What do actors do, really? Those of us who go to the movies with any regularity recognize, subconsciously or otherwise, that there are all sorts of ways for actors to engage us. Sometimes we want them to be a set of molecules that dissolve before our very eyes, leaving nothing but an imprint of pure character on the screen. Other times we’re perfectly happy to acknowledge that what we’re watching up there is, say, Julia Roberts filling in for a character — which is not to say she’s not acting, but that her Julia Roberts-ness is so inextinguishable that it can’t be divorced from her craft.

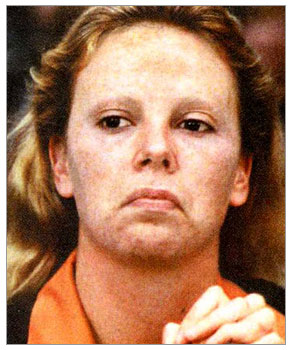

In “Monster,” Patty Jenkins’ sharply made and shattering debut, Charlize Theron — carrying an extra 25 pounds and wearing dental prosthetics — plays a fictionalized version of real-life serial killer Aileen Wuornos, who was convicted of six murders in 1992 and was executed in Florida in 2002. Part of the impact of Theron’s performance may lie in the fact that, for the movie’s first half hour or so, we’re working hard to find Theron inside the character of Aileen.

We’ve all heard about the weight gain and the prosthetics, and yet it’s still hard to believe that this Aileen — an imposing woman whose meaty, confident stride is a pronounced counterpoint to the disgruntled desperation on her face — has any link whatsoever to the willowy Theron we know. Whether we’ve walked into the theater believing that the extra weight and the prosthetics are no more than trickery, or that they’re symbols of dedication that must surely result in a great performance, we all know that the dazzling blond movie star is in there somewhere.

But where is she?

Eventually, we do find Theron inside Aileen, in a small flicker of the eyelids or in the way she laughs after tossing off, coltishly, a nervous little joke. But the real wonder of the performance isn’t that we forget it’s Charlize Theron we’re watching; it’s our realization that she has put herself completely in the service of her character — given herself over to be used, subsumed. This is different from Nicole Kidman’s strapping on a putty proboscis to portray the great authoress Virginia Nose. Theron has mastered the carriage and the speech patterns to play Aileen Wuornos (or more specifically, the fictionalized Wuornos of this movie), and with the prosthetics, she has the right all-around look. But it takes more than actorly craft to be able to pour yourself, as she does, into the body and mind of a person none of us would want to be. It’s as if she’s liquefied her own soul.

While we all know that great performances can happen in mediocre, or even bad, movies, it probably doesn’t hurt Theron, or her costar, Christina Ricci (who gives her best performance in years), that there’s a markedly intelligent sensibility behind “Monster.” Jenkins, who also wrote the script, doesn’t attempt to turn Wuornos into a misunderstood feminist hero, or even to portray her as a victim wronged by the system. The real-life Wuornos had been sexually abused as a child and became a prostitute at age 13. As an adult, she was a drifter who made a living for herself as a highway hooker, and she claimed that some or all of the seven murders she confessed to (she was eventually convicted of six of those) had been committed in self-defense.

But Jenkins is less interested in Wuornos’ innocence or guilt than she is in probing the humanity of a person capable of committing such nakedly inhumane acts. She shows us the first murder as a clear act of self-defense: Aileen has been picked up by a john. He knocks her out and, after she’s come to, proceeds to brutalize her. (“Do you want to live till you die?” he hisses at her at he goes about his business.) Jenkins handles the rape with incredible skillfulness, minimizing the sensationalism of it while preserving its horror. Although it’s not particularly graphic, it’s difficult and affecting to watch: After the rape and the murder it incites, the sight of Theron’s Aileen, stumbling and bloodied, still coming down from the peak of her rage, has all the intensity of Greek tragedy.

