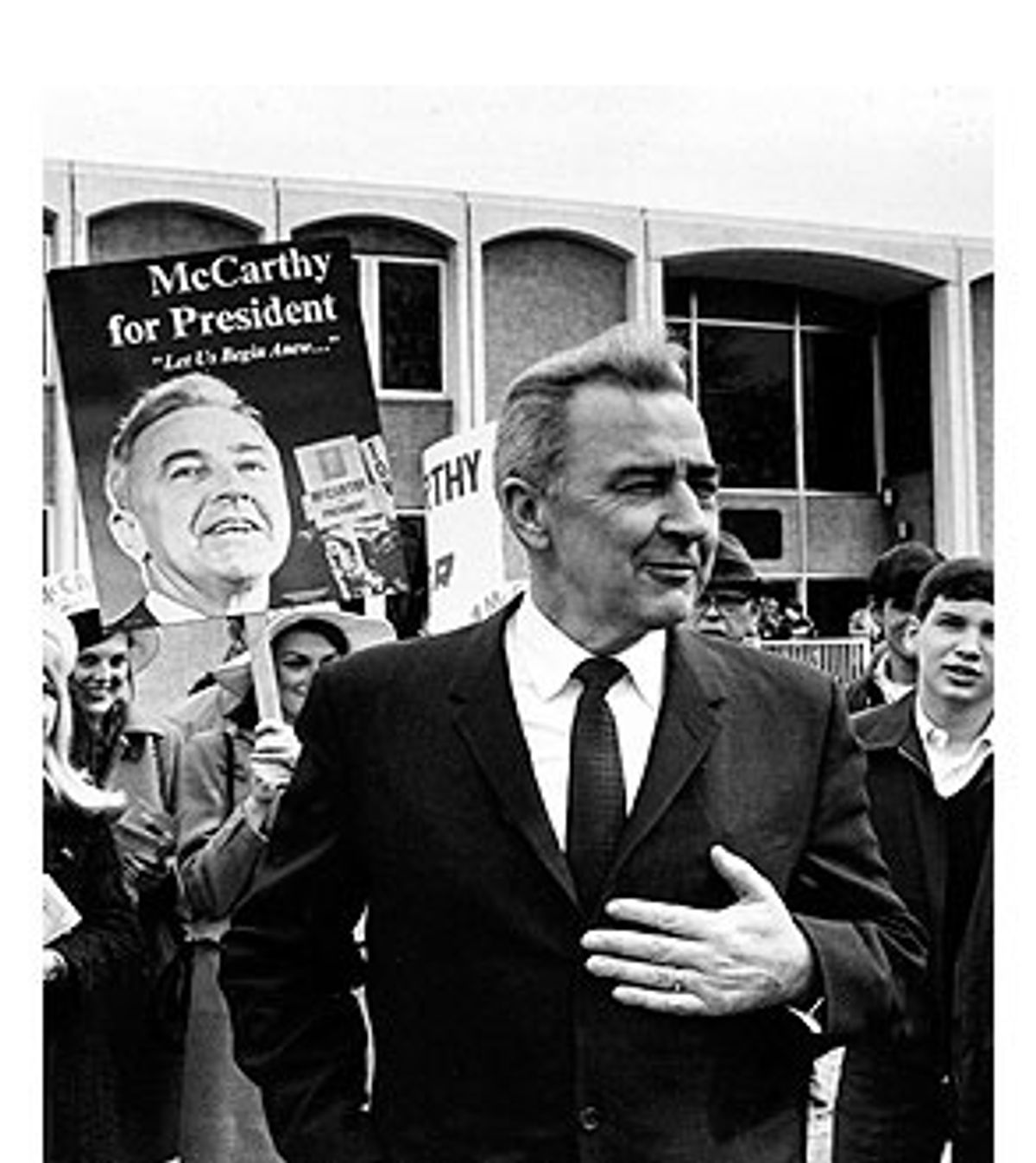

At the end of November in 1967, when the Vietnam War seemed at the point of no return, with chaos on campuses and violence in the streets of American cities, Sen. Eugene McCarthy did what in those days was unthinkable: He challenged an incumbent president for the nomination of their party.

