I saw a quote the other day from the English poet Stephen Spender. When he first gave up men for women he remarked that being with a woman is "more satisfactory, more terrible, more disgusting, and, in fact, more everything" than being with a man.

It made me think. I was lucky enough to be with a woman for many years in between being with men, and I don't think the libido is all that discriminating -- I don't think the gender of the person with whom you exercise your sexual identity is crucial. We'd make groundhogs into sex objects if they were all there were. But what is important is that deep, sexual identity that the young put together in excitement and anxiety from what opportunities come their way. A heroic achievement, though -- like learning to talk -- and no one ever congratulates you.

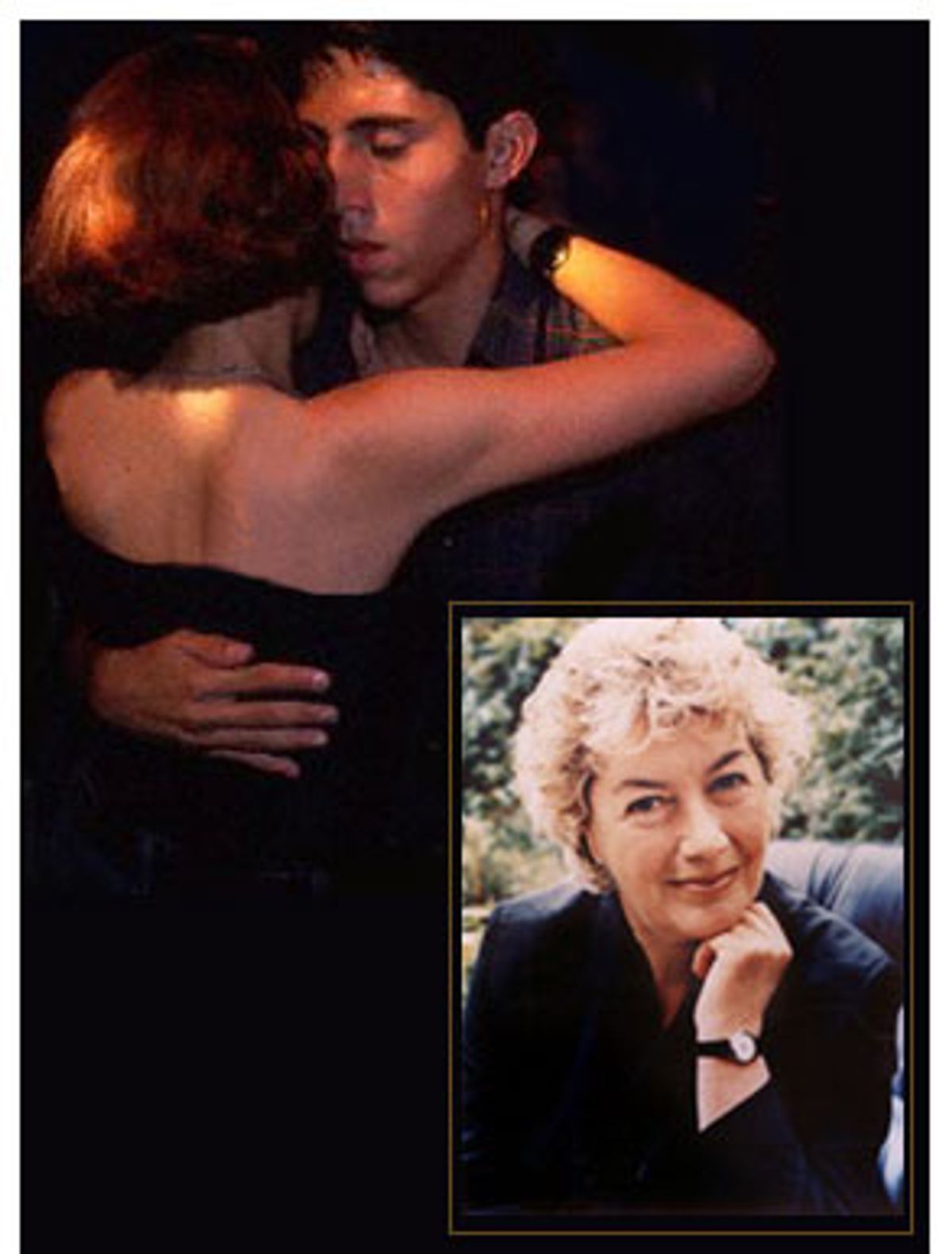

The time and place in which I believe that my sexual identity was formed is the most memorable of the sexual phases of my life. It wasn't the most thrilling time; the thrills come from love. It wasn't the most precious; the most precious is now. But it was the most intense in that it was the only time that sex, generalized, was more important to me than the people I had sex with.

