On Flag Day, June 14, 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed legislation that put the words "under God" into the Pledge of Allegiance. Fifty years to the day later, the U.S. Supreme Court has decided that those words will stay in the pledge -- at least for now, and probably for a very long time to come.

Michael Newdow, the emergency room doctor, law school graduate and lifelong atheist who challenged the invocation of God in the Pledge of Allegiance, knew this day was coming. In an interview with Salon last week, Newdow predicted the Supreme Court would issue its decision today, but he believed the court would see some kind of poetic justice in taking "under God" out of the pledge exactly 50 years after the words went in.

Newdow was right about the high court's timing, but wrong about everything else. He thought the justices might agree with him unanimously. They did just the opposite. Five justices said the court should steer clear of the pledge controversy because of legal questions over Newdow's custody of his 10-year-old daughter; three others said he had standing but was wrong on the merits of the case; and the ninth justice, Antonin Scalia, recused himself after making public comments suggesting he had decided to rule against Newdow even before the case was heard.

While Newdow may someday be able to overcome the ruling that he lacked standing -- he's fighting for equal custody of his daughter, a legal status that might allow him to renew his case -- the long-term outlook is grim. With Scalia and the three concurring justices already aligned against him, there's little chance that this court will ever decide that the invocation of God in the pledge is unconstitutional.

Newdow was crestfallen this morning -- but not so much for his loss in the pledge case as for the commentary it made about his rights as a parent. "I may be the best father in the world," Newdow told the Associated Press minutes after the ruling came down. Newdow's daughter spends 10 days a month with him, and he's fighting hard for more. "The suggestion that I don't have sufficient custody [to satisfy the court's standing requirement] is just incredible. This is such a blow for parental rights."