Running against Lyndon Johnson was not the first time Gene McCarthy had shown iconoclastic courage. In 1952, at the height of Sen. Joseph McCarthy's popularity, when not a single senator would step forward to debate the subversive-chasing demagogue, 35-year-old, second-term congressman Eugene McCarthy came forward to oppose Sen. McCarthy (no relation) on the Radio Forum of the Air. Throughout the 1950s and '60s, Gene McCarthy sought to curb the influence of the CIA and the military-industrial complex on American foreign policy, and as a senator he led the fight to extend Social Security coverage to the mentally and physically disabled.

But after 1968 McCarthy baffled many of his supporters and colleagues by choosing not to run for reelection to the Senate in 1970, running a quixotic campaign for president as an Independent in 1976, then running as a Democrat again in 1992 at the age of 76, and, not least, by endorsing Ronald Reagan in 1980.

Now 88 years old, McCarthy continues to write and speak about politics and occasionally compose poetry, a serious avocation since the last of his 12 years in the Senate from 1959 to 1971. He was the subject of a Calvin Tomkins profile in a recent issue of the New Yorker. He has also inspired a controversial new book, "Eugene McCarthy: The Rise and Fall of Postwar American Liberalism," by Dominic Sandbrook, a British scholar whose research on McCarthy was funded in part by the Lyndon Baines Johnson Foundation. The book takes a harsh look at McCarthy's place in the pantheon of American liberal politics and questions whether he was the template for Ralph Nader in 2000. Sandbrook writes that McCarthy was "a complicated and contradictory man, and few of his colleagues felt that they really understood him." He also suggests that McCarthy's political odyssey somehow "reflected the rise and fall of the liberal consensus between the 1940s and 1960s." For Sandbrook McCarthy represents both the intelligence and integrity of American liberalism at its best as well as its self-defeating arrogance. In 1968 McCarthy's cool, understated political style would be dramatically pitted against the ambiguous, romantic populism of Bobby Kennedy -- a rival McCarthy decades later still considers untrustworthy.

However one sees McCarthy -- as a tragic figure, as a hero standing alone against the escalating war in Vietnam, or something in between -- the man will undeniably go down in history as a pivotal political figure at the burning center of one of America's great tests of fire. As the country suffers in the flames of another tragic, unnecessary war, his observations about American leadership and foreign policy again seem particularly salient.

Today McCarthy divides his time between a farmhouse in Rappahannock County, Va., and a retirement home in Georgetown, in Washington, D.C. I caught up with him in the latter venue, which he describes as "a cruise ship on the River Styx." Like the walrus and the carpenter, we talked of many things; the current presidential campaign stirred him to comment on President Bush, whom he regards as a "usurper," the Nader campaign and third-party politics, as well as his own legendary 1968 campaign and his complicated relationships with Bobby and Jack Kennedy.

You've called President George W. Bush a pretender. Why?

Well, he didn't win. It's hard to know what the process should be called because it's an unusual process. Bush is sort of a usurper. He seized the castle. So we have a historical experience that no one else has had, watching a pretender in a democratic society. And we need to watch this because we don't have any good historical record of a pretender in a democracy. We could keep track of royal pretenders -- like the Cavaliers, you know how they're going to act -- but you never know what will happen in a democracy. I'm beginning to think they all act the same way in every case. They distract people, start a war, then the pretender leads us into battle.

I mean the whole Bush takeover was really unconstitutional. And it's a potentially dangerous thing. If you have control of the military in this country, you can do almost anything. Who's going to stop you? The Supreme Court? Stalin said, "How many divisions does the pope have?" You can say that same thing. In a showdown the party out of power doesn't have any power. If someone wants to say "goodbye, Constitution," you can't stop them.

Why not?

Well, it's pretty hard to have an uprising in this country.

Do you think that's getting to be a concern in our elections?

