Toward the end of "The Fog of War," Errol Morris' deeply important and haunting documentary about the hard-won lessons of history, the subject of the film, former Defense Secretary Robert Strange McNamara -- shrunken and liver-spotted, but older and wiser now -- quotes from T.S. Eliot's "Four Quartets":

"We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time."

In "The Fog of War," Morris, who throughout his career has raised documentary filmmaking to the level of art, succeeds in showing us well-worn pages from our past -- the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, the Vietnam War -- in such a way that we know them for the first time. Though McNamara has not fully come to terms with his past as the numbers-driven architect of the Vietnam War, his impassioned grappling with that war and the rest of his defense record make for a uniquely fascinating history lesson. Morris began his interviews with McNamara before 9/11 and the war in Iraq. But the film, with its insights into how even the most rational officials can blunder and deceive themselves and the public into epic tragedies, has struck a chord that Morris could not have predicted.

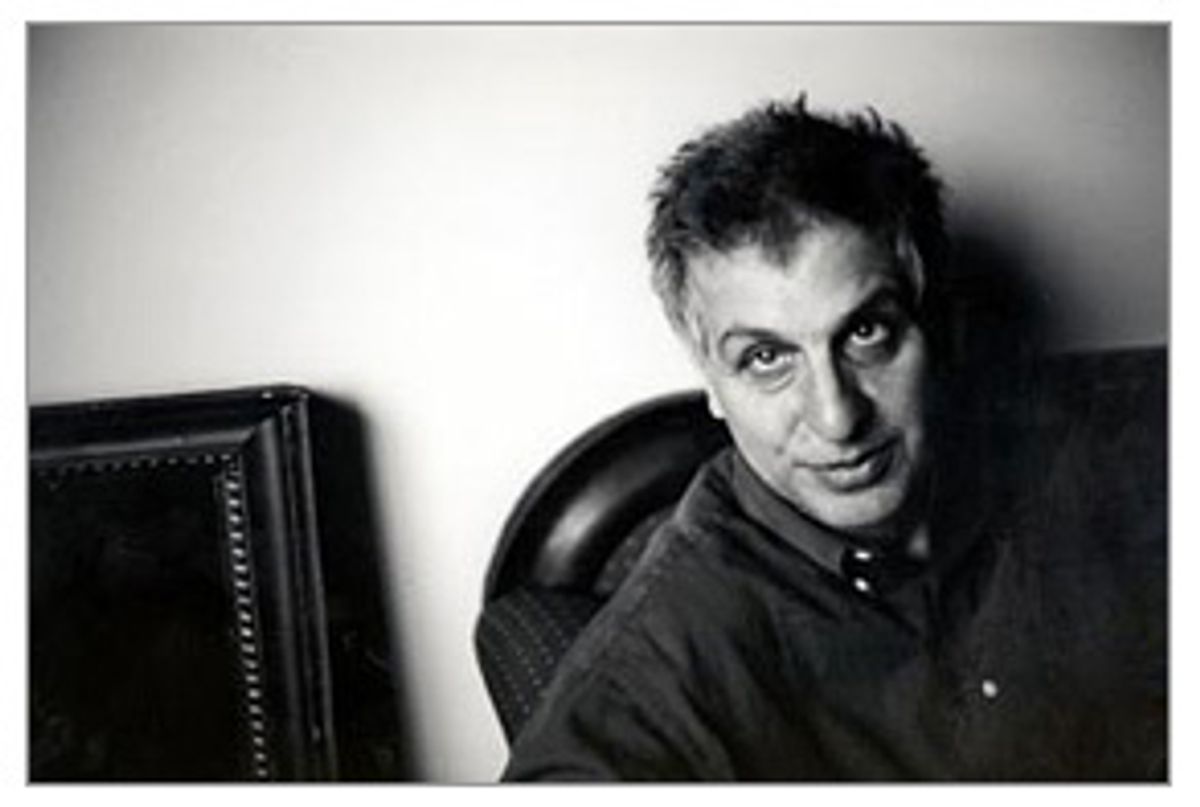

Salon spoke to Morris (before "The Fog of War" won the Oscar on Sunday for best documentary) by phone in Cambridge, Mass., where he works and lives with his wife, art historian Julia Sheehan, and their son Hamilton.

You are responsible, in a way, for rehabilitating Robert McNamara. And yet he still remains a troubling figure for many people, who criticize him for not speaking out during the Vietnam War about his growing doubts about the war -- even after he left office in 1968. You must have a pretty good sense of the man by now. What prevented him from speaking out?