The first murder is simultaneously brutal and sensible, a necessary act and a cathartic one, and Jenkins lures us into thinking that “Monster” might be a vigilante movie, one in which Wuornos stands in for all women who have been wronged. But the subsequent murders are very different in tone, both from the first one and from one another. Each has a specific mood and character, and Jenkins stages them so you feel the weight of the dying men’s suffering — it doesn’t matter that some of them have treated Aileen badly and others (like the one played by the astonishing Scott Wilson, who begs for his life) have been extraordinarily kind to her. In the end, there’s a sameness to human suffering that defies our perceived right to decide whether or not it’s deserved.

Jenkins, wisely, never turns Wuornos into a symbol of anything. And in that respect, “Monster” is resolutely feminist: It acknowledges Wuornos’ victimization without simplistically treating it as the root of her psychopathology. In Jenkins’ view, deranged or not — and the evidence suggests that she was — Wuornos is responsible for her own actions. At the end of the movie, when Aileen is convicted, she rails at the judge, asking him how he could do this to a “raped woman.” But the scene isn’t played to make us feel that Wuornos’ acts were justified in any way. Rather, it’s a desperately sad giveaway as to how she defines herself when the chips are down — that is, when she’s not wielding the false power of a gun.

“Monster” is a compassionate picture without any obvious agenda. And it’s effective precisely because it’s not a polemic. This isn’t an overtly anti-death-penalty statement, although the central question it asks — how do we respond to any human being who’s lonely or in pain? — leads us straight into the questionable morality of capital punishment. Instead, Jenkins recasts Wuornos’ story as a haunting romantic tragedy, and the device works, because we all know how susceptible we are to love: Doesn’t it follow that love can expose the vulnerabilities of even a serial killer?

The hub of “Monster” is the love story between Aileen and the young woman she’s fallen for, Selby (Christina Ricci), who has fled her excessively religious family in Ohio to find a bit of adventure, or something like it, in Florida. The two hook up one evening in a Daytona Beach gay bar. Aileen has wandered in, either not knowing or pretending not to know what kind of a place it is. Selby, as perky and open as a baby bird, sidles up to her, hoping to talk to her, and you wonder why: Aileen’s face is a pale, freckled mask with all emotions save defensiveness clamped out of it.

When Aileen speaks, the words tumble out of a mouth that’s permanently turned down at the corners, making every syllable sound profane and belligerent. You get the sense it’s her true nature to be gregarious and regular (she calls everyone, male and female alike, “man”), but her innate friendliness has been calcified by caution. Her eyes, deep brown and framed by invisible blond eyebrows, are unnervingly pupilless. They can’t be read.

Somehow, though, Selby coaxes Aileen into coming home and sharing a bed with her, platonically. Selby is staying with some friends of her family’s; they’ve given her a small room. Selby, most likely intuiting that Aileen is homeless (Ricci is so subtle that she knows better than to let us hear the “click”), suggests that she might like to take a shower. She lends her some pajamas with playing cards on them. Aileen emerges cautiously from the bathroom, her long, weighty limbs sticking out awkwardly through the sleeves and legs of the cozy flannel, as if she were a kid dressed up in an alien’s costume at Halloween.

And from there, the love story in “Monster” proceeds, at first tentatively and then with rushing tenderness — the inevitable tragedy will come later, but the strange and beautiful bubble that encases the lovers in the movie’s first hour is what makes its characters so devastatingly real to us. As Selby and Aileen lie in bed, stiffly, like side-by-side soldiers, Selby makes a gentle, sincere overture: “I can’t believe you’re here,” and then, “You’re so pretty.” The words seem meant for a different woman from the one who’s actually in the bed: We can’t yet see any beauty in Aileen, who’s closed up tight like a fist. But the moment is like a dormant paper flower that doesn’t open until a few scenes later — we see that Selby was a step or two ahead of us, and as Aileen comes around to the idea that for the first time in her life she might actually be loved, she begins to look like something approaching beautiful.

Ricci is a sometimes marvelous actress who, most recently, has too often coasted on being voluptuously cute. But she doesn’t coast here. As Ricci plays her, Selby is a delicate calibration of generosity and selfishness; the flip side of her childlike neediness is a potential for treachery. Ricci and Theron look so comfortable in their love scenes that the affair between Aileen and Selby, unlikely as it seems on the surface, makes perfect sense.