I think so. Almost every society has some source of the ultimate judgment -- witch doctor, high priest, or in medieval times you had the church as the ultimate arbiter. Kings had to be crowned by the pope. We don't have that. We have the Supreme Court whose procedures de Tocqueville said were judicial but its powers were legislative. He called the court the most powerful legislative body of any democratic society. He meant that the Supreme Court can say, "This is the law." And where are you going to go? It's the law. Dred Scott? Plessy vs. Ferguson? Where are you going to go? It is the law. There is no place to appeal beyond it.

In 2000 you had the election turn on the votes of five Supreme Court justices and the winner take all. Winner take all should be abolished. It's one of those processes the framers of the Constitution accepted because they were afraid of secession. So they made concessions to small states -- not only to have two senators but in the actual electoral process, too. They came up with the idea of winner take all. First, the small states said that's good, we'll have more power. Then everybody said, yes, let's have winner take all. That was operative in Florida, so the results really depended on five Supreme Court justices -- all were Republicans -- and winner take all.

You've said the two-party system is a danger and should be addressed. But you want to get rid of Bush.

Bush is a good enough reason not to do anything with a third party this time -- though I think we need one.

Why?

Well, with the Federal Election Law and the FCC, the two parties have gotten beyond the Constitution. In 1975 Sen. Jim Buckley and I brought a case to the Supreme Court [Buckley vs. Vallejo] charging that the Federal Election Law violated the First Amendment -- freedom of speech and assembly -- which it did, you know. And Gerald Ford acknowledged it before he signed the bill. He said, "I think it's unconstitutional, but I'm going to sign it anyway because I believe in the two-party system." And so the First Amendment fades into the distance. Even the Supreme Court justices said, "We still believe in the First Amendment unless it does something to the two-party system." So in this area there isn't an appeal beyond the Supreme Court.

In the mix of American politics the two-party system is the most dominant, the most absolute. But you've got other things, too, slogans you're not supposed to challenge. Like free trade. You can't have a real debate about free trade. Or immigration. You build up these protected areas where the Constitution doesn't really apply. Something like NAFTA, you know; who's going to argue about NAFTA? And so you had five presidents or ex-presidents lined up on the White House lawn, and they all said we believe in free trade. They were having their picture taken and Colin Powell came dancing out of the White House and he said, I believe in it too. Once you've accepted the two-party system or free trade or open immigration ... you can't get the press to pay attention to these institutional disorders. But it's critical that they be attended to.

Why does the press abdicate its role, its responsibilities here?

When we were planning the case for free speech and politics, one press guy after another said this is a two-party country. And then the Supreme Court says the same thing. They didn't literally say it, but their actions implied they'd accepted the superiority of the two-party system. That's where we are; we operate in a kind of unconstitutional system where the only alternative if there's trouble is military action, because there is no absolute appeal anymore. It's who's in power, and as the Republicans said, we've got the Supreme Court.

Since you're so critical of the two-party system, what do you think of Ralph Nader and his run this year?

He did so much early in his career against General Motors, so much to establish some control over the big corporations. But now he's like the March of Dimes, looking for another cause after polio. Campaign reform and congressional reform are undeserving causes. I'd like to see him concentrate on corporate reform. It's not getting the attention of the two parties; because of the Federal Election Law, they're both so dependent on corporations that neither party is in a position to take on the corporations.

How does television influence the political process?

Buying time is mixed up with this. When we were running in the Indiana primary in '68, we had to buy all of Chicago. We said we don't want all of Chicago; we just want Indiana. Can't do it, they said, you've got to buy Chicago. You could do it or not. But the process forces you to use television. And to get the television in northern Indiana, you have to buy Chicago, or to get southern Indiana you have to buy part of Ohio and Kentucky.

There are other abuses, you know. In her autobiography [the late Washington Post publisher] Kay Graham says she told her people [in the newsroom] to go easy reporting on [President Nixon's invasion of Cambodia] because she was afraid Nixon might take away some of their electronic permits.

Why do you think no one called her on it?

Well, they talk about what a wonderful newspaperwoman she was. Basic corruption, you know. I always hoped Nixon would take away a couple of those licenses. Kay was also reported as saying that she wanted to play down [the killing of student protesters at] Kent State because she thought it might stir up the people. Well, the people should have been stirred up. You know, it was like the Dreyfus case. I think the media said don't stir up the people and they let it fade like a one-day news story.

