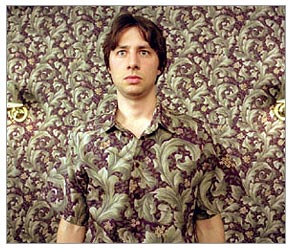

Zach Braff’s “Garden State” may not be the most confident debut picture: It moves forward, pokily at times, with the tentativeness of an injured spider, and in oddly sloping directions. But there’s a moseying delicacy about it that sometimes catches you off-guard: For a first time out (Braff also stars in the picture, and he wrote the script), “Garden State” is for the most part surprisingly unself-conscious. You have to be ambitious to direct yourself in the first movie you’ve ever directed, especially one you’ve written yourself. But Braff (best known from TV’s “Scrubs”) never comes off as a blowhard — not even a fashionably self-effacing blowhard. His motivation feels genuine, as if he wanted to make a movie because he actually had something to say, instead of just wanting to smear his name around as a career move.

Braff plays Andrew Largeman, a floundering actor in his mid-20s who returns to his small-town New Jersey home from Los Angeles for his mother’s funeral. His old pals (all of whom call him by his last name) cluster around: They’re glad to see him, and while they’re fully aware that he’s forsaken them for a grander, more exciting life elsewhere (their class differences are apparent from the start), they draw him back into their ragtag fold without hesitation, almost as if he never left. There’s an extremely bright yet wholly clueless lad who made a fortune by selling his big invention (silent Vel-cro) and now rattles around in a garish mansion. And then there’s Mark (Peter Sarsgaard, in a lucid, nicely controlled performance), who digs graves for a living and makes a little extra money on the side from an activity that’s creepy, illegal and unequivocally disrespectful of the dead.

Largeman follows wherever his friends lead, partly because it’s simply what he’s used to doing: His father, Gideon (Ian Holm), is a psychiatrist who, in a misguided effort to keep his son happy and well-balanced, has caused him to be overmedicated on antidepressants for most of his life. We also learn that many years before her death, Largeman’s mother suffered a tragedy that permanently altered the family dynamic. Largeman creeps through his life in a numbed-out haze: He’s so even, he barely exists.

All of that changes when he meets the precocious oddball Sam (Natalie Portman), the kind of girl whose Grecian-statue beauty at first feels completely at odds with the way her sentences tumble out of her like a clatter of marbles making their way down a vertical maze. But once you adjust to her rhythms, her quirks become lush and seductive: They’re like a length of silk you’d like to wrap yourself in. Portman is vibrant and lovely here. Her performance is relaxed and giddy, but there’s also an edge of sorrow to it. When she’s at her best, as she is here, she’s the kind of actress whose soul seems to shine through her skin.

Braff isn’t quite her match. His pillowy lips and quizzical eyes suggest intelligent sensuality, but in this role, that sensuality is so deeply submerged that it can’t get any air. Braff’s Largeman is just too recessive: While it’s easy to see why he’d choose to play this overmedicated character as a stiffly likable blank, he can’t pull off the harder task of making us see the person behind that blank — the windows are stuck shut and he doesn’t know how to open them.

But to his credit, he doesn’t overdo the lost-boy routine, either: Largeman’s confusion is vaporous but real — Braff doesn’t make the mistake of using it as a club. “Garden State” stumbles here and there: When Largeman has the final showdown with his father, it feels like a manufactured resolution — more a writer’s conceit than a believable moment. The bigger problem is that we never get a sense of Holm’s character to begin with. He’s a sad, spectral man who drifts by in just a few scenes, which is probably precisely the point (he was obviously never much of a presence for his son). Still, as outsiders in the audience, we need a few more clues to hang onto.

The movie also makes Largeman’s transformation a bit too facile — Braff gives himself one of those unfortunate “gulping water in a rainstorm” scenes that have historically been used to signal a character’s sudden recognition that life is worth living to the fullest. (Rain is great, but to some of us, an umbrella and a good blow-dryer are almost religious totems.)

But Braff does capture the sense of coming home to a place you once loved, and realizing, in spite of any lingering fondness you may have for it, that it’s no longer the place for you. “Garden State” is infused with a sense of affection for the suburbs. (In that sense, it bears a resemblance to Eric Mendelsohn’s glowingly understated “Judy Berlin.”) Barely hours after Largeman has buried his mother, he turns up at a friend’s party and sits immovably on a tacky couch while a mini-orgy takes place around him. Braff shows us the scene in sped-up action, with Largeman at the center of it, a placid, zonked-out Buddha, too spiritless to be interested even in sex. Later, when he meets Sam, it seems to take forever for him to give off any even remotely erotic vibes. But by the end, he manages it. Braff, and “Garden State,” give it the old college try, and at least some, if not all, of the sparks catch. Even if the movie doesn’t quite take off, it doesn’t leave you feeling stranded, either.