The problem with Hollywood today isn't that there are no movie artists. The artists are always there, fighting to make good movies or, sometimes, fighting just to work. The problem is that there are no talented hacks.

There are plenty of hacks, anonymous directors who can turn out anonymous movies that will do enough business to keep them employable. But the type of hacks the studios used to employ, the ones who could be counted on to turn out the cleanly made, entertaining movies that occupy us in between the truly remarkable ones, don't seem to exist anymore. That may be because what they could be depended on for -- coherent, emotionally involving storytelling -- is no longer something that matters to the studios at a time when most mainstream movies have been reduced to spectacle.

The new western-cum-swashbuckler "Hidalgo" is the sort of movie that Hollywood once could have made in its collective sleep. Based (loosely, I'm betting) on the life of Frank T. Hopkins, a cowboy who rode his mustang Hidalgo to victory in numerous long-distance races, the picture tells the story of Frank and Hidalgo's entrance into the Ocean of Fire, an endurance race across 3,000 miles of the Arabian desert.

The filmmakers must have realized that a race across a barren desert might get tedious to watch, so they've introduced a subplot about an Arabian princess (Zuleikha Robinson) who aids Frank to prevent the victory of a prince to whom she has been promised in marriage if he is victorious. It's hokey, sure, but it's also exactly the sort of damsel-in-distress scenario that's perfect to get the engine of an adventure story revving.

Frank is invited to enter the race because its sponsor, Sheik Riyadh (Omar Sharif), is offended by Frank's claim that Hidalgo is the greatest horse in the world. He wants to prove that his purebred Arabians are superior horses to a wild mustang. I'm waiting for someone to start complaining that the movie is anti-Arab (surely the Village Voice, which decried the "racism" in "Freaky Friday," can't resist, can it?). It's true that the Arabs are portrayed as the threatening other, and that has an unfortunate resonance in the post-9/11 world. But they are in the movie tradition of inscrutable villains, and they're outdone in villainy by Louise Lombard as the British aristocrat who has her own reasons for winning the race.

If there's any threat to Arab sensibilities in "Hidalgo," it's this: The Muslim prohibition against ham will never stand as long as Omar Sharif is acting. It's too bad the movie doesn't allow him some more mischievous charm. He needs to be an authority figure who's amused by his own power, a bit of a joker (which is the way Jeff Chandler played Cochise in the great 1950 western "Broken Arrow"). Instead he's used as, well, as Omar Sharif. His presence is meant to be enough.

The biggest problem with the whole American-Arab rivalry is that the moviemakers fail to exploit what should have been catnip for audiences: the battle between mutts and aristocrats. Frank, the cowboy, and Hidalgo, the untamed mustang, are heroes because they represent the mongrel nature of America and our instinctive distrust of the highborn and highfalutin. That's the essence of the breezy disrespect for authority that characterizes the great comedies and gangster movies and westerns of our collective moviegoing past.

It's a good joke when Frank addresses the sheik as "pardner," and finally, a sign of respect, too. It should be a great joke that the sheik turns out to be a devotee of western pulps. For all his aristocratic pride, even he can't resist the myth of the American West. But the filmmakers, as with almost everything else in the movie, don't squeeze the potential juice from it.

So many mainstream movies today seem like nothing but concept, pitches for movies that haven't been fleshed out, and "Hidalgo" is no exception. It's a manqué of a rousing adventure tale and not the real thing. You're constantly aware of the gulf between how the movie wants to excite you and the halfhearted execution.

The director, Joe Johnston, has done some moderately entertaining work on "The Rocketeer" and "Honey, I Shrunk the Kids," and the screenwriter, John Fusco, has one of the few good westerns of recent years to his credit, "Young Guns II" (directed by the fine New Zealand filmmaker Geoff Murphy). Their work here is both sluggish and rushed. We get, as we should in a western, some lovely shots of horses in vast landscapes, but we're never really given the chance to drink anything in.

The dialogue scenes feel perfunctory, which would be all right if we were dazzled in the action scenes. Johnston, though, brings them no particular inventiveness, no tightness or superior display or craft. The sequence that should be the movie's action high point, Frank's rescue of Princess Jazira from the fortress of the evil rival who has kidnapped her, has no more distinction than anything else. Even when Johnston and his cinematographer, Shelly Johnson, come up with a good image -- Frank running along a latticed overhang paralleling the movements of Jazira racing Hidalgo seen below him -- they toss it away. (This part of the plot is sabotaged beforehand anyway. When Sharif announces that his daughter would have to be murdered if she were ever "dishonored," you wonder why, when she's kidnapped by his enemies, he doesn't just write her off as dead. The script doesn't allow the character any disjunction between his medieval sense of honor and his instincts as a father.)

There's also a sort of useless prologue, with Frank witnessing the slaughter of Indians at Wounded Knee and retreating into a bottle and employment in Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West Show. It feels like a sop to contemporary sensibilities, as if we had to be reminded of the persecution of the Indians before we could enjoy an adventure tale.