When you first ran for Congress in 1948, you campaigned for national healthcare. Why is it still pending?

Civil rights was a big issue, too, and full employment. All these things were neglected during World War II, and we were trying to catch up. [Republican Sen.] Bob Taft proposed a program covering catastrophic illness, and the Democrats said we're not going to give you that because we're going to get total coverage. That was more than 50 years ago, and we're still talking about it. We had the strength to do it then, but the Democratic leadership, especially labor, said we're not going to give them [the Republicans] a piece of it.

Do you think John Kerry ought to run hard on healthcare this time?

Well, I think he makes a negative case on that. He makes a case against the Republicans that the Democrats are going to do better. I don't know whether he should come out for a comprehensive program. They've kind of hurt themselves by not going for catastrophic, but I think there is enough room to make a good case for the Democrats to do something about it. Some of this goes back to Lyndon's Great Society. I think the error of the Great Society program was that it took full responsibility for education, crime, medicine, health -- all those things -- when half of them have to be administered locally. This is true about crime. You can't have the FBI handling all the crime in the country. You can't have the federal government handling all of education. We should do things like aid to the states but fix responsibility for things like high school education, grade school education -- equalization -- then have them administered by the states. Crime, too. As it is, the federal government is responsible for everything except garbage collection.

You put Eisenhower's historic farewell address -- his warning about the growing power of the military-industrial complex -- in the Congressional Record, didn't you?

I did, yeah. No one else would put it in. I thought some Republican would rush to do it -- I waited a week or so. No one else would move. The speech clearly laid out the dangers of the military-industrial alliance in American life -- with Ike's name on it, you know. I thought it was important -- still do.

Do you think the military-industrial complex is even more dangerous today?

De Tocqueville said democracy can't stand a long war or a military establishment, that its nature is to extend its [domain] in a war. And democracies don't want to be alone; they want other democracies to join them if they're fighting a war. If another democracy doesn't join them, why, they're uneasy. They can't explain it away. It's a rejection.

Is that where we are now, with the Bush administration's occupation of Iraq?

Language is being changed -- that's the first thing. They talk about empire. De Tocqueville says democracies can't have an empire. But the concept of the Bush people is really of an empire.

In your 1967 book "The Limits of Power," you said that the country needed to get back to Jefferson and the other founders' idea of having "a decent respect to the opinion of mankind." When did we get away from it?

I think the critical time of decision was when we elected Eisenhower and he appointed John Foster Dulles his secretary of state. In one of Dulles' early speeches he laid out the ground for what's happening now, the moral ground for controlling the world. He said, if you're good, we'll be good to you; if you aren't good, we're coming. It was like Cromwell saying, "I'm a righteous man and you have to do the work of the Lord sometimes." It's hard to explain, but the basic thing was something like the immorality of neutralism. Kennedy operated a little like that in his inaugural. It was almost a restatement of Dulles and Cromwell. "We're going to straighten you out." I was standing there on the Capitol steps, and [House speaker] Sam Rayburn came by, and old Sam said, "That's a good speech."

But it was building before then. World War II was fought under the direction of the War Department. When the 1947 appropriation came out -- the year before I got elected to Congress -- they called it the defense appropriation. Later on, I tried several times to find out whose suggestion it was, but no one knew. It went in as the War Department and came out as Defense. We don't declare war anymore; we declare national defense -- [during the Cold War] the Russians did it, too, all for defense. It makes it easier, at least for a democracy, to ask for money. If you say you want $300 billion or whatever it is for war, they say, "Well, where's the war?" But if you say defense, it's everywhere. Now they say, "How much do you want for terrorism?"

How does your old nemesis during the Vietnam War, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, compare with the present Pentagon chief, Donald Rumsfeld?

They're different. Rumsfeld is kind of aggressive politically and McNamara was intellectually aggressive. McNamara was bad because he had all the arrogance of the automobile industry and his own arrogance. You know, I can think of everything, I make no small mistakes -- and he didn't know any politics. My position is that the secretary of defense should be someone with political experience.

