In many ways, 2003 was a depressing year for music. The New York rock explosion of 2001, from which we'll be feeling the aftershocks for years, enshrined as the cutting edge of cool a shameless and sadly unironic parroting of the past. That ethos spread far from Brooklyn this year, and it was disheartening to see just how much acclaimed music demonstrated an enormous debt to the past, and very little to any kind of personal vision. This was a year in which it was easy to feel that there was nothing new under the sun. At least, it was easy to feel that way if you didn't listen to any hip-hop.

Full disclosure: I know very little about hip-hop and have only recently started buying the albums rather than just listening to singles on the radio. And yet, it was hip-hop that gave me hope this year, that made me feel that perhaps this really was an exciting time in music. I was not alone in that feeling. The Grammy nominees were announced last month, and they are overwhelmingly hip-hop dominated. During the week of Oct. 4, the top 10 singles on the Billboard chart were, for the first time, all by black artists. We've been told for years now that hip-hop has arrived, that it is now the dominant genre in the music business, in much the same way that every day for the last three months an article has appeared somewhere with the news that Howard Dean is on his way to becoming the front-runner in the race for the Democratic nomination. Hopefully the Billboard stat and the Grammy nominations list will act as Al Gore's endorsement did, and put to rest some of the novelty.

Exhibit A in the hip-hop revolution this year was OutKast's double album, "Speakerboxxx/The Love Below," really a pair of solo albums by Big Boi and Andre 3000, the group's two members. Andre 3000's glittering mindfuck of a record, "The Love Below," qualifies as hip-hop only because it is so clearly a product of hip-hop culture. Musically it's all over the map, refusing to be tied down, held together only by Andre's brilliance at turning a zany idea into a successful song. The eclecticism and the humor become a little wearying after a while, though, and unless you have an unusually high tolerance for musical theater with dirty lyrics, you may find it difficult to get through the entire record, and prefer to focus on brilliant singles like "Hey Ya!" or, even better, "Spread."

Unlike Andre, Big Boi is content to reinvent the music from the inside, and this attitude results in a far more listenable and, in the end, important album. "Speakerboxxx" plays with complete assurance from beginning to end (quite a feat for an album that's nearly an hour and 20 minutes long), gently nudging hip-hop forward as it goes. That an album this experimental and this groundbreaking made it to the top of the charts is extraordinary. The only other chart-topping record in recent history that can even begin to compete is Radiohead's "Kid A." But where "Kid A's" popularity felt like a non sequitur, a delightful but ultimately meaningless joke, OutKast is part of something bigger.

