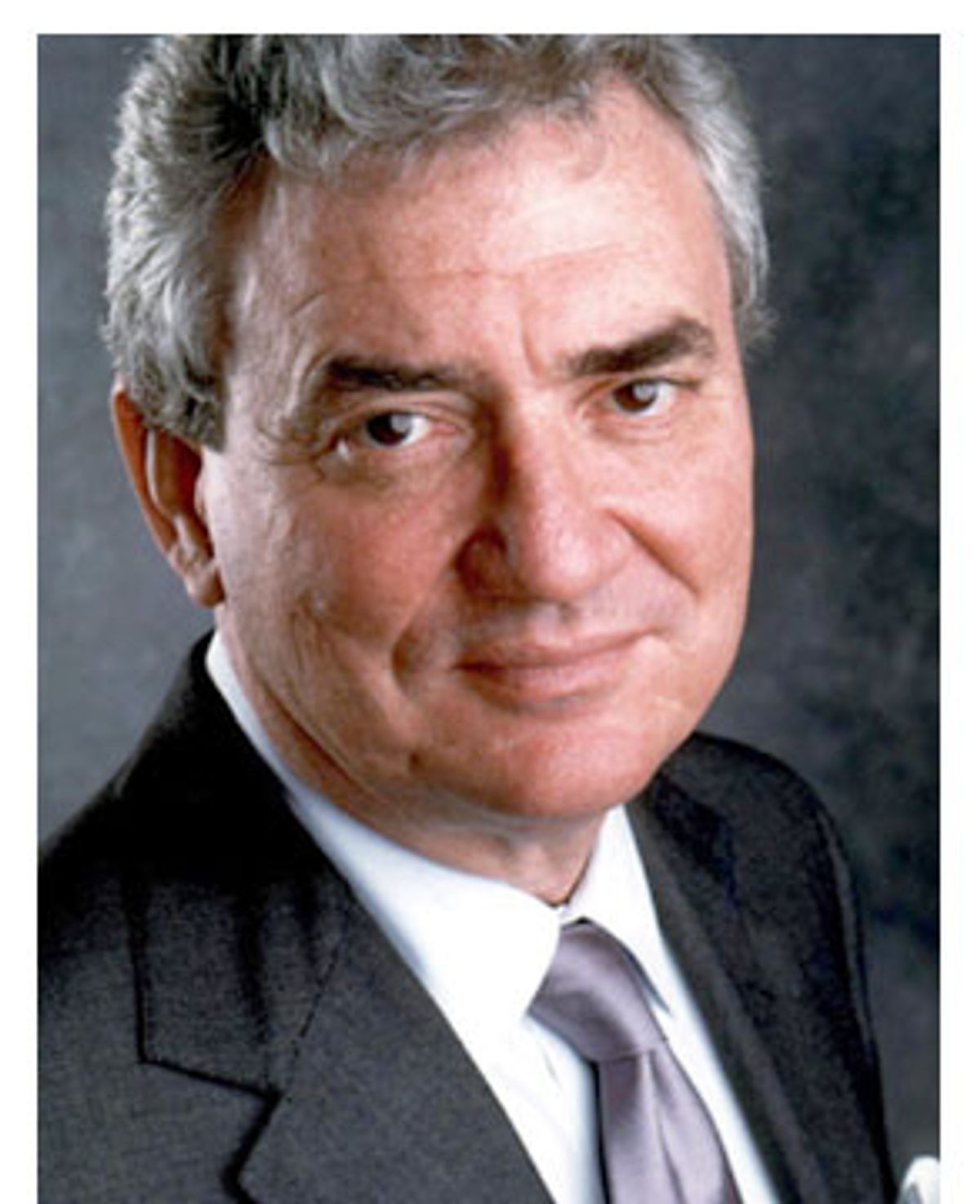

Nearly a year after resigning from the New York Times in the wake of the Jayson Blair plagiarism scandal, former executive editor Howell Raines delivers his side of the story in a new article for the Atlantic Monthly magazine. But it's not Blair whom Raines has in his sights. It's his old newsroom.

In a lengthy piece set for the May issue but released to reporters Wednesday, Raines at times butchers the newspaper he spent nearly his entire adult life working for. Assailing what he saw as the paper's slow-footed approach to covering the news and reluctance to seriously explore pop culture, Raines probably says nothing his former underlings didn't hear while he ran the newspaper. But for Raines to make his criticism so publicly, and for his jabs to be so sharp against his predecessor, Joseph Lelyveld, and indirectly against his own successor, Bill Keller, is sure to set off yet another round of Raines-bashing inside the West 43rd Street newsroom.

Raines is used to it. "I'm not a person who is easy to please or eager to please," he writes.

Considered to be among the most gifted journalists of his generation, Raines became the first executive editor of the New York Times ever to resign under fire, following an internal newsroom revolt last spring. It was a spectacular fall from grace. The hard-charging editor took over the paper in September 2001 and tried to push through dramatic changes, determined to raise the "competitive metabolism of the newspaper." That effort, along with his often arrogant style, turned some of the staff against him. And when word got out that Blair had concocted all sorts of stories that were not only printed in the Times but also earned him newsroom promotions, Raines became a magnet for discontent.