I want to ask you about your decision to challenge Lyndon Johnson for the presidency in 1968. Over the years many have rushed to explain it -- a recent biographer called it opportunism. Could you talk about how you came to become a candidate in November of 1967?

I thought someone ought to challenge this ridiculous war, and I also thought a great deal about the domestic agitation and confusion. And I realized the Senate wasn't going to do it when [it failed] to repeal the 1965 Tonkin Gulf Authorization. The repeal got five votes. That was in '67; it wasn't like 1965 when people still believed the Tonkin Resolution was the real thing. And I said, I guess a number of times, that one of the principal responsibilities the Senate had is to be involved in a serious way in foreign policy, and that the ultimate act of foreign policy is war. Therefore the Senate had a special responsibility when war comes to say, "Do we want it? Is it in the interest of the country?" And I thought that we'd reached that point and passed it and, well, it sounds self-serving, but if the Senate wouldn't do it, that didn't excuse me for not doing it. Because one senator could take responsibility for the whole body if he wanted to fulfill his constitutional duties.

Was there a personal element in your decision to run? Concern about the young people and your own children?

Well, they were part of it. Marching in the streets and nothing happening. Write a letter to the president, write a letter to your senator, write a letter to yourself. I wouldn't sign some of those letters. I said it would turn the Senate into a garden club. Send ourselves a message.

In Steven Vincenzi's book "The Rules of Chaos," he said by running against President Johnson you exposed yourself to the two things a man is least willing to face: losing his livelihood and looking like a fool. Is he right?

We knew we were going to be ridiculed, you know. And I figured it really meant the end of my Senate career, which was all I had. I didn't think it would be as bad as it was. But we took them all on. We challenged the ADA Humphrey kind of liberals who were for the war. And after New Hampshire Bobby got in, so we crossed the Kennedys -- and, you know, if you crossed the Kennedys back then, and the Johnson people and the regular Democrats, and the liberals, your lifetime as a Democrat wasn't going to be very good. But we figured we'd do it anyway, and it set us free.

How would the '68 campaign have played out if Robert Kennedy hadn't been killed in California?

I think we would have beaten him in the New York primary. We didn't have enough strength to win [the nomination], but we would have split the vote, and things might have gotten pretty wild and chaotic at the convention. But Bobby coming in when he did changed the whole tenor of the campaign, which had been somewhat respectful of Lyndon. We said, "Look, Lyndon had a good civil rights record; it's the issue of the war and what the war is doing to everything else." But Bobby came in and attacked Lyndon; you know, he talked about Lyndon appealing to the dark impulses of the American soul, that stuff. It sounded familiar -- I think [Kennedy speechwriter Dick] Goodwin had written it for me, and I wouldn't use it. So he gave it to Bobby and Bobby said it.

A number of people fairly close to Kennedy told him not to run against you.

And some who weren't, like [Sen.] Wayne Morse. Wayne wrote Bobby a letter saying don't do it, you'll divide the antiwar forces. Some stayed with me, like John Galbraith. Others deserted -- Arthur Schlesinger. They all had to give reasons; some of them said, "Well, he's not campaigning [hard enough]." But, hell, we beat Lyndon in Wisconsin, Bobby in Oregon, and Humphrey in two or three places where he ran. If you beat the three top Democrats in one campaign, you must be doing something right. They said I wasn't active enough, I didn't attack Lyndon enough. But I had never lost an election until we lost Indiana to Bobby. I'd won about 10 elections in Minnesota for the House and Senate. I used the same methods as I was using in the '68 campaign, and they had worked for 20 years. Polls showed me winning by seven points over Nixon so what did they want me to do? They said, "Well, your campaign's not effective." Well, you know, something was effective. They had no case, but they were always giving excuses -- he doesn't work hard. He doesn't go to factories. We must have gone to every factory in New Hampshire. We missed one, I think -- we went to the wrong place.

