“The Magic Pudding” is the funniest children’s book ever written. I’ve been laughing at it for 50 years, and when I read it again this morning, I laughed just as much as I ever did. There’s no point in trying to explain why it’s funny. If there’s anyone so bereft of humor that they can read these words and look at these pictures without laughing, then heaven help them, because they’re beyond the reach of advice, instruction or despair.

But we can say something about the language. The book was written nearly a hundred years ago, but you wouldn’t know it; it’s so fresh and lively that it might have been written yesterday. Those of us who love the story, when we meet another fan, are happy to spend a long time exchanging our favorite sentences, quoting them from memory. And there’s something about Norman Lindsay’s muscular, vivid prose that makes it very easy to remember:

“Sam Sawnoff’s feet were sitting down and his body was standing up, because his feet were so short and his body so long that he had to do both together.”

Sam is a penguin. How else would a penguin sit down?

Or this, from Uncle Wattleberry, in a fury:

“‘Nothing short of felling you to the earth with an umbrella could possibly atone for the outrage … My feelings are such that nothing but bounding and plunging can relieve them.'”

Or this little exchange:

“‘The trouble is,’ said Bill, ‘that this is a very secret, crafty Puddin’, an’ if you wasn’t up to his games he’d be askin’ you to look at a spider an’ then run away while your back is turned.’

“‘That’s right,’ said the Puddin’, gloomily. ‘Take a Puddin’s character away. Don’t mind his feelings.’ ‘We don’t mind your feelin’s, Albert,’ said Bill. ‘What we minds is your treacherous ‘abits.'”