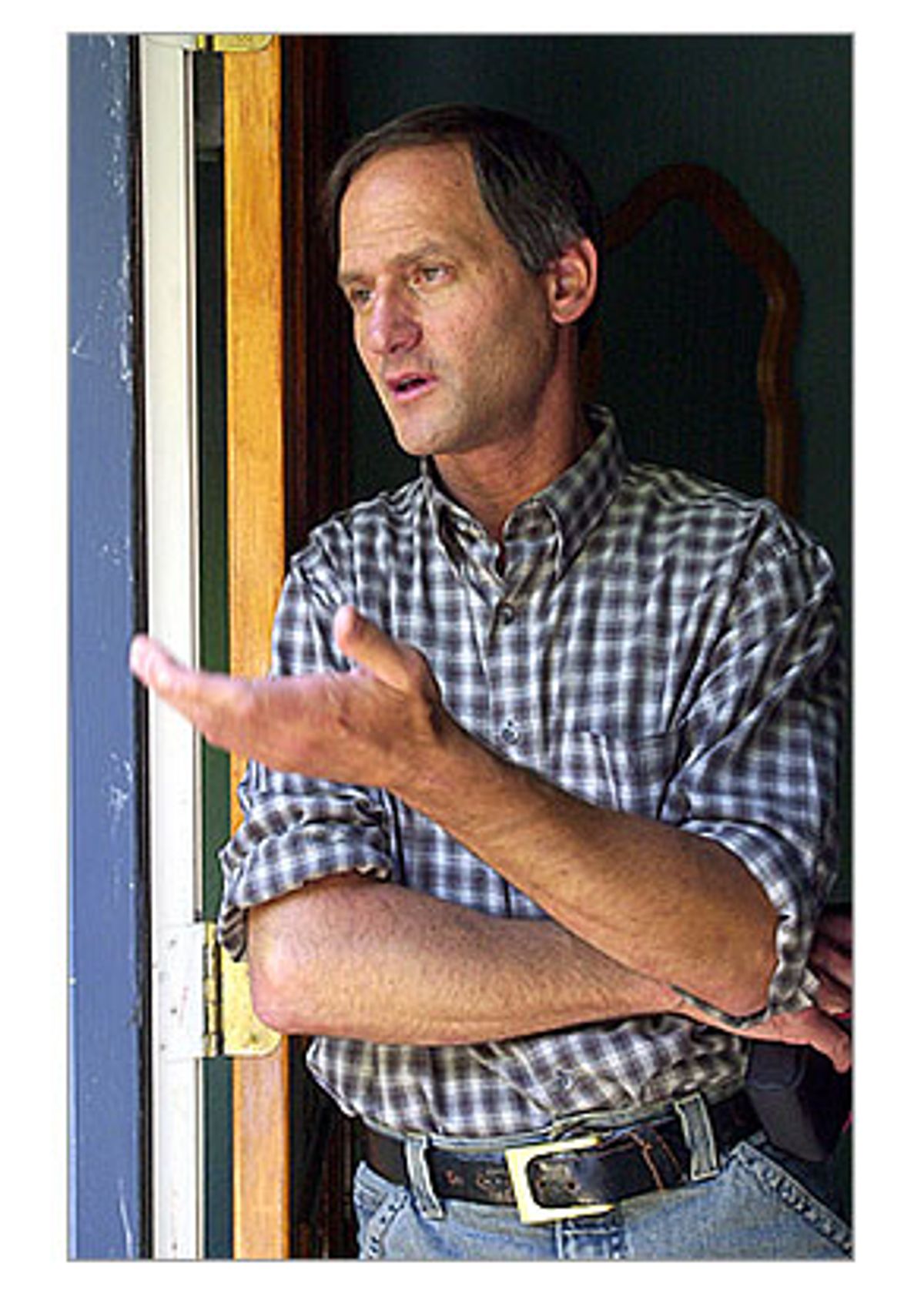

Newdow's focus on the family-law aspect of his case might come as surprise to those who -- like the angry Christian patriots calling for his death at the slam site www.michaelnewdow.com view him as a single-minded zealot working to write God out of public life. But to those who know him, Newdow's reaction was to be expected. Rambling around his suburban Sacramento home last week, Newdow said the pledge case, which had not yet been decided, was already "old news." Each time he started to discuss it, the conversation shifted somehow to Newdow's fight for equal custody of his daughter. He's obsessed with it, consumed by it, and he can't not talk about it -- even if what he says is unhelpful, embarrassing or beyond impolitic.

The family law judges are "idiots," Newdow said last week, and the mother of his child is an "abuser" who tricked him into fatherhood in order to get his money.

"I won't get into the details," he said, but then he did, describing the day a decade ago when his ex-girlfriend got pregnant. "We were out camping, we were both naked, and I said: 'No, I don't want to. No, I don't want to,'" Newdow said. "The fact is, she knew that from the beginning, and I think she planned it, and I think that if I wasn't making 10 times as much money as she was, there's no way she ever would have had this kid."

A few minutes passed, and Newdow tried to rein himself in and make nice about the mother of his child. "She's a lovely person," he said. "She's very sweet, she's completely nonthreatening, she's lovely." But Newdow couldn't stop there; he kept going, and in the process ended up comparing her to a notorious California killer. "She's a nice person, she's friendly," he said. "But so is Cary Stayner."

The lawyers representing Newdow's former girlfriend in their custody dispute did not return calls for comment.

Newdow's rants may make it hard to like him -- don't get him started on how abortion rights give women an unfair advantage over men when it comes to handling unwanted pregnancies -- but they also make his journey to the Supreme Court all the more impressive. For four years, Newdow methodically litigated a constitutional challenge that virtually no one took seriously. An atheist jokingly ordained as a mail-order priest, Newdow contended that, by inserting the words "under God" into the pledge in 1954, and by requiring the teachers in his daughter's classrooms to lead the pledge each morning, Congress, the state of California and his daughter's school district violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.

In 2002, Newdow won a major -- but ultimately temporary -- victory: Two of three judges on a Ninth Circuit panel agreed that the school district's policy violated the First Amendment.