Dick Goodwin claims that on election night in the California primary, Bobby knew it was a close vote, and he was afraid you might win in New York and he said to Goodwin, "I think we should tell him [McCarthy] if he withdraws now and supports me, we'll make him secretary of state." Suppose that offer had been put to you -- how would you have responded?

I wouldn't have served in President Bobby Kennedy's Cabinet in any circumstances.

Why not?

I didn't think he was trustworthy. I didn't really think he should have been made attorney general. I thought Jack made three mistakes very early: he shouldn't have appointed [Dean] Rusk [secretary of state], shouldn't have appointed McNamara, and he shouldn't have appointed Bobby. Rusk was with some China lobbying group back in the '50s. McNamara because he was one of those guys from the automobile industry who think they're geniuses, and they can't make mistakes. And with Bobby I didn't think you appoint your campaign manager attorney general. They used to make them postmaster general -- Jim Farley under Roosevelt, you know, and that was all right.

Did Jack appoint Bobby because he wanted someone close watching Hoover and the FBI?

No, I don't think Jack was as worried about Hoover as Bobby was. Jack was pretty cool, you know. I guess he figured he wanted somebody he could trust. I don't know. It was just a bad appointment. Bobby was inexperienced and he was Jack's brother and he was his campaign manager. The attorney general ought to be the most impartial guy you can find.

Why didn't any senior Democrats go to Jack and say, "Look, we're for you but this is too much?"

Jack had kind of captured the presidency. I think when you get the presidency by capturing it, even if it was by virtue of two or three primaries, it's like booty, and from that time on, every guy who wins, wins primaries, says, "I got it myself."

So even then there was no party in the traditional sense.

That's right. And look at the staff people and Cabinet members. Rusk was a foundation guy; he had no record as a Democrat. McNamara had no record as a Democrat. And Bobby bragged about voting for Eisenhower over Stevenson in '56.

If Bobby Kennedy had become president, what kind of president do you think he would have been?

Well, I just don't think he had the restraint.

Dominic Sandbrook, the author of "Eugene McCarthy: The Rise and Fall of Postwar American Liberalism," quotes you as saying after Robert Kennedy's death, "He brought it on himself."

Another distortion. What I said was that Bobby introduced an issue in the campaign. He said he was going to give jets to Israel. Appropriations to Israel had been in the general appropriations; over that amount you had to get congressional approval. I was told that Bobby went around to synagogues in California saying he would give F-15 jets to Israel -- they hadn't asked for them. Sirhan Sirhan read this and said, "I've got to kill him." I said that Bobby was raising an issue that shouldn't have been an issue. It had nothing to do with Vietnam, nothing to do with him and me.

What do you think were Bobby's good qualities?

He was a pretty good prosecutor. He had good lawyers around him. But he was funny, you know. He convicted some bankers in Minneapolis -- big bankers -- and they called me and asked if I could talk to the attorney general about their case. To eliminate unnecessary hurdles, the government had told the banks they could agree on charges for certain services, like overnight deposits, charges for cashing checks or giving apples to people who opened accounts -- not any big items, just nuisance stuff. But later on the government changed the law, and these guys kind of resisted; they said why don't we just go on the way we were, it doesn't make any difference. But it was a violation of the law, and they got them on charges of conspiring.

So I went to see Bobby and said these are responsible people and you don't have to put them in jail. He didn't say anything, but in the '68 campaign he claimed I'd tried to get special treatment for big bankers. At the time I told him these guys can't go to a Mother's Day dinner without conspiring; they're all related to one another. They were bankers, you know, but they were never my supporters. But Bobby kept that and put it in the campaign. It wasn't much. If you're a senator, you go down to the attorney general about something like that and if he tells you I don't think we can do it, you say OK.

After your surprisingly strong showing in the 1968 New Hampshire primary -- which helped drive Johnson out of the race weeks later -- some of his advisors urged Bobby to support you instead of jumping into the race. But Bobby said, "Gene McCarthy is not fit to be president."

He said something like that. His mood was not to let the presidency get away. He thought, Let Lyndon run, let him have it -- win or lose, Lyndon would be gone in '72. And Bobby could come on.

Did you tell him you only wanted one term?