It's a question that I certainly would like to answer, but I'm not sure I can answer. If it was a mystery when I started making this movie, it remains a mystery having finished the movie. McNamara was up in my office yesterday for a number of hours, and the issue comes up again and again and again and again: Why didn't you speak out back then against the war in Vietnam? You talk to different people, they have different complaints about McNamara, different reasons why they hate him.

I know when I spoke to [Vietnam War correspondent] Frances Fitzgerald while I was making this movie, she said it was the fact that she would get off these transports from Vietnam at Andrews Air Force Base, where there would be crowds of reporters, and McNamara would say over and over again, "Things are improving. We're winning the war" -- when he knew otherwise. Basically, he lied to the American people, and possibly to himself. For other writers, like my friend Ron Rosenbaum, it's the fact that he didn't speak out after he left office in 1968. The fact that he continued to serve Johnson despite his doubts about the war, that's maybe OK, but it's not beyond the pale. What for him is beyond the pale is that he left in early '68, and we all know that the war went on and on and on and on -- '69, '70, '71, '72, '73. And he still did not speak out. Fifty-eight thousand American dead, millions of Vietnamese, and there he was, safely ensconced as president of the World Bank. For him, that is inexcusable.

What do you feel?

You know, it depends on which day you ask me. Someone asked me this earlier today -- that I should talk more about my father. My father died when I was 2 years old. I have no memories of my father. McNamara is perhaps the ultimate father figure. He was the father figure in some way for a generation. Maybe that's making too much of it. But for me, having this relationship with him -- and it is a relationship, it would be incorrect to claim otherwise -- produces such a range of emotion for me. It's not as if, say, close to 40 years later, I've come to love the Vietnam War, a war which I demonstrated against in the late '60s and early '70s. I found the war appalling then, I find the war appalling now, I've had no reason to change that view. That has been a constant.

It's not only people on the left who are deeply disturbed by McNamara, of course. He's also vilified by the right, who believe that he forced the military to fight with one hand tied behind its back, out of fear of widening the war.

Absolutely. As I point out often, McNamara got the hat trick. He's hated by the left, the right and the center. Congratulations!

"The Fog of War" focuses of course on McNamara's career, but I think it's touched a public chord because the lessons of Vietnam resonate in Bush's America. Was that your intention?

I started my interviews with McNamara well before 9/11, but as we worked on the film, I would show various sections of the movie, and eventually rough cuts of the movie, to different people, and they would constantly point out, "This is incredibly relevant ... The movie should be out today."

I don't believe that history exactly repeats itself. That's not the argument. History's like the weather -- it never exactly repeats itself. And there's a danger in making inappropriate and false analogies, but it's really hard to look at this story without seeing parallels, common themes. I think about why I was attracted to doing this movie with McNamara in the first place. One of the reasons most certainly is that his stories, whether he knows it clearly or not, his stories are about error, confusion, mistakes, self-deception, wishful thinking, false ideology. It's a cornucopia of bad stuff, of human failings. And what's so interesting is that in some form or another, we see them in play today.

You see in the film the story behind the imagined attack by the North Vietnamese on two U.S. destroyers in the Gulf of Tonkin on Aug. 4, 1964. Never happened. We imagined it. We imagined something that wasn't there. Sound familiar?

Another riveting section of your film deals with the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962, when McNamara says we were a hair's breadth away from nuclear holocaust. It's startling for people today to realize how close we were, and how hard-pressed Kennedy and his inner circle, including McNamara, were by the military hard-liners to go to war.

There's an amazing moment if you listen to the recordings when the Joint Chiefs confront Kennedy. And it's really, really, really frightening.

What do they say?

They're basically saying that Kennedy should invade and bomb Cuba. And he should do it sooner rather than later. All he's doing through delay is giving the Soviets more time to get ready to launch an attack on the United States. That delay is unconscionable, and that anything other than a military response is unconscionable. There's a moment -- you listen to the tapes, you can imagine what that scene must've been like -- when Curtis LeMay [the famously zealous Air Force chief] says to Kennedy, "This is worse than Munich."

And of course, he knew what a slap in the face that was to Kennedy, whose father, Joe, was considered a Nazi appeaser before World War II.

Yes, indeed. That is part of that story. Thank you very much.

How does Kennedy respond?

Kennedy does not respond. There's silence. Kennedy says very little to the generals.

