Abu Ghraib prison became famous in Saddam's time as the place where men disappeared. Behind its high, ochre-colored walls and looping spans of barbed wire, prisoners faced miserable living conditions, regular torture, and (in some cases) execution. Now the U.S. military controls Abu Ghraib, calling it the Baghdad Correctional Facility (though no Iraqis I've met seem to be aware of the name change). And for many Iraqis seeking information about relatives detained by the American military, Abu Ghraib is still a place where men disappear.

Abu Ghraib now houses thousands of prisoners. The military will not release specific numbers, for security reasons, but the Associated Press reported that 12,000 people are being held there. Prisoners are pouring into the system: According to Human Rights Watch, in December and January the U.S. military said it was arresting approximately 100 Iraqis per day. Each visit requires two guards -- one to supervise the prisoner and one to escort his family members. The backlog for visitation is months long. Families have no contact with their interned relatives while waiting for that date. Many of the people at the prison that day were waiting to hear whether their relative's sequence number would be read so that they could come back in May for a visit. Others had come in November and were just now able to see their relatives. Some detainees are allowed no visits at all. And some relatives don't even know where their parents, brothers or sons are being held. The system, frankly, is a mess.

Some Iraqis who have been held as security detainees claim they were subjected to ill treatment, including beatings, sleep deprivation and psychological abuse. Most of these allegations are anecdotal and cannot be confirmed. But a variety of human rights and peace groups, including Human Rights Watch, Occupation Watch, Christian Peacemakers, Amnesty International, as well as various Iraqi NGOs, have interviewed former security detainees who have described some kind of mistreatment at the hands of the Americans -- at the time of arrest, during interrogation or during incarceration.

Last week, the U.S. military announced that 17 military personnel, including a battalion commander and a company commander, had been relieved of duty pending the results of a criminal investigation into alleged abuse of Iraqi detainees at Abu Ghraib. The military did not specify the nature of the abuse. But in a separate incident in January, the military discharged three soldiers who had been found guilty of beating, kicking and harassing detained Iraqis at Camp Bucca in the south of the country.

The detainees' living conditions are poor. In Abu Ghraib, most prisoners are housed in tents that offer little respite from cold, wet winter weather and scorching summer heat and provide no shelter from incoming mortar attacks. And they are in the hands of a justice procedure that is, to say the least, highly fallible.

Last Friday, I drove out to Abu Ghraib with my translator Amjad and driver Thamer. I had heard that every day, hundreds of Iraqis gather in front of the prison looking for information about relatives or trying to make visitation appointments. Fridays tend to be particularly busy because, in this predominantly Muslim country, Friday is the day off. We took the freeway west from Baghdad, passing smaller and smaller houses, then scarcely defined shacks cobbled together with bricks, scrap metal and tenting. Farmers scraped away at the chickpea-colored land while kids in ratty frocks and sweat pants chased chickens and each other around the family dwellings.

Off the highway, a small open-air souk (market) bracketed the road leading to the prison. Vendors sold produce stacked in meticulous pyramids. The colors of the oranges, eggplants, lettuce and tomatoes seemed particularly bright against the monochrome of the surrounding area. Past the souk, the road continued through an open plain where piles of dirt and large holes alternately pimpled and pockmarked the ground. We turned into an uneven dirt parking area where scores of cars and pickup trucks squeezed together in barely parallel lines. Eventually, we found a space in one corner of the lot next to a snack cart selling potato chips, candy bars and soda.

In the distance, closer to the walls ringing the prison, I could see a crowd of hundreds of people. We walked along a dirt road toward the crowd and within a few minutes we had become part of it. An Iraqi man in a wool cap and sunglasses stood on a platform (actually, it may have been a car -- the crowd blocked my view) and yelled out numbers that he read from a list he was holding. These numbers represented individual prisoners. Anyone arrested and detained in Iraq gets one of these "sequence" numbers.

Right now in Iraq there are two classifications for detainees: criminal detainees and security detainees. Criminal detainees are those accused of what the military refers to as "Iraqi on Iraqi" crime -- theft, murder, black-market peddling. While these detainees are ostensibly the responsibility of the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), they are increasingly being processed through the Iraqi justice system. Their cases are heard in Iraqi courts and they are incarcerated in Iraqi-run prisons (or, at Abu Ghraib, in an Iraqi-run portion of the prison).

