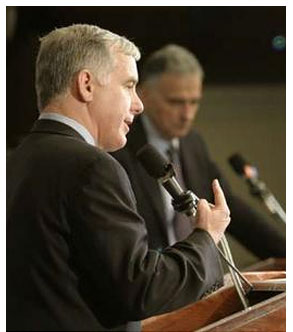

Howard Dean wasted little time getting to the point in a debate with third-party presidential candidate Ralph Nader on Friday. After listening to Nader’s standard posturing about how only he can save the Democratic Party and the nation from the “corporate interests” that have consumed politics and government, the former Vermont governor struck hard: “Ralph, I think you’re being disingenuous about your candidacy this year.”

In his rapid-fire delivery, the onetime Democratic presidential front-runner rattled off all the ways he saw Nader as a hypocrite: Nearly half the signatures Nader gathered in a failed attempt to get on the Arizona ballot were from Republicans. A significant amount of his campaign kitty comes from Bush-Cheney donors. And, said Dean, “you accepted the support of a right-wing, fanatic Republican group that is antigay in order to help you get on the ballot in Oregon” — a reference to the Oregon Family Council, which produces a “Christian Voter Guide” and campaigns against gay marriage.

“This is not going to help the progressive cause in America,” Dean continued. “The thing that upsets me so much about this is, you have the right to … get in bed with whoever you want to, but don’t call the Democratic Party full of corporate interests. They have their problems, we all have ours, none of us are pure. And this campaign of yours is far from pure.”

Dean’s riff was greeted with gleeful applause, and Nader appeared momentarily shaken by its ferocity. Dean insisted, “My purpose here is not to smear Ralph Nader,” which prompted Nader to respond sarcastically, “Oh, no. Not at all!”

Because the debate was sponsored by the scrupulously evenhanded National Public Radio, the room at the National Press Club was filled with equal numbers of the opposing camps. The Nader section tried to pump some wind back into their guy, squealing with laughter at his teenager-like rejoinder. Dean plowed through their applause. “I urge you not to turn your back on your own legacy,” he pleaded to the consumer advocate.

The exchange took place against a backdrop of polls showing that Nader may play the spoiler for Democrats again this year as he did in 2000, when he siphoned votes in key states from presidential candidate Al Gore and helped put George W. Bush in the White House. But now, having provoked hostility from many Democrats with his quixotic but damaging third-party run in 2000, Nader is having trouble finding a third party to call his own. Last month, he was rejected at the convention of the Green Party under whose banner he ran in 2000. He’s straining to get on state ballots via minor third parties, including the rump of the Reform Party, founded by Ross Perot and last used as a vehicle by far-right-winger Pat Buchanan in 2000. Nader recently pulled out of Arizona after a group of voters backed by the state Democratic Party challenged the validity of signatures he had collected to gain ballot access.

Yet Nader appeared unbowed in the debate. He was alternately charming and strident, returning again and again to his theme that American politics is a puppet pulled by the strings of corporate America. While most progressives would cite the invasion under false pretenses of Iraq as the major issue of the campaign, Nader said it was “the domination of our country by a concentration of greed and power in the hands of multinational corporations who have no allegiance to our country other than to control it or abandon it as they see fit.” Almost as an afterthought, he slammed John Kerry and his running mate, Sen. John Edwards of North Carolina, for voting for the congressional resolution to authorize the war in Iraq, and accused Dean, who opposed the war, of abandoning his principles by his support of the Democratic ticket. Nader also called for a pullout of American troops from Iraq. But he kept returning to his basic theme that the Democrats can accomplish nothing but betrayal: “If you really want to do something about poverty and the criminal justice system and the failed war on drugs, how can all that fit inside a Democratic Party that has ignored, year after year, changes for a more just and prosperous America?”

Dean parried effectively, with the directness that helped win him a fervent following during the primaries, before he crumpled after his third-place finish in the Iowa caucuses. “I’d grant you that there is significant corporate influence that we don’t like,” he said, and pointed out that Nader should not let the “perfect be the enemy of the good.”