The decision was condemned in God-fearing, bipartisan lockstep. The White House declared it "ridiculous," the Senate voted 99-0 in favor of a resolution of "support" for the pledge as written, and Antonin Scalia opined, in a speech to the Knights of Columbus on "Religious Freedom Day," that, while Congress was certainly free to remove the words "under God" from the pledge if it wished to do so -- and it plainly did not -- no court could make the change by "judicial fiat."

When the Supreme Court agreed to take the case, without Scalia, who recused himself upon Newdow's request, Newdow insisted on arguing it himself. And this March, he delivered what the New York Times called a "spellbinding" performance. For a half an hour of oral argument, Newdow was calm and in control, holding back his lesser angels just long enough to argue his case better than anyone else could have.

"I'd hate to have a lot of Newdow wannabes argue their own cases, because they're almost always a disaster," said Richard Lazarus, a former assistant to the solicitor general, who runs Georgetown University's Supreme Court Institute. "But for 30 minutes -- 30 minutes, not 31 -- Newdow very effectively put himself on check."

Newdow's performance came as a surprise to many lawyers and probably to the justices as well. Chief Justice William Rehnquist tried to trip up Newdow by forcing him to admit that that the congressional vote to add "under God" to the pledge in 1954 had been unanimous. When Rehnquist said that a unanimous vote didn't sound very "divisive" to him, Newdow countered by saying that an atheist could never be elected to Congress, underscoring his point that seemingly innocuous religious recitations like "under God" can marginalize and exclude nonbelieving minorities.

The normally silent Supreme Court gallery broke into applause, and a fuming Rehnquist threatened to clear the courtroom. After the argument, several justices reportedly joked among themselves: Was the applause coming from atheists who supported Newdow or from Christians who were cheering the idea that an atheist could never be elected to Congress?

Outside the courtroom, Solicitor General Ted Olson, who argued against Newdow on behalf of the Bush administration, and former Independent Counsel Ken Starr, who represented Newdow's ex-girlfriend, were both effusive in their amazed praise of Newdow's presentation.

Lawyers who know Newdow better were even more surprised.

Tom Goldstein, an experienced Supreme Court lawyer whose firm publishes the essential SCOTUSblog, talked with Newdow often about the pledge case in the months before the oral argument. Lawyers like to say that a man who represents himself has a fool for a client. Goldstein saw some of that in Newdow, at least before the oral argument began. "He's so passionate about the family law stuff," Goldstein said. "He's over the moon about it, and he admits it."

What he doesn't do is control it. In one family law proceeding, Newdow equated the intercourse that led to the conception of his daughter to "date rape." In a conversation last week, he spoke passionately of the injustice he sees when a man happens to impregnate a promiscuous woman. If a woman "sleeps with 57 men, that's never the issue," he says. "But the fact that [one man's] sperm cell happened to fertilize the egg and [another] guy's didn't? He's guilty and the other guy isn't. It's stupid. Neither of them intended to have a child. It was just sex."

Public statements like the "date rape" comment "couldn't be less helpful or more counterproductive" to Newdow's cause, Goldstein said. "But it's how he feels, and there isn't a screen between his emotions and his mouth when it comes to the wrong he's convinced the family law system has committed."

Goldstein feared Newdow's emotions about family law would spill over into his presentation before the justices. He had an opening for it; as Monday's ruling showed, the court saw questions about Newdow's custodial rights as a path to avoid ruling on the substance of his case. "I had talked with him beforehand, and I thought he was going to argue the case [in the same way that] he feels about the case," Goldstein said. "He needed to improve a lot, but he was very willing to listen, and he was unbelievably prepared. It's fair to say he's a brilliant guy ... But like all of us, he's a little blinded by his faith in his position."

But Goldstein said that Newdow understood what he needed to do -- both stylistically and substantively -- by the time he appeared before the eight remaining justices. In oral argument, he was careful not to argue for too much; rather than arguing that the Supreme Court ought to strip its Establishment Clause jurisprudence back to "make no law" simplicity, he argued that the "under God" language in the pledge is different -- that its genesis was more distinctly religious, that its effect is more coercive -- than other invocations of God in public life.