Security detainees, on the other hand, fall under the auspices of the American military. In the words of a military Judge Advocate FAQ sheet: "Under the Fourth Geneva Convention, coalition forces are authorized to detain and intern an individual who poses an imminent threat to the security of coalition forces or the Iraqi state. Additionally, coalition forces may detain and intern individuals who are reasonably believed to have committed crimes against coalition forces."

Frequently, security detainees are people arrested by the military during nighttime house raids. The raids usually happen because the military has received a tip that the occupant or occupants of the home work with the resistance. The military shells out money for these sorts of tips. Not surprisingly, in a country where the massive unemployment problem has left many people broke, false accusations have become commonplace as a way for people to settle feuds and make some dough in the bargain.

But there are tons of ways to get arrested in Iraq these days. As an occupying force, the military has carte blanche. A woman working in the Iraqi Assistance Center, which helps the families of detainees, told me that people often get picked up because they happened to be nearby when U.S. troops got attacked. In the ensuing chaos, the soldiers make sweep arrests, detaining anyone in the vicinity who strikes them as suspicious.

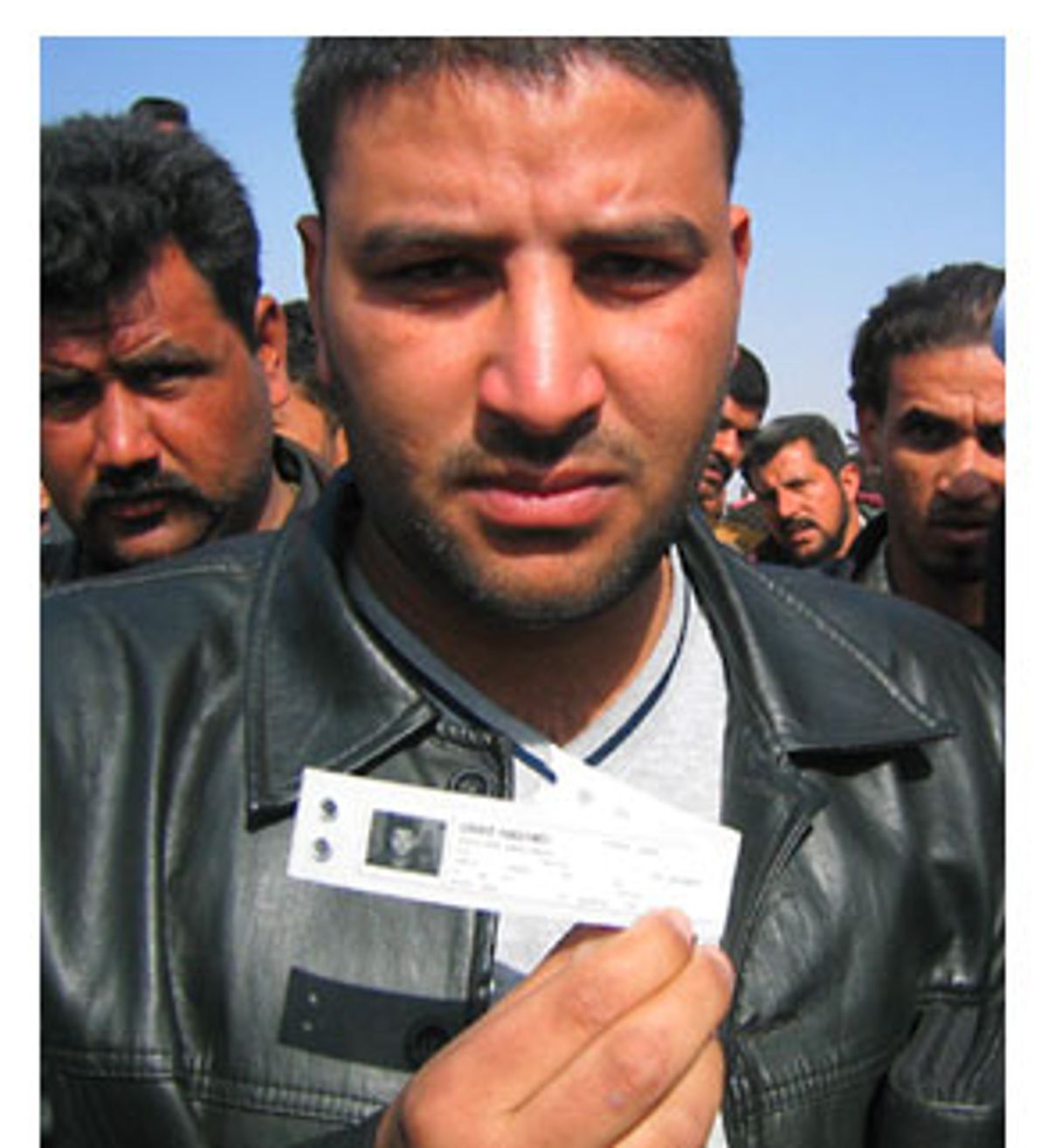

I walked into the crowd in front of the prison and Amjad asked the people around us to explain why they were there. Men of all ages made a gentle scrum around us. An elderly woman with the blue tattoos on her chin that signal she's a Bedouin clutched her abaya around her with one hand and grabbed Amjad's arm with another. A young man who had, himself, been in the prison, started telling his story. Soldiers had stormed his house in Fallujah at the beginning of December. They arrested him and his father and charged them with being part of the resistance. On Jan. 20, they released the young man but his 54-year-old father was still inside. He didn't know why. Neither he nor his father, he told me, had any connection to the resistance. As with all the stories told to me about mistreatment of detainees, I had no way to confirm the truth or falsity of his claim.

Another man started talking. "I was picked up with my brother when the Americans got attacked nearby," he said. "They let me go but my brother's still in there." And another: "My uncle died in the prison four days ago. My other uncle died 14 days ago. Both were arrested four months ago when the Americans stormed the house. They were in bad health. They died 10 days apart. My brother and cousin are still inside." A man next to him held up his wrists to show me his bruises. From being handcuffed, he said. He had recently been let out of Abu Ghraib after a month. His brother was still inside. The soldier who had interrogated the man in prison asked whether he had enemies in the neighborhood. Neighbors kept making claims, the soldier said. Another young man told me a soldier had hit him in the face with a rifle butt during a search of his house. He and five of his brothers had been arrested. Three brothers were out, three still in. It was his 10th trip to the prison to try to get information.