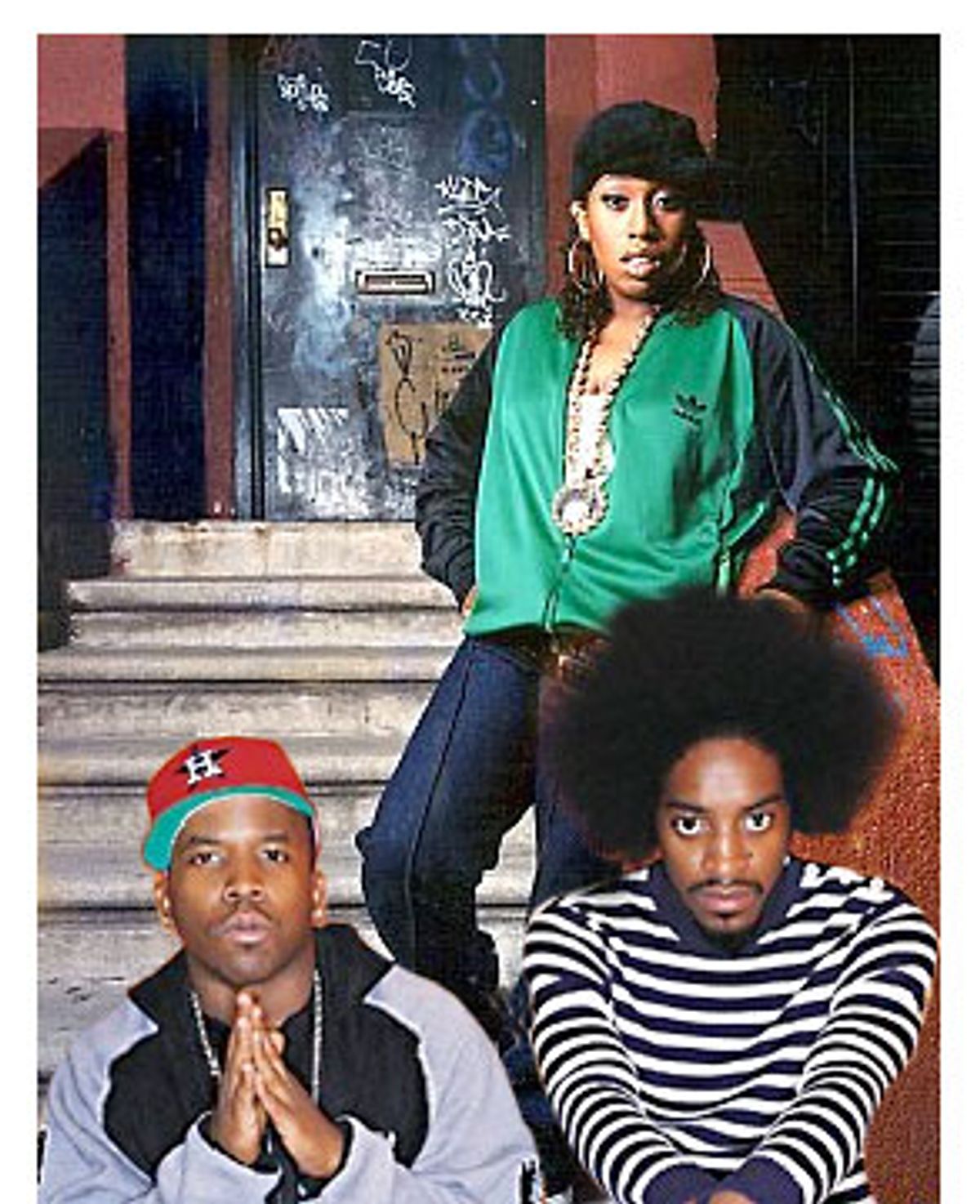

That something is a spirit of experimentation and true artistic exploration injected into the highest echelons of commercially successful hip-hop. Leading the charge is the producer Timbaland, best known for his work with Missy Elliott. Following close behind him are the Neptunes, aka Pharrell Williams and Chad Hugo. These three men are responsible for an astonishing number of hit songs, and while the Neptunes are certainly capable of slipping into mindless commercialism, by and large their productions are adventurous and sometimes even groundbreaking. The closest you can come to guaranteeing a hit song at this point is to work with one of these producers, almost regardless of who the artist is. They are pushing the music industry back toward the way it worked before the late '60s, when the producer was more important than the performer: It mattered less that a record was by the Ronettes or Dionne Warwick than that it was produced by Phil Spector or Burt Bacharach.

These producers are particularly impressive in the way they bridge the gap between hip-hop and pop, producing hits by artists like Christina Aguilera, Justin Timberlake and Britney Spears. Rolling Stone recently named Timberlake the new king of pop and artist of the year, a ludicrous assertion given his weak, pretty-boy Michael Jackson imitation. His album is listenable, and a hit, because of the production provided by the Neptunes and Timbaland. What cannot be overemphasized is the strangeness of the music they make, particularly Timbaland. His beats are often marked by their spareness and minimalism, but they rarely fail to astonish, combining a few sounds in a totally unexpected way. His new single with the Southern rapper Cee-lo, "I'll Be Around," is, for me, the most exciting song of the year. Missy Elliott's just-released "This Is Not a Test" might be her best album yet, and it's certainly one of my favorites of the year. As usual, it is largely produced by Timbaland, and he provides a stunning array of beats, all of which involve heavy bass sounds and stuttering, slightly disorienting rhythmic alignment. Despite the basic similarity of the beats, they never feel repetitive or stale. It's like James Brown in the glory days, when he and Bootsy Collins turned out bass line after bass line that followed many of the same rules, but never failed to be exciting.

This is not to say that the only exciting hip-hop or pop this year was produced by Timbaland or the Neptunes (see 50 Cent's "In da Club," produced by the sometimes brilliant Dr. Dre) or, indeed, to suggest that the only noteworthy music being made this year was hip-hop.

Coldplay somehow overcame the criticism that they were just a weak version of mid-'90s Radiohead to become an absurdly popular and critically respected band. All this despite still sounding like a weak version of mid-'90s Radiohead. Chris Martin's melodic gifts are formidable, and he's an amazing singer. But the band as a whole tends toward a kind of cheap, bombastic sentimentality, U2 without the very real grandeur. And the lyrics? "God gave you style, God gave you grace/ God put a smile upon your face." Ouch.

