Miss United Jerusalem. In her mind, there was no such thing as a united Jerusalem. Just a city, a group of people, that had been annexed illegally by a foreign power, its enemy. But other Arabs didn’t care what Amelie called herself. To them, she was the queen of a divided city.

Soon the people from La’Isha began calling her less and less frequently. Until one day, only months into her year-long reign, they stopped calling her altogether.

Amelie still possessed vague dreams of being an international model. She called the magazine. She even called the home of Hemda Moses several times, asking to speak to the owner or his wife. Each time, she was turned away.

Late in 1968, Amelie finally had a chance to leave Israel. She finally had a chance to do more than work at a bank. She had a chance to travel someplace where she could fulfill all the hopes that winning the contest had inspired.

She left Israel for America. But instead of trying to model in New York, she headed to Michigan to be near her family.

She moved in temporarily with her sister and brother-in-law, who had bought a small liquor market at a cheap price after a man was shot and killed there in a robbery. Once home to some of the world’s largest and most productive auto plants, Flint had begun a steady decline by the time Amelie arrived. Increased Japanese competition and a nationwide economic recession eventually led companies like General Motors to shut down many of their factories, laying off thousands of workers and depriving Flint of its most significant source of income.

A local newspaper contacted Amelie soon after her arrival. As the still-reigning Queen of Jerusalem, she was, after all, the closest thing the city had to a real celebrity. In the interview, she still said she didn’t understand why everyone made such a big deal about her being Arab. She had never been politically inclined. To her, it was ridiculous that newspapers would picture her standing next to the blond Queen of Israel and “point out how great it is that we can even be standing side by side.”

She maintained that she left Israel for the opportunities that America had to offer. She said that the pressure she felt from both the Jewish and Arab communities in Jerusalem had nothing to do with that. She had left Jerusalem, she said, “because I didn’t think it was worth staying for. I think I’ll like it here, though.”

But Amelie didn’t stay there long, attending college, living in nearby Detroit and Ann Arbor, traveling throughout America and Europe, even spending a year in Paris. Eventually, though, family circumstances forced her to return to Flint, a city she never learned to like.

Amelie became increasingly political, even though she had never wanted to be. She watched the news every evening. She looked on as Egypt signed a peace treaty in 1979 with Israel, leaving the plight of the Palestinians unresolved. She watched as Yasser Arafat’s PLO was expelled from Jordan, then Lebanon, never succeeding in liberating the West Bank or Gaza from Israeli occupation. She watched as Palestinians finally took it upon themselves to rise up against Israel. During the first Palestinian intifada, from the late 1980s to the early 1990s, whenever the news featured the conflict, she would silence her family as she turned up the television volume and pressed “record” on the giant VCR. Even after the intifada ended and the Oslo Accords were signed in 1993, Amelie still never trusted Israel, believing that “the Zionists” did not understand honor or principle, but only politics.

“The Jews control the world,” became something she said often.

In 1999, an Arab-Israeli woman, Rana Raslan, was named Miss Israel for the first time in the nation’s history. Raslan was 22 years old, the same age as Amelie when she came so close to being crowned Israel’s Queen. Amelie was furious. Just as when she was made “Miss United Jerusalem,” everyone claimed that Raslan’s victory had nothing to do with politics.

Amelie sat down and typed out an angry letter to the New York Times, where she had first read about the Arab Miss Israel.

“You are just perpetuating that Israel is a democracy, when really it’s not,” she wrote. “That’s a lie.”

She wrote five letters in all. Not one of them was published.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

In her brother-in-law’s house on Christmas Eve, the Queen of Jerusalem sits back in her leather seat and rests. She has just finished telling a story that many of her family members never thought she would share again, and that others had never even heard.

The TV drones on as her nephews and her son and daughter flip the channels from one old Christmas movie to another. Her sisters chatter away in the kitchen, munching on cashews and dates as they prepare a tray of sweets — baklava, apple pie and cheesecake. Her brothers, cousins and husband continue to sing carols in the living room around a tree that is glowing with white Christmas lights. Some relatives start to leave for their homes, parting with phrases like “Merry Christmas” intermingled with “Kul senna wa’intay selmay” — “Every year, may you have health and peace.”

It’s over now. Done with. Her life has been relatively successful, after all.

She escaped Israel, and because of her sacrifices her children will have opportunities she never did. She even finally escaped Flint — for good this time — moving to a house on a lake nearby, so she could be close to her family.

Still, every now and then, even though she never talks about it, even though hearing other people talk about it makes her furious, she wonders what it would have been like. She wonders what it would have been like to model in Paris, or to star in a movie in London. She wonders what her life could have been if she had lived in New York instead of Flint.

Having finished her second glass of wine, she props up her feet on the coffee table. The lines on her forehead, at the corners of her mouth, fade as she closes her eyes. Amelie Makhoul, the former Queen of Jerusalem, drifts off to sleep and dreams of all the different places she could be now.