Amjad tried to keep up with translating as I furiously wrote notes. Though I remember the faces of the men telling the stories, I can't match them to the stories themselves. Too much information too quickly. I planned to stay as long as I needed to to check out the stories more thoroughly. Not all of them were entirely consistent and I wanted to weed out exaggeration. I wanted to speak to the old Bedouin woman who still had a hand on Amjad's arm and had begun quietly crying.

As I took down the stories, the man on the platform continued to read numbers. He would announce a date a few months down the road and read the sequence numbers of the prisoners who could be visited that day.

I had been at the prison a little under half an hour, and hadn't had a chance to talk to the old Bedouin woman yet, when suddenly an American voice behind me hollered, "What the hell is going on here?" Iraqis parted to make way for a beefy M.P. in his 40s who appeared at my shoulder. Another M.P., a tall young guy in aviator sunglasses, stood a few paces behind. "Who gave you permission to be here? Did I give you permission to be here? Did you clear it with anyone?" Iraqis I had been speaking with began to fade away from me. While they couldn't understand the words the M.P. was speaking, his bulldog tone of voice provided translation.

I told the M.P. I didn't realize I needed permission to be outside the prison. I was just part of the crowd. "You can't be here," he said. "You have to leave now." When I told him I'd like to get his name first he said, "My name is Sergeant." His helmet identified him as Sgt. Reyes. I asked him what channels I needed to go through to return to the prison, perhaps even to interview him. He told me to speak to the public affairs officer (PAO) for the 16th M.P.s at BIAP (which stands for Baghdad International Airport) -- a military base nearby. But he had no phone number or e-mail for the PAO and no civilian gets onto BIAP without a prearranged escort.

I began slowly walking in the direction of the parking lot. Iraqis who had wanted to talk to me tagged along and I took notes as I walked. Sgt. Reyes popped up at my shoulder again. "I asked you nicely the first time," he said. He may have even believed it was true. He glued himself to my shoulder and we both ambled down the dirt expanse leading toward the parked cars. "Where are you from?" he asked. I was pretty sure he was asking what news organization I worked for. "America," I said. He lowered his voice and began acting conspiratorially chummy. "Listen," he said. "This isn't a good time to be here. We're expecting an attack." Abu Ghraib prison regularly gets hit by mortar shells. In fact, the previous evening the prison had been briefly bombarded. But at that moment, I felt certain that the sergeant was bullshitting me to encourage a hastier retreat. And if he wasn't bullshitting me, he was endangering the lives of the hundreds of Iraqis still lingering in front of the prison by not passing along that information to them.