Yeah, but I never said I'd be for him, though. I was very careful. I said one term. That was enough for me because I figured with what I was going to do, I'd have a hard time getting reelected.

You've said that in your California primary debate with Bobby, he appealed to several basic American prejudices. What did you mean?

Well, anti-communism and anti-black feelings were two of the exploitable prejudices. Bobby said I would negotiate with communists to end the Vietnam War, and he would not. Well, if you weren't going to talk to the Chinese, the Russians, the North Vietnamese, who were you going to negotiate with? He was really proposing almost the same thing Lyndon did. He kept saying we can't have unilateral termination of the war. The second one was that I was going to move 10,000 black people into Orange County. (I said they wouldn't go.) He had a kind of privatized, private-sector housing agenda instead of public housing; you know, gilding the ghetto, they called it. In effect, it was a segregationist appeal.

But Jack Kennedy had negotiated with communists and he was against segregation.

The one photograph you have on the wall in your room is a sequence of five shots of you and Jack Kennedy while he was president. What was your relationship with Jack?

Once Jack beat Hubert Humphrey in the primaries in 1960, I was really for Adlai Stevenson. I nominated Adlai, but when Jack got the nomination, I worked harder in the general election campaign, I think, than any other senator. He asked me to campaign with the Stevenson people; I went into 16 states for him, logged 60,000 miles for him where the Convairs and DC-3s flew.

Jack was all right. Even in the primary campaign when he and Humphrey were running, I didn't really say much against him; I talked about agriculture. Jack had voted against the farm bill. It was a bad vote. The New York Times and the Boston Globe were picking at the farm program, saying it cost too much. Still farm income was below parity and Jack was one of the first New England guys to break out of the old kind of New Deal farmer-labor coalition. And it hurt.

The [New York] Times would have these damn editorials. I made a speech saying that Joseph of Egypt was the first secretary of agriculture and if The Times had been covering Joseph and the seven years of storing the grain, they'd have said, "Look, there hasn't been any drought for seven years and, look, there are chicken feathers and pigeon fethers coming out of the bins." And CBS would go down and look at them and say, "The grain is piling up too high -- it's coming out over the bins" -- and say, "See, there are droppings in the bins." Yes, we'd say, there's one bird feather. "Can't you keep them out of here?" they'd say. Well, we could keep them out, but it isn't too bad, you know. Then they'd say, "Stop the farm program because of the droppings in the bins."

That was about my only criticism of Jack -- voting against the farm bill. But Humphrey had some pretty positive credits like the farm program, civil rights and a lot of other things, which were pretty important in Wisconsin. Hubert was much more active than Jack was. So Humphrey was pretty frustrated when he lost Wisconsin. He started talking about the black bag they were using to buy the election. Jack talked to me, and he said, "You tell Hubert if he doesn't stop, we're going to unload on him." I said, "I'm not going to tell him; you tell him." But they did unload. Bobby Kennedy brought Franklin Roosevelt Jr. into West Virginia to talk about Hubert's World War II record, said he was a slacker.

Why did Jack Kennedy run for president so young?

I don't know. It might have been with his illness he said I don't have time. I thought Jack should have become vice president, but once he was nominated I campaigned hard for him.

Once he was president how did you work with him?

As a member of the Senate Finance Committee, I worked for Jack's economic program. He and [economic advisor] Walter Heller had a tax cut that challenged the negative stuff of the conservatives, and the liberals' Keynesian doctrines. And I did one of the principal things he did under the Alliance for Progress. We went down and checked out the Christian Democrats in two countries, Chile and Venezuela, gave them some money and worked with them. Frei was elected president of Chile and Caldera in Venezuela. Jack and I were allies, and I've said before that I think we were at a point where we could have been friends. He had really settled into the presidency when he was killed.

How about Ted Kennedy? Did you get along with him in the Senate?

Oh yeah. I got along with him. Everybody got along with Teddy.

Do you think he's been a good senator?

He's done good work. Sort of traditional stuff like fighting the courts, and basic welfare stuff. He's persistent, you know. Teddy works hard. I never had any evidence that Teddy participated in the stuff against me in Bobby's campaign. Teddy's all right. He's very friendly to me now.