One of the things that really fascinates me about that moment, where LeMay says this is worse than Munich, is that it goes right back to a question you asked me at the beginning of our conversation about historical analogies. Iraq, Vietnam, Munich, the Cuban missile crisis, the danger of this sort of thing. But let's look at the reality here.

First of all, the Kennedy administration had been given faulty information by the CIA. They had been told there were no Soviet warheads on Cuba. OK, so what should the president conclude? Perhaps the Joint Chiefs are absolutely right. Act sooner rather than later. Take out the missiles, take out the missile launchers and the missile sites before the warheads arrive. Although in fact several of those Joint Chiefs wanted to go a little further than Cuba, they wanted to go take out the Soviet Union and China as well. They had big appetites. But we now know that if LeMay and the other Joint Chiefs had had their way, and there was bombing and an invasion, the local Soviet commanders who had autonomy would have used those missiles with warheads against the United States. Can I say this with certainty? No. But was there a good likelihood if we invaded and bombed that they would reply? Yep. So that in this instance, "appeasement" averted a catastrophe. The analogy to Munich isn't an analogy at all. People often make these analogies. What is Munich? It's a way of calling a leader like Kennedy a candy-ass. And because of your weakness, because of your policies, everyone will have to suffer. It will lead to an even worse catastrophe than you can imagine. In this instance -- wrong! The diplomatic solution proved to be the correct one.

So during the Cuban missile crisis, "The Fog of War" makes clear that the Kennedys and McNamara acted heroically, and by defying the generals, saved the world.

Yes. You know, I worry for many reasons about being seen as a McNamara apologist. But based on the research that I've done, I do not see McNamara in the same way I saw him years ago. I see him quite differently. I no longer see him as the chief architect of the war in Vietnam. I no longer see it the way that ["The Best and the Brightest" author] David Halberstam sees the Vietnam War, for instance, that it was the product of a bellicose McNamara and a vacillating Johnson. I believe it was the other way around. And I believe that McNamara, throughout the Cuban missile crisis, was a restraining force on the military. And helped keep us out of war.

Now I also believe that McNamara willingly implemented Johnson's Vietnam policies. Why? Why is the question. If he was so opposed in Oct. 2, 1963, while Kennedy was still president, not just to the escalation of the war, but to our continued presence in Vietnam past 1965, how is it that he becomes the enabler in the Johnson administration? How the hell does this come to be? I have my answers. Are they conclusive answers? They aren't. But it does go back to these questions of McNamara's personal code of honor -- if you're rule-bound, when does loyalty to the public, when does loyalty to the republic, when does loyalty to the truth trump responsibility and loyalty to the president. As one Harvard historian, Peter Hall, very kindly said about my movie, it is one of the very few works of history -- and he did consider it a work of history -- that shows clearly the complexity of the decisions that people had to make.

Speaking of McNamara's role as a restraining force on the military, it's ironic -- today, in the Bush administration, the situation is reversed. It's the military commanders who are the voice of reason, and the civilians like Rumsfeld, Cheney, Wolfowitz and the others who are the crazies.

They're like cheerleaders. They're out there with short skirts and pompoms and letter sweaters, urging the country into war. The one military leader in a civilian post in the Bush administration [Colin Powell] has been marginalized because of his reluctance to go to war. It's ironic. It's even funny in a grim sort of way. And it's goddamn frightening.

But perhaps not as frightening as the Cuban missile crisis, when the entire world was on the brink.

Yes. And you don't know whether it was a ploy, of course, a way to wring concessions from the Soviets. But in the middle of that crisis, Bobby Kennedy told the Soviet ambassador, Anatoly Dobrynin, that Moscow had to understand that if there is not some kind of resolution quickly to this, there is a risk of a coup in the U.S. The military will topple JFK. I like to say that we have come to realize that "Dr. Strangelove" is not a drama, it's a documentary.

McNamara speaks most clearly about himself when he's speaking about others. There's a moment in my movie when Johnson gives McNamara the Medal of Freedom at his farewell ceremony and he's unable to speak. And then in the movie he says what he would've said to Johnson if he had been able to speak. He would have said that people should understand that he had reasons for what he did. That there were people who wished for a war with the Soviet Union and Red China, and he was determined to prevent it. And if you like McNamara, if you're sympathetic to him, it's a key moment. If you hate him, if you dislike him, it is seen as one more pathetic excuse among many. But there's a reason why General LeMay is in this movie so prominently, because he represents a dark part of American history that was there, it was real. This was not a figment of McNamara's imagination. He knew all too well what he was dealing with.

Shares