As it turns out, Sgt. Reyes had every right to give me the bum's rush off the property. When I finally tracked down a military public affairs officer by e-mail and inquired about the policy for press outside the prison, I got this response: "I can confirm that the area you referred to is considered part of the grounds of Abu Ghuraab [sic] and is therefore under military control for the purpose of security and force protection." In the past week, I've spoken to other reporters who've gotten the boot from outside the prison as well -- for the purpose of security and force protection. But there seems to be no consistency in the policy toward journalists outside the prison. A few days after my trip, another reporter I know went to Abu Ghraib. She interviewed Iraqis in roughly the same place I had and never encountered a single soldier. After two hours, she left of her own volition.

Iraqi security detainees do not have the right to representation by an attorney. They do not appear before a judge. After someone has been arrested as a security detainee, he is shunted through a system that is 100 percent U.S. military. I had heard that some security detainees, those considered "high risk," do not have any visitation rights whatsoever. I contacted a military PAO via e-mail and asked for confirmation about this policy. When I didn't hear back, I tracked the PAO down at his office inside the Green Zone convention center. He told me he had made inquiries and been informed that the military would not comment on issues of policy. In other words, the policy is not to discuss policy. I thanked him for his time and walked one flight down to the Iraqi Assistance Center where I posed the same question. The woman I spoke to there confirmed that some security detainees do not have visitation rights. This is a simple fact that gets conveyed to the relatives of those particular detainees. It's not a military secret.

Obfuscation by the military regarding its detention and justice policies is not confined to Iraq these days. What's happening here has strong parallels to the situation of the Guantanamo Bay detainees. Obviously, both there and in Iraq, many detainees are, in fact, guilty. But the justice system they encounter has little in common with the ordinary American standard of investigation and trial. Of course, wartime justice is never going to be identical to peacetime justice, and counterinsurgency tactics are not for the faint of heart. But that is no consolation to detainees and their families in U.S.-occupied Iraq -- many of whom are innocent.

"This situation is like Guantanamo on steroids," said Stewart Vriesinga of Christian Peacemaker Teams (CPT), a faith-based peace group. CPT has been interviewing former detainees and their families to try to shed some light on what happens to security detainees. I spoke to Vriesinga, who was also in Baghdad, over a crackling phone connection. (Land lines in Iraq are still virtually nonexistent. People communicate using satellite phones, U.S.-area code cellphones, or the new oversubscribed Iraqi cellphones. Heavy static and frequent disconnection are the norm with all three.)

Vriesinga said that former detainees regularly describe being hooded, handcuffed and left outside for hours on end (sometimes in the rain) at bases where they are initially taken for interrogation. Accusations of beatings during interrogations are also common. Given the mantle of military secrecy over the entire process, CPT fears that the stories they hear are just the tip of the iceberg.

It's hard to know what to make of the allegations of abuse. I've met many soldiers who I'm sure would never think of abusing their power as members of an occupying force. But the military operates with nearly total impunity in Iraq, and there are an awful lot of soldiers here right now. Many of them are young, and not trained to deal with the situation they find themselves in. They are scared and pissed off by the ongoing attacks on American troops, which kill and maim their buddies and comrades. It's easy to see how those feelings might translate into abuse of men allegedly responsible for the attacks.

A few days ago, I met a man who told me his story of incarceration. When we sat down to talk, he said he had promised his mother he would not reveal his name -- she feels afraid all the time he will be arrested again -- so I'll call him Ali. Like all the other detainee stories that I heard, it was impossible to verify, but it was strikingly similar to many others and, to me, had the ring of authenticity.

Last July, based on a tip that Ali's father was working with the resistance, around 40 American soldiers raided Ali's house in the middle of the night. They broke the door down and cuffed Ali, his two brothers and a cousin using the plastic rip-tie cuffs that have become standard issue for soldiers. They wanted to know where Ali's father was hiding. As it happens, Ali told me, his father died in 1975. (A lifelong neighbor of Ali's family confirmed this was true.)