You said after the 9/11 terrorist attacks that America itself is not innocent of terror.

That's right. It doesn't mean we should forgive those guys -- bin Laden and the rest. We shouldn't. But we need to be aware that we terrorized black people for 300 years, for nearly 100 years after the Emancipation. They were still being terrorized when we passed the civil rights legislation in the 1960s. The other effect that was a kind of terror was our buildup of nuclear weapons. When we produced the hydrogen bomb that was a so-called clean bomb -- it killed only living matter -- it didn't destroy trucks and tanks. They said you wouldn't have to rebuild the cities; the bomb only killed people. We're still not doing much about the terror of nuclear weapons.

What would you have done about Saddam Hussein?

We had to make an effort to see that he was stopped, but we didn't have to go to war to do it. We could have set up a task force to capture him -- we did capture him -- without starting essentially a world war. We didn't have to disturb the entire Middle East to do it.

Do you think that John Kerry's record in the Vietnam war and then as a protester after he got out will help him win -- and help the country put Vietnam behind it?

Well, I hope so. I think if you're looking for a guy whose Vietnam record was good, why his was good. He went as far as he could. You can't fault him for it. You can fault McNamara but not Kerry. Then he said, I've done it. I'm going to go home and oppose it. Kerry's kind of like the best of the elite in our society; they have a sense of duty. They can be pretty courageous. Like Jack Kennedy. The nobility ought to help protect the peasants. At least stand up with them if they're going to be in politics.

Anything else you want to say about the 2004 election and politics in the future?

We've got to fight Bush pretty much across the board. Long term I think you've got to be looking for a third party, and if the Democrats can't win this time, then we really have to have one. But this time we've got to beat Bush. And I'll do all I can to help Kerry.

What do you think your legacy will be? How do you want to be remembered?

I don't know about these legacies. I'm against announcing legacies beforehand. I think I established that a president of your own party might be challenged over a war. No Democratic president has started a war since 1968. Republicans haven't learned the lesson, though there are some signs the Republicans may be getting ready to revolt.

Do you still write poetry?

Never say you won't write another poem. Being a poet is a little like being an Episcopal bishop. I've had good associations. I got to know Alan Tate when he was at the University of Minnesota. He had heard me quote Plato, and he showed up at my house, and said, "I'm looking for a poet-politician."

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Editor's note: As the country heads toward another wartime presidential convention, with protests planned in the streets of New York during the GOP gathering in late August, it seems fitting to close this interview with a poem of Eugene McCarthy's, inspired by the police assault on young antiwar demonstrators during the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago. It is reprinted with the permission of Mr. McCarthy.

Grant Park, Chicago

Morning sun on the pale lake,

on plastic helmets, on August

leaves of elm, on grass,

on boys and girls in sleeping bags,

curled in question marks.

Asking

the answer to the question

of the song and of the guitar

to the question of the fountain,

of the bell and the red balloon

to the question of the blue kite

of the flowers and of the girl's

brown hair in the wind.

There are no answers

in this park, said the captain

of the guard.

Then give us our questions

say the boys and girls.

The guitar is smashed,

the tongue gone from the bell,

all kites have fallen, to the ground

or caught in trees

and telephone wires

like St. Andrew, crucified,

hang upside down.

The balloons are broken

flowers faded in the night

fountains have been drained

no hair blows in the wind

no one sings.

Three men in the dawn

with hooks and spears,

three men

in olive drab gathered

all questions into burlap bags

They are gone --

There are no questions

in this park

said the captain

of the guard.

There are only true facts

in this park

said the captain

of the guard.

Helen did not go to Troy.

The Red Sea never parted.

Leander wore water wings.

Roland did not blow his horn.

Leonidas fled the pass.

Robert McNamara reads Kafka

Kirkegaard and Yeats -

and he said on April 20,1966,

"The total number of tanks in Latin America is 974,

This is 60 percent as many as a single country,

Bulgaria has."

There are only true facts

in this park

said the captain

of the guard.

Shares