I was 13 years old and living in a small town in Ireland when something happened within me and I began to be buffetted by sexual feelings like a person going over Niagara Falls in a barrel. I didn't know that this was a thing called puberty. Information was very tightly controlled in those grim days before the mass media got under the skin of the patriarchy, and if I couldn't find something out in a book I couldn't find it at all. But there was nothing much about our bodies except them being Temples of the Holy Spirit in print in Catholic Ireland in the 1950s. Most words to do with the body were dirty, never mind the bodies themselves. I'd been ashamed to tell anyone, some time earlier, when my periods started. Mothers themselves were tongue-tied. As for Irish fathers -- gimme a break.

We lived in a big house in a small, gray town, and because the house was rotting my mother could not make it fast against my breaking out to go down to the Town Hall to the dances. That's what I thought I would die if I did not get to: the dances. The word sex simply didn't come into my head. I hardly knew it, and I'd never heard it said. The thing that happened between people that babies came from was not called sex in Ireland in the 1950s. Nothing was called anything. (By the way, everywhere has its Irelands, and every place has had a 1950s one time or another; you can't write this off as anthropology.)

The dances started at 10 p.m. and they ended at 4 a.m. They were the only thing in the miserable country that had anything of youth and sweetness -- not that "sweetness" was the word that sprang to mind as midnight approached and the bone-weary band in greasy blazers ground out "I Believe for Every Drop of Rain that Falls" to the rows of girls sitting stiffly around the edge of the floor on wooden chairs while the fellows trickled in, red-faced, cigarettes cupped in their stained palms, from the pub. They waited for the critical mass of maleness to accumulate, which would empower them to sidle across to a girl and slide her onto the powdered floor. Not a word was spoken after the initial mumble of invitation, of course, except sometimes when the couple broke apart for respectability's sake in the interval between tunes in the three-tune sets. "Did I see you here before?" "Is that your friend you're with?"

Slow waltzes were the killers. A big, red, wet hand slammed onto your fanny, pushing your gingham-frocked loins in against the toilet-roll-like thing (referred to between girlfriends in the utmost privacy as his "er") that throbbed in his trousers. "Vaya Con Dios" the plump crooner in an auburn wig intoned and both dancers murmured the words, looking fixedly past each others' ears, and after a while the fella would throw the other gorilla arm around the girl's shoulders in the hope of squashing her chest against his shirt. But many a girl had stuffed hankies into the pointy cups of the bras of the time and held back from the upper-body embrace, for fear of discovery. We didn't know about transvestites then, and that lots of guys prefer a mineral pair of breasts to fleshy ones.

Transvestites? Are you kidding? We'd never heard of orgasms. Well -- I hadn't. I was a pupil at a convent school, and although I was a keen reader, if there were orgasms in any books I read, I hadn't noticed them. I once asked my mother what the line in an American book meant that said, "What she needs is a roll in the hay" and my mother grabbed the book and gave me a terrible glare. Wordlessly.

Don't think there was anything funny about the dance halls of the poor in a viciously repressive society. If any of the old men who ran the country had ever visited them, and if they'd had hearts, they would have wept. I can report on them only because I was a refugee from the middle class, driven down the social scale by my hormones. I see now that young working-class people endured life without jobs, in the few years they stayed in Ireland before they emigrated, because they had this. This thick excitement. The tiny concrete Ladies with its two disinfectant-smelling stalls filled during the night with girls with gleaming eyes, climbing over each other in front of the one small mirror to spit on their mascara and sweep their lashes, smack scarlet lipstick onto their lips, slick the kisscurls on their cheeks, rub Vaseline into their eyelids. Then they tippytoed out again on their high heels to be mashed against whatever man would dare the publicity of crossing the floor to claim them. The buttons on their stockings' suspenders, the buckles on their waspy belts, the metal strap-adjusters of their bras left their impressions on him, and his -- his nameless thing -- left a hot memory in the hollow where her thighs met. Down There, as close girlfriends might call it in a whisper.

Those were the days when male and female danced close. Don't ask me why the priests and the other old men went berserk and tried to ban jive and then rock 'n roll and then the twist. Fast dancing is relatively asexual. It's slow dancing done late at night by people both innocent and ripe that brings meltdown. Those dances were the most exquisite, prolonged foreplay the world has ever known, even though all they led to was more foreplay.