The soldiers transported Ali and his relatives to a military camp and made them lie on the dirt ground, still cuffed, until the following day (Ali estimates 12 hours). Eventually, soldiers rousted the men, gave them water for the first time, and recorded some basic information. Next, they transported Ali and all the other men picked up during the night to another military installation located in the Dora neighborhood of Baghdad, called "Scania" because it occupies a former Scania company factory. At Scania, Ali was taken into a bare room where a soldier and Iraqi translator interrogated him. The soldier told Ali that he knew he had attacked American troops. He said there was a witness and film shot from a satellite. The soldier demanded to know whether Ali had been paid by Saddam Hussein or was working with al-Qaida. He yelled at Ali, repeatedly calling him a motherfucker. He forced him to kneel, then jumped on his knees and beat him on his head. After about an hour of harassment, the soldier suddenly changed tactics. He told Ali that he knew he was innocent and, if he gave up a name -- someone involved in the resistance -- he would let him free. Ali had no names to give him.

After the interrogation, Ali had the chance to speak to his cousin and one of his brothers who had been interrogated by a different soldier who had treated them with kindness and respect. Later that day, those two were sent home while Ali and his other brother officially entered the security detainee system. They were moved to another camp at BIAP and then, a week later, yet another in Nasariya. On the bus trip to Nasariya, with the late summer temperature nearing 130 degrees Fahrenheit and the bus's air conditioning broken, the soldier on guard in the bus refused the internees water, according to Ali. A young man died of heat stroke, Ali told me, and was taken from the bus halfway through the trip. After a week in the Nasariya camp, Ali was on yet another bus, this one headed for Abu Ghraib. During the trip, a diabetic man died. Though the soldiers on the bus treated the detainees kindly, Ali said they took souvenir snapshots of each other with the prisoners -- a violation of the Geneva Convention.

Ali said he spent a little over a month in Abu Ghraib. Apart from his initial interrogation at the Scania base, he was never questioned. Forty-five days after his arrest, he and his brother heard their sequence numbers read aloud one morning at roll call as part of a list of prisoners being set free. By that evening, he was home.

Ali's incarceration occurred last summer. Since then, the military has implemented some changes in its treatment of detainees. Now, for instance, security detainees held at Abu Ghraib no longer share quarters with criminal prisoners. (Ali described living in a large tent where fighting and theft constituted an ongoing problem.) But accusations of abuse continue, and not just at Abu Ghraib. Just recently Electronic Iraq, an antiwar site that carries many reliable stories regarding the current situation here, published accounts by an Iraqi man and his son who were detained at an unknown base and then at Scania in January. Their stories, as told to representatives of the peace and justice groups Occupation Watch and Christian Peacemaker Teams, include being struck, kicked and deprived of food, sleep and water. Psychological abuse also allegedly took place: The son said that one of his interrogators threatened to take pictures of his wife, mother and sister naked and show them on satellite as a sex film.

At the end of August, the military Judge Advocate established a Review and Appeal Board to help expedite the process for adjudicating security detainee cases. In its FAQ sheet, the Judge Advocate Office states that the board meets daily and considers an average of 100 cases per day and that, since its inception, it has reviewed over 2,500 cases and ordered the release of more than 1,500 detainees. It does not, however, state the criteria for keeping or releasing prisoners. Most of the investigations seemed to be based purely on initial interrogations. When I tried to arrange to speak to someone in the Judge Advocate Office, I was told that it was very difficult and that, if I submitted questions in writing, they might be addressed in one to two weeks. In all fairness, this probably has as much to do with the office's crushing workload as it does with avoiding the press. But, as the policy regarding journalists visiting the prison grounds indicates, this is not an issue where the military invites transparency.

When I spoke to Stewart Vriesinga, he told me that these numbers of detainees currently being released do not mean the situation is improving. They mean that more people are being detained than ever, he told me. And many never make it onto the detainee list at all -- they just get lost in the system. This is particularly true of those held at bases rather than prisons. Right now, the official detainee list hovers between 11,000 and 13,000 people. But CPT believes that number is by no means comprehensive. With so many detainees falling through the cracks, they feel the number is probably closer to 18,000 to 20,000. For families who cannot locate their relatives, he told me, the situation feels terribly reminiscent of the previous regime. A story on the Occupation Watch Web site quoted one Iraqi man as saying, "It was easier to get a visit under Saddam!"

Apart from the military, only the International Committee of the Red Cross has access to security detainees and they do not make their site assessments public. Iraqi and international human rights groups are doing their best to draw attention to detainee issues here, but they often find themselves stymied by the military's invocation of security concerns.