As for Radiohead themselves? They put out "Hail to the Thief," in many ways the album everyone was hoping they would make. That is, a happy blend between the catchy prog-rock of "OK Computer" and the fractured experimentation of "Kid A." Perhaps living up to expectations is the worst thing a band like Radiohead can do, though, because I think this was the year that Radiohead lost their elusive status as "most important band in the world," a title they had owned for at least the last four years. While "Hail to the Thief" is no less brilliant than their last few efforts, it is permeated with an unpleasant coldness, a heartlessness that makes it a difficult album to love.

This was a banner year for the recently invented "Americana" genre, a largely bogus grouping of singer-songwriters with varying degrees of twang. Emmylou Harris released "Stumble Into Grace," another gorgeous album showcasing her peerless singing, and produced by Malcolm Burn with slightly less ham-handed tactlessness than usual. Lyle Lovett's "My Baby Don't Tolerate," while not quite as spectacular as his 1996 Grammy winner "The Road to Ensenada," and featuring a bit too much of the cutesy goofiness he can lapse into, served as a reminder that he is the kindest, most compassionate voice in pop. Lucinda Williams' "World Without Tears," perhaps her best record yet, has her voice in top form, spitting and drawling through songs with that inimitable combination of macho toughness and vulnerability. My vote for most heartbreaking moment of the year is when her cracked voice sings "Baby sweet baby if it's all the same/ take the glory any day over the fame" on "Fruits of My Labor."

Americana also lost its former poster boy this year, everyone's favorite brat and Parker Posey's current beau, Ryan Adams. After toiling on a record titled "Love Is Hell" for far too long, he finally turned it in to his label, Lost Highway, which rejected it. So, in two weeks, he wrote and recorded "Rock N Roll," a loud, sloppy, distortion-heavy record that gleefully rips off a host of '70s and '80s rock bands, from the Smiths to the Stooges.

What separates Adams' parroting from that of his more solemn peers in Brooklyn is the forthrightness with which he does it. At a recent concert in New York, he prefaced the song "So Alive," which sounds shockingly like U2 if the Edge's delay pedal had broken, by saying, "I'm donating the proceeds from this concert to charity. See, I'm being like Bono." The other thing that separates him is his savantlike talent and versatility as a songwriter. He is his generation's Paul McCartney, only with a little less innate cheesiness, capable of churning out reams of brilliant songs in practically any style. The shelved "Love Is Hell," now released as two EPs, showcases these skills like never before. It is Adams' most complex, least purely derivative work to date, and Lost Highway would have done well to release it as a full record and to give it the kind of marketing put behind "Rock N Roll."

"Love Is Hell" also makes clear the enormous influence that Jeff Buckley has had on Adams' work. Both Buckley and Nick Drake, two prodigiously talented musicians who died far too young (three decades apart), are exerting an ever increasing influence on music being made today. Drake can be heard nearly everywhere that quiet, intimate music is being made, but particularly in the work of young singer-songwriters like Josh Ritter and Damien Rice. Unfortunately, while both Ritter and Rice are talented, Ritter is a little too dull, and Rice a little too melodramatic, for their music to have nearly the impact of the phantom Drake.

Buckley's influence has been perhaps a more useful one, pushing singers into a new, operatic frontier, with a surplus of vocal plasticity. You can hear him not only in Ryan Adams but in Coldplay's Chris Martin and a host of other, lower-profile singers. The best of them are able to take the inspiration of Buckley without indulging in the compulsive gilding-the-lily excess that Buckley himself was unable to resist.

This was also a good year for the carefree joys of power pop, led by those bards of New Jersey, Fountains of Wayne. Their "Welcome Interstate Managers" garnered extravagant praise and even earned them a surprise Grammy nomination for Best New Artist (the surprise stemming partly from the fact that they've been releasing music for the last seven years). These guys have some serious songwriting skills and a pretty great sense of humor ("I saw you talking/ to Christopher Walken"), but in the end the record comes off as a kind of tour de force of flippancy, always opting for the clever turn of phrase.

More enjoyable was "Electric Version" by Canadian pop-collective the New Pornographers, who cram a ridiculous number of hooks into every song, with a nice oddball edge that recalls the best of Brian Wilson. But my favorite power-poppy release of the year was "Yours, Mine & Ours," by the Pernice Brothers of Northampton, Mass. Their songs are straightforward enough, but they'll work their way into your head with great persistency, and Joe Pernice's delicate voice is a source of great melancholy and nostalgia.