In the end, Raines suggests he simply asked too much, too soon from his staff: "As a result, I kept the staff outside its zone of comfort for more than nineteen months, continually ramping up the demands even as Arthur [Times' publisher Arthur Sulzberger] was responding to the advertising recession by freezing our budget to nearly pre-9/11 levels. When Jayson Blair's violations became public, I had no reservoir of good will on which to draw."

Soon after he left the Times last June, Raines went on "The Charlie Rose" show and bemoaned the staff resistance he encountered as a "change agent" who was determined to confront the newsroom's complacency. When introducing Raines' successor to the Times newsroom, Sulzberger answered, telling the assembled troops, "There's no complacency here -- never has been, never will be."

In the Atlantic Monthly, Raines returns the volley: "I can guarantee that no one in that newsroom, including Arthur himself, believed what he said. It was a ritual incantation meant to confirm the faith of everyone present in the Times's defining myth of effortless superiority."

Raines then runs through examples of how the Times under his predecessor had ceased to be superior:

And then Raines zeroes in on the Times newsroom. "For people who have worked at other newspapers, the biggest shock upon coming to the Times is that the level of talent is not higher than it is," he writes. At another point, he adds: "At the Times, as at Harvard, it is hard to get in and almost impossible to flunk out."

The fact that it's possible to coast at the mighty Times is the worst-kept secret in journalism. And readers would be foolish to think the resistance Raines encountered was not real. But Raines fails to explain why. Why, if reporters or editors are bright and ambitious enough to be hired by the most important newspaper in America, is there some sort of collective desire, as Raines suggests, to suddenly sit on their asses all day once safely on the Times payroll?

"A large percentage of Times reporters and editors opt out of meritocratic competition within a couple of years of joining the paper -- in some cases within a matter of months," he writes. And he notes the newsroom is divided among "the culture of achievement and the culture of complaint." But again, Raines doesn't adequately explain why America's premier newspaper would attract or create so much dead wood.

Also confusing is Raines' pride in the paper's journalistic response to 9/11: "In thirty-nine years of newspapering I've never seen so large a staff rise to so high a level of effort and intensity for so long a time." But he'd just spent a few thousand words describing how listless so much of Times newsroom was when he took over in September 2001.

As for the Blair scandal, Raines surprisingly skims over the incident; his recounting doesn't come until 16,000 words into his 20,000-word opus. One of Raines' main points is that he was kept out of the loop about Blair's failings. (It appears Raines' No. 2, managing editor Gerald Boyd, was the highest-ranking member of the newsroom to be briefed on Blair's poor status before the young reporter's meltdown. But Boyd, who was forced to resign alongside Raines, never told his boss about the situation.)

Raines points out that as the controversy raged on, he appointed a team of reporters to uncover the truth about Blair's crimes against journalism and ordered them to explain the whole saga in excruciating detail in the pages of the Times (14,000 words in all; none of which Raines saw before they were published). From his perspective, the team did not adequately address for readers the issue of how or why Raines remained in the dark about Blair's ongoing personnel problems. By not making that point clear in its exhaustive report, Raines suggests his fate was sealed.

"I read the story in sections as the day unfolded, and I knew at that point that I was unlikely to survive," writes Raines. "The article did not pursue the one area of reporting that might have worked in my favor -- how and why critical information about Jayson never reached me."

As for interesting omissions in the Atlantic article, there's no mention of former Timesman Rick Bragg, whose own newsroom behavior cost Raines dearly. A close friend of Raines', he had been suspended for not crediting the work an unpaid intern had done on a story that appeared with Bragg's byline. As the story mushroomed, Bragg's response was, essentially, that everyone at the Times did it. When that provoked an uproar among his colleagues, Bragg resigned. There's no evidence Raines knew about the corners his friend had cut, but the suspicion inside the newsroom lingered that some members of Raines' star system were allowed to play by a different, more lenient set of rules.

There is also no mention of Raines' heavy-handed -- and apparently unprecedented -- decisions to kill two sports columns. They had taken issue with Times editorials pushing Tiger Woods to take a stand on whether women should be allowed to join the prestigious Augusta National Golf Course. Raines eventually backed down and published the columns, which in the end only highlighted how timid the essays were to begin with.

Elsewhere, there are a couple of short, curious passages that cry out for a fuller elaboration from Raines. For instance, among the many internal newsroom hurdles he encountered on taking over as executive editor was "a small enclave of neoconservative editors was making accusations of 'political correctness' in order to block stories or slant them against minorities and traditional social-welfare programs." Raines makes no reference to whom the editors were or which stories in particular they tried to block. The charge runs counter to conservative critics who insist the paper's editors slant stories to the left.

Lastly, in a bit of revisionism, looking back on the Times coverage of accused spy Wen Ho Lee, Raines suggests the paper was not open enough in dealing with the criticism the paper endured. Pre-Blair, the Lee story stood as perhaps the Times' biggest embarrassment of the last quarter century, as both the news pages and the editorial page, which Raines oversaw at the time in 2000, badly overhyped the accusations against Lee.

"Neither the Editors' Note published by the news department on September 26, 2000, nor the editorial that I wrote two days later had sufficiently explained to our readers how the Times had erred in its reporting and commentary," he writes.

Maybe that's because, still crouched in a defensive mode, the editorial Raines wrote regarding Lee barely even acknowledged that mistakes were made, let alone explained to readers how the Times had erred.

In general, now that he's away from the game, it's become easier for Raines to see his mistakes. But if he's looking for sympathy, he probably won't find much inside his old newsroom.

Shares