Later, much later, when there was a visible miasma of sweat hanging over the shambling scene, the fella you wanted might say "Are you going home with your friend?" -- the fellas were afraid, you see, to lay an "I" on the line, as in the sentence, "Can I leave you home?" And if, while the band was playing "Goodnight Sweetheart See You in the Morning" you said no, you weren't going home with your friend, he'd say "See ya outside."

When the National Anthem began, he'd slip away to stand with the fellas -- so as not to be seen standing beside you -- and outside he'd come out of the dark and put his arm around you and lead you away to commit intimacies.

The little town might have been designed to hide the 70 or 80 couples -- hot, feet smelling, hair awry -- in that time before dawn, in doorways, alleys, the driveways of the respectable, under the railway viaduct at the harbour, on the broken benches along the path above the silent sea. Nobody lay down, and not just because in Ireland the grass is always damp. It would have been too dangerous. It would have amounted to a confession. Courting was a business of fully clothed body straining to touch at every point another clothed body, like a dance-hold but without the poor old band thumping out "Don't Let the Stars Get in Your Eyes." There was no movement in any direction except forward, ever forward. Kisses were like squid turning inside out. And the hands of the fella crept and re-crept up the nyloned thigh to the suspender and then onto the silky flesh above the suspender -- maybe once or twice flicking by accident the cotton of the panties. There. Where? You know -- there!

I don't know how we survived. I don't know how back then so many of us managed not to "go all the way" -- the phrase in use between very close girlfriends for having sex. Fear must work. God knows what phrase the fellas used. They all said fuck all the time but not as a verb. Between themselves they said it -- you'd overhear them -- they never said anything to us. I see in America that anything less than perfection entitles the locals to consider themselves sexual invalids and to spend thousands of dollars on therapy for their malfunction. Boy, they should have gone through what we went through! Fellas, particularly. Our brave boys had to survive hour on panting hour of not getting there. Even between layers of clothing they weren't allowed to move up and down against the girl. Somehow we knew that was wrong. Don't ask me who makes the rules. They must have had "ers" like pretzels.

As far as I can see my generation survived its surreal introduction to the life of the senses. It so happens that life has sent me back in recent times to that small town -- I visit a senior citizen there from time to time. When I saw that they were about to demolish the Town Hall I went in there, and I stood in the dimness on the pitted wooden floor and ran my fingers over the stippled paint on the concrete pillars we used to lean against, fake-nonchalant, and when I pushed open the door the same old pungent disinfectant wafted from the Ladies Toilet. The place was so small, and so primitive; I could hardly believe the Wagnerian quantities of hope and disappointment and desire and excitement it once contained. And humiliation. I, for example, was humiliated for a long time. I often limped on sore feet back up the street to the house we lived in to haul myself in through the window with the last of my energy. I was just growing into my body and beginning to be sure of having a boy "leave me home" when the establishment came down on me like a ton of bricks. The nuns, my father, the local police -- you name it, it came down on me. Hey presto, I was off to an Irish-speaking boarding school in a region of conifers and gray lakes, up near Northern Ireland, and so as to fit in, for the next few years I went back to having no body.

In that town I see youthful grannies and their blonded daughters collecting kids from school and talking as they lean on trolleys in the supermarket and standing in the street calling across to friends and laughing. Like myself, they seem perfectly normal. But of course I'm not sure what normal is. Do we, who were forced to become connoisseurs of real physical bliss but bliss forever interruptus, have a different sexual identity than people who had a rational, hygienic, friendly introduction to sex? People who brought their girlfriends and boyfriends back to their parents' house? People -- as I always think of them -- in gray cotton underwear and perfectly toned bodies? Are we secret aristocrats? Or are we the pathetic victims of a puritan church and state? I don't know how you'd set up a controlled experiment to find out. I'll never know.

What I do know is that my formation left me wordless. To this day I don't have a vocabulary for All That. I have to hide my shock at the things other people say. Penis -- things like that. We'd have killed ourselves first. When I read sex-advice pieces they always say, "Tell him! Tell him what you want and encourage him to tell you what he wants!" But leaving aside the erotic flaw in this, which is that there isn't anything anyone wants if the other person doesn't want anything, how can you have an illuminating chat if you don't know how to say it? If Down There is as precise as you are happy to be? If you call his "er" "your 'er'" and your own "er" "my 'er'" and at that, blush in the dark at your explicitness? I don't know whether to be proud that words had such meaning in the culture I came from. Or to accept that there must be a curious condition where part of the frontal lobe is burnt out by lust.

Shares