And the world of indie rock? The genre name, which once meant something quite specific, has bulged and bloomed in so many directions that it's impossible to pin down accurately. Still, there were some obviously important events. Washington, D.C.'s Dismemberment Plan broke up, depriving the world of the tightest live band in existence. Fans and critics got a bit sick of Bright Eyes' Conor Oberst (maybe that's just wishful thinking on my part) and embraced Ted Leo as indie rock's new hero. Leo's "Heart of Oak," recorded with his band the Pharmacists, is certainly one of the year's most exciting records, the perfect punk rock music for ectomorphs. An album of unexpected brilliance came from Chicago's Califone, with Tim Rutili's quizzical lyrics and dry voice set amid a thicket of old American folk music and electronics.

Then there was Yo La Tengo, the most consistently satisfying band of the last few years (especially extraordinary given how amateurish they were when they started out), with "Summer Sun," a slightly subpar but still extremely satisfying album, featuring the band flexing its formidable pop songwriting skills. Better still was "Trust" from Low, one of Yo La Tengo's few peers. The sonically stunning record, produced by Tchad Blake, adds a touch more rock 'n' roll energy to Low's slow burning, deeply moving sound. Best of all was lady Cat Power, aka Chan Marshall, with "You Are Free," her third unreasonably good record in a row. Her voice is haunted. Her music embodies a certain kind of modern alienation that borders on autism, but there's no whining angst here, no mindless self-indulgence. She's making great and thoughtful art, and her vocal discipline is extraordinary.

The mood of autistic alienation in Cat Power's music can also be found in the work of Chris Whitley, one of the great, and sadly overlooked, musical talents of our time. From his adopted home in Germany, he put out "Hotel Vast Horizon," a strange, elliptical album that doesn't quite rank with his best work, but was still one of the best releases of the year. If there's any justice, 100 years from now he'll be considered one of the major musical voices of the 20th century.

Continuing with the theme of justice, I sincerely hope that the buzz around the White Stripes, which has built steadily over the last four years, will wither and die with the new year. Jack White is extravagantly talented, but he's also extravagantly obnoxious, and his arrogance is every bit as stunning as his guitar playing. Good as "Seven Nation Army" is, the universal adoration accorded to "Elephant" is surely some kind of cosmic mistake, waiting to be righted.

Norah Jones, clutching her five Grammys, was another phenomenon that was impossible to ignore. A friend of mine calls her "the Pottery Barn of the music world." The description is spot-on, capturing the mundanity, the overwhelming tastefulness, of her music. But I happen to have a soft spot for the Pottery Barn (it's a great place to buy floor lamps), and while I find Jones' record a bit boring, her music is by no means as objectionable as the syrupy sludge poured out by Diana Krall (whose recent marriage to Elvis Costello, incidentally, surely marks an irrevocable fall from grace for that former titan of popular song). Jones' mixture of folk and nonconfrontational jazz was done earlier, and better, by Cassandra Wilson, but she has a lovely voice and obvious charm.

There's no doubt much I've forgotten in this brief review of the year in popular music. There's also much I've left out on purpose, some good (Christina Aguilera's "Beautiful," the merciful withdrawal of rap-rock, Erykah Badu's brilliant "Worldwide Underground," which reinvigorated neo-soul), and some bad (the horrid proliferation of bands formed of 20-something white boys playing loud rock filled with angst and bile). I plead indifference to Alicia Keys.

There were also some tragic deaths in the music world, including those of Joe Strummer, Celia Cruz and Warren Zevon. We lost Nina Simone, the shape-shifting high priestess of American song. In her final concerts, she'd lost much of her voice but none of her famous feistiness, bellowing obscenities at her audience. And, of course, the first couple of country music, June Carter Cash and Johnny Cash. The simplicity of Johnny Cash's music, his artistic single-mindedness, remains an inspiration. Very few musicians lived and worked through so many generations. Even fewer touched all of them to the extent that he did.

Maybe Johnny Cash was depressed by what he saw, by the pretentious posturing of the Williamsburg hipsters and their retro bands, by the increasingly crass decisions made by major record companies in their endless search for fresh young meat. But perhaps, if he turned on the radio and heard Missy Elliott's "Pass That Dutch," he would see what I see: that for the first time in my lifetime, and maybe the first time since the Beatles, the most exciting, innovative and important popular music being made is also settled happily at the top of the charts.

Shares