Dean continued: “I’m not running for president right now, not just because I lost in Iowa, but [because] I made the calculation that if I did, I would take away votes that would otherwise go to John Kerry and result in the reelection of George Bush. That is a national emergency, and we cannot have it. My argument simply is, When the house is on fire, it’s not the time to fix the furniture.”

Nader assailed the two-party system, asserting that it stifled new debate, and accused the Democratic Party of trying to thwart him. He got an assist from a surprise guest — John Anderson, who ran as an independent in 1980, and asked a question from the audience about whether third-party candidates should be allowed to participate in general-election debates between the Republican and Democratic nominees. Nader said it “ought to be enough” if a majority of Americans say in polls that they want a third-party candidate to debate. “There is no other way to reach tens of millions of Americans other than to go through the gateway of the two parties,” Nader said. But Dean, noting the frustrations of debating in the Democratic primaries with nine other candidates, said he endorsed some limits.

Moderator Margo Adler, host of NPR’s “Talking Justice” program, asked Nader why he didn’t simply run in the Democratic primary, if exposure to his ideas was his goal. “It’s called freedom,” Nader said. “Freedom of conscience, to authentically communicate the necessities to the American people without the trappings of special-interest commercial cash.” Adler asked Dean if the Democratic Party, in opposing Nader’s bid, is showing hostility to third parties. “Not to my knowledge,” Dean said.

But the most entertaining — and revealing — moments came during Dean’s repeated hammering of Nader for the perceived compromises he was making to maintain his precarious candidacy. Again, he returned to the issue of Nader’s support in Oregon from Republican-leaning religious conservative groups.

“It is true,” said Dean, “that the Oregon Family Council, which is a virulently antigay right-wing group, called up all their folks and tried to get them to go to the Oregon convention to sign your petition. I don’t think that’s the way to change the party … The way to change this country is not to get into bed with right-wing antigay groups to try to get yourself on the ballot. That can’t work.”

Nader’s response was to smear Dean as guilty of smearing. “You know what a legitimate smear is, Howard? It’s a smear, premeditated and known. We don’t even know this group. Don’t try and tar us with this.” Dean urged Nader to simply renounce the Oregon group.

“I’ll renounce them,” Nader said, quickly shifting the focus of the debate. “Do you renounce Pfizer and Chevron and other companies who were criminally convicted of crimes by the federal government for giving millions of dollars in the year 2000 to the Democratic Party?”

Dean replied that the need to institute public financing of political campaigns is one reason he ran for president and another reason for progressives to support Kerry. “It’s not going to happen under George Bush.” Then, thrusting again at Nader’s soft underbelly, Dean asked him to return the money his campaign had received from Richard Egan, a Bush fundraiser from Massachusetts who served as Bush’s ambassador to Ireland.

“I wasn’t aware he was a corporate criminal,” Nader said in defense of Egan. “He’s an American citizen. He might be a Republican, but he just happens to believe in civil liberties, maybe. I don’t even know the man. But Republicans are human beings, too.” At this, Nader’s supporters applauded vigorously, a moment that crystallized how unmoored from principle the consumer advocate’s movement has become.

Harping again on how unfair the election process is, Nader stumped for a referendum-style voting system where people could trigger new elections by choosing “none of the above” at the polls. Dean dismissed the idea as another of Nader’s turnabouts. “Can you imagine what would have happened in Arkansas if you’d tried to do civil rights by referendum?” he said.

In a refreshingly energetic debate, the two iconoclasts found themselves reverting to politician-speak at the end, when the moderator, Adler, posed what she called her “favorite question”: If diversity in ideas and perspectives is the main recommendation for a strong third-party system, what did the two have to say about the hurdles to women or atheists running for president? “This country is alive and well if they have candidates who stand up” for their principles, Dean said blandly. Nader, in a non sequitur, advocated repeal of the antilabor Taft-Hartley Act, enacted in 1947. (Not a single union has endorsed him.)

“I still haven’t heard about women and atheists,” Adler chided. The fight was over.

Since losing the Democratic nomination, Dean has campaigned as a stalwart for Kerry and created his own activist organization, Democracy for America. He has taken on the mission of protecting from Nader the flock he has shepherded. Unable to offer cogent responses to Dean’s charges, Nader frantically roams the countryside demanding his relevance.