I sat down one night with Hania Mufti of Human Rights Watch to discuss some of the organization's concerns regarding the security detainee system. We met in a nearly empty hotel restaurant and I sipped at a beer while Mufti drank coffee. She had spent the day alternately in meetings and traffic and she seemed drained.

Mufti said that HRW couldn't say for certain how systematic and widespread the abuse was, but that the proceedings against soldiers at Abu Ghraib and Bucca seemed telling. In her experience, most of the complaints dealt with violence and humiliation at the point of arrest (i.e., men getting roughed up, women not allowed to put their hijab on during house raids) and bad living conditions in the camps. They were told of beatings but could not prove they happened.

Mufti reiterated what Stewart had told me -- that, after an Iraqi is arrested as a security detainee, it can take weeks before his name shows up on a computerized list, meaning relatives have no way of knowing what's happened to him. (During this period detainees are held at an interim interrogation facility like Scania. Many people, like Ali's brother and cousin, get released almost immediately and their name never enters the system.) If the detainee is not released, he'll be shipped to a more permanent facility like Abu Ghraib to wait for his case to be reviewed. The criteria for when or whether a detainee gets released is uncertain. Ali believed, for instance, that he and hundreds of others had been released one day because an army general visited Abu Ghraib and witnessed the severe overcrowding. The specific criteria for initial internment is equally unknown, Mufti told me, because it falls under the rubric of "rules of engagement" and, at any given time, rules of engagement are military secrets.

I asked Mufti, as I asked just about everyone I spoke to about military detainees, what would happen to the system after the handover of power to the Iraqis at the end of June. Though the U.S. military will remain in Iraq, theoretically, they will be here only to support the Iraqi security structure. At this point, no one seems to know what power, if any, the military will retain in regards to detaining Iraqis. A military PAO I contacted told me that the issue has yet to be resolved. It's hard to believe that this whole system will just end. That after an attack on troops, for instance, there will be no sweeping arrests. More and more, though, Iraqis see July 1 as a date of liberation. If the U.S. continues to act in any way as an occupying force, the consequences could be dire.

(Today's events in Iraq acted as a disturbing example of just how antagonistic Iraqis have become toward American troops. In my house in Baghdad, I watched footage from the aftermath of the bombings in Karbala and Baghdad's Khadamiya neighborhood on television. At one point CNN cameras captured American troops arriving in Khadamiya to restore order. Iraqis responded by hurling rocks, bricks and even chairs at the soldiers, necessitating their withdrawal.)

The Iraqi Assistance Center inside the Green Zone tries to help family members of detainees who have traveled from all over Iraq and even neighboring countries in search of information. They fill out a form with the detainee's name and date of birth, then make an appointment to return in two weeks to find out the detainee's sequence number and charge. Oftentimes the information they get is out of date. A lawyer I spoke to told me that he had gone to Abu Ghraib on behalf of a woman who wanted to find out whether she could visit her husband. At the prison, the lawyer was told that the man was a high-risk detainee and had no visitation privileges. When the lawyer went to his client's house to impart that information, he found the recently released prisoner sitting on his living room couch.

In the al-Mansour neighborhood, the half-built al-Rahman mosque (the largest mosque in the Middle East) hovers over the landscape like a rising minareted moon. Even the neighborhood's prodigious mansions look like dollhouses against such a backdrop. One of the nine Baghdad city council offices sits on a street right in front of the mosque, almost beneath its shadow. People refer to this office as "Orfalie" because, until the war, the building housed the Orfalie Art Gallery and a blue and white hand-painted sign identifying it as such still hangs over the door, behind the high cement wall that shields the front of the building from the street. As with any government office these days, armed Iraqi guards patrol around the barrier and search people entering the building.

In the Orfalie waiting room, I met several women who had come seeking information about husbands and sons. They sat in a row of chairs against the wall and, when the person in the last chair got up to meet with a council representative in an office, everyone else got up too and moved down a chair. One by one the women told me their stories. Husbands and sons arrested for reasons the women didn't know. What had they done, the women wanted to know. How long would they be held. Why couldn't they see them. One woman began crying. Her little daughter patted her comfortingly on the knee. "When we get rid of Saddam," the woman said, "we feel happy because this is a new time for Iraq. Now I hate the Americans."

Shares