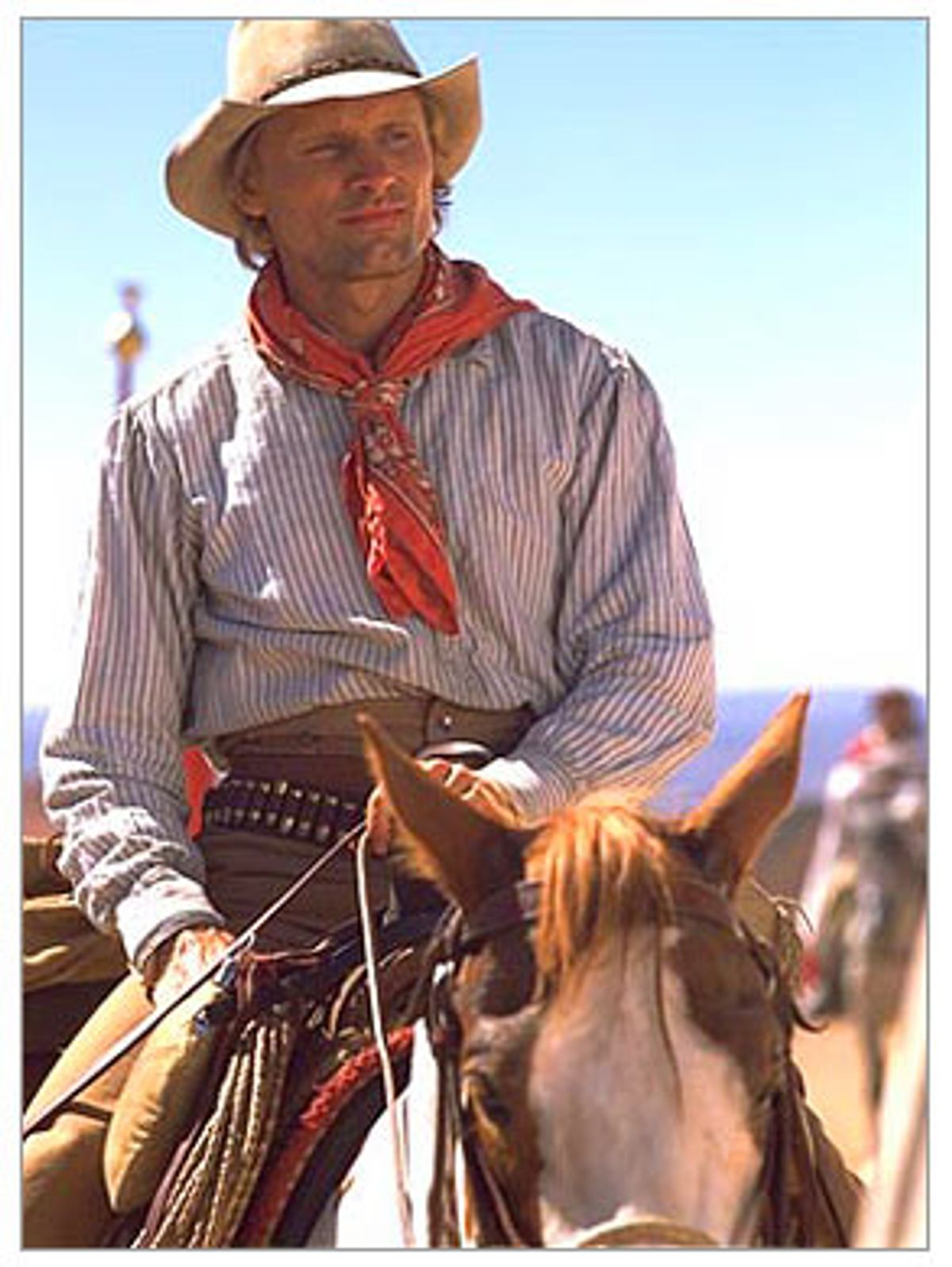

The slight hold that "Hidalgo" does exert is thanks to Viggo Mortensen. In his early screen appearances, Mortensen seemed so recessive it was as if he couldn't be bothered to act. As the hippie who seduced Diane Lane's housewife in "A Walk on the Moon," Mortensen showed some laid-back charm. And as Aragorn in "The Lord of the Rings" trilogy, Mortensen entered the realm of movie heroes who could be commanding without resorting to boasting. (The moment in "The Return of the King" when he kneels before the Fellowship of the Ring, a moment when a leader acknowledges his power by acknowledging its limits, is one of the great heroic moments in all of movies.)

In "Hidalgo," Mortensen plays the quiet Westerner, the kind who doesn't say much and lets his actions speak for him. It's the sort of role that usually invites stolidity, the kind that knocked the sexiness right out of Gary Cooper. Mortensen escapes that stiffness. He's a charming presence in "Hidalgo," wearing the sort of long hair that can make a cowboy seem like an early version of the hippies who set out to commune with nature, and with an understated wit that keeps him from being too much of a Boy Scout.

Mortensen benefits from having a good partner, the gorgeous painted brown-and-white mustang cast as Hidalgo. Johnston uses the horse in all sorts of reaction shots, most of them for comedy. But the cumulative effect of all those moments is to make you feel that Frank and Hidalgo are able to communicate with one another. Hidalgo is much more of a character here than Seabiscuit was in that disappointing picture. (That makes a weird sort of sense, if you remember, as David Denby slyly pointed out in his review of "Seabiscuit," that Seabiscuit's lineage was as grand as that of another Depression hero, FDR.)

The lost opportunity of "Hidalgo" isn't that it fails to live up to its potential for romantic adventure, but that it fails to dig into the romance between man and horse that's at the heart of the story. We're used to seeing western heroes rescue women from villains and stand up for the weak who can't stand up for themselves. This must be the first western in which the hero, prior to dispatching a bad guy, announces, "Nobody hurts my horse."

Shares