Jenkins stresses its fragility as much as its passion. When the two make love for the first time, holed up in a dingy motel room, Jenkins sets the scene to Tommy James and the Shondells’ “Crimson and Clover,” the wistfulness of the song curling around the lovers like a leafy canopy. Even when Jenkins cuts the scene — we next see Aileen and Selby moving out of the crummy little motel room and into a crummy little rented house — she doesn’t cut the music. The song, which begins in a honeymoon hideaway and ends in a cottage built, miserably, for two, follows them like an echo, its last strains the tail end of their happiness.

By that point, we’ve already had a glimpse of Aileen’s fierceness, and her ability to pull the trigger even on men who haven’t abused her is that much more frightening in light of the desperate tenderness she shows with Selby. Theron gives us a character we can neither approve of nor turn away from: We have to hang on to both her vulnerability and her cruelty simultaneously. There’s no simplifying her.

You won’t be alone if you find yourself ruthlessly scrutinizing Theron’s performance at first. The prosthetics and the weight gain render her almost unrecognizable — who wouldn’t wonder if they’re just part of a stunt? In the movie’s first half hour, it’s impossible not to fixate on Theron’s crooked, too-yellow teeth, the puffiness of her jaw line, the way the extra weight has settled around her neck, upper arms, midriff and thighs as comfortably as if it’s always been there. But Theron inhabits Aileen’s skin so convincingly that I’m certain she could have done it even without the weight gain, precisely because it took me so little time to look past the extra pounds — to look right past anything resembling actorly technique, for that matter. Theron renders technique invisible, which is the whole point. Her expressiveness is heartbreaking: Aileen is a recessive, self-protective character, but Theron lets us look right inside, as if we’re privy to a secret. It’s one of the most intimate performances I’ve ever seen on-screen.

I hate to talk about “Monster” as Theron’s breakthrough movie, the one in which she proves she’s “really” an actress. Theron has already shown a confident, intelligent spark in pictures like “The Cider House Rules” and “The Italian Job.” But as with plenty of other actresses in Hollywood, her beauty has been something of a liability. Face it: A starlet isn’t an actress until she’s proved otherwise. (Which is part of the reason, I’m sure, that Kidman was compelled to wear the phony nose, despite the fact that she’d already proved herself without it in pictures like “Eyes Wide Shut” and “Moulin Rouge.”)

The physicality of Theron’s performance reminded me of Laurence Olivier’s in “Othello”: He moved like a man three times his size, his gait rolling and lumbering and overtly sexual. Theron holds Aileen’s suffering clenched in her frame. She moves like a man; her swagger is motored by false bonhomie. (Not that Aileen and Selby play out any stereotypical butch-femme roles. Aileen isn’t so much a “male” lover to Selby as she is a father figure — as if she were striving to be the father she herself never had.)

Theron’s performance has so many fine gradations, particularly as Aileen’s wariness of Selby falls away. The muscles around her mouth relax and soften just a bit; her eyes seem warmer, although they remain depthless — you can never see to the bottom of them. Both Theron’s performance and the movie’s aura of doomed romance (they’re inseparably entwined) haunted me for days. And one early scene in particular, in which Aileen and Selby meet up at a roller-skating rink, has stuck with me for weeks.

Up to this point, Selby has taken the lead, hoping to draw Aileen out. It hasn’t worked too well: We can see how withdrawn and guarded Aileen is, even though we know she likes Selby very much. Aileen may have zero confidence, but she does know how to skate. She coaxes Selby, who doesn’t, out onto the floor, and the two whirl around to Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’,” Aileen bobbing and gliding along, urging the much clumsier Selby to “feel the music.”

Aileen doesn’t fit into the world, and yet she’s at home, and temporarily very, very happy, in a roller-skating rink, where she can fly on wheels instead of lugging the weight of her lifetime on her back. In the context of what happens to Aileen later, the scene is almost unbearably painful. But for those few moments, she fits right in, gliding along to a song she loves, and just for that space of time, taking the words to heart.