"What Michael Newdow did very effectively, other than being a smart guy, is that he was willing to develop the best possible argument to try to win in the court," said Georgetown's Lazarus. "The hardest thing for people to do when they represent themselves is that they think that, when the justices ask them a question, they're being asked to testify as to what their views are. And that's not true. What good lawyers do is come up with the best possible argument they can in a case. That's what Newdow did, and it was very impressive. He was willing to ask for less than what might be his ultimate aim."

In the end, of course, it wasn't enough. With the current makeup of the court -- and the outcry that would come if "God" were stricken from the pledge -- the case was probably unwinnable, no matter who argued it. As Goldstein explained, "What [Newdow] was not able to do -- and I don't know that anybody could do -- was deal with this court's sense of, 'Oh, give us a break. We've been doing this a while, and it doesn't cause a real problem, and if we rule for you, the country is going to go apeshit.'"

The Rev. Barry Lynn, executive director of Americans United for Separation of Church and State, acknowledged last week that the deck was stacked against Newdow, that the court wasn't likely to consider his challenge important enough to warrant the controversy that a decision in his favor would cause. "But it is that important," said Lynn, whose group filed an amicus brief in the case. "It's a question of whether we have two classes of people who love their country: one who is the approved kind -- you believe in God and you love your country -- and everyone else, the people who love their country but don't want to take a religious oath every time they say so."

Lynn said Monday he was "disappointed," but he took some comfort from the fact that a majority of the justices decided the case on technical grounds and left the substantive question for another day. "This means that there will be other parents with custody lining up to bring the same kind of suit in California, hoping that it will be on the same trajectory as Michael's." Lynn said he was particularly encouraged by Justice Anthony Kennedy's silence. "The fact that Justice Kennedy did not write a decision in which he opined on the merits suggests that he's still open-minded," Lynn said, leaving open the possibility, at least, that five justices might ultimately agree with Newdow if they were forced to deal with the substance of his case.

Last week, Newdow seemed to find it inconceivable that the justices would avoid the constitutional issue his case presents -- that they wouldn't see, like him, that this is actually an "easy case" under the First Amendment. The Establishment Clause says Congress shall "make no law" respecting the establishment of religion. Under any test the Supreme Court has articulated, Newdow said, the inclusion of "under God" in the pledge and the requirement that teachers lead the pledge in classrooms amount to just such a law. Pounding on his kitchen table, his voice rising sharply, he said: "Two plus two equals four. I understand that a lot of people are going to keep going, 'Two plus two equals five.' But it's four! Look! We can count it out here."

Asked what would happen if he were to lose the case, Newdow grew quiet, like a Christian whose faith in God has suddenly been called into serious question. He looked off into the distance, and his fingers worried the edge of the kitchen table. He started a sentence then stopped. As he contemplated the possibility that eight justices might not see his truth, the guy with all the answers and opinions was suddenly inarticulate.

"If I lose this one, then there's no reason to bring another Establishment Clause case because I'll know that they're clearly ... I can't win ... this one is just so clear, you know?" He started to say something about his "faith," but he never finished the thought.

And then the doubt began to lift -- he could see it so clearly again -- and Newdow found his voice. "You know, we had a pledge for 62 years and it worked fine, and then they took these two words -- "under God" -- and they stuck them in there, and ... it violates every single test the Supreme Court has ever set out."

If the justices don't see that, it doesn't mean Newdow was wrong; it just means he'll have to wait. If he lost, Newdow said last week, he would just have to think of his case as another Plessy vs. Ferguson, the 1896 Supreme Court decision that allowed "separate but equal" facilities for African-Americans until 1954, when the Supreme Court decided Brown vs. Board of Education. "I still think I'll win eventually," Newdow said with a confidence that Homer Plessy probably never had. "It may be 50 years down the road, but I'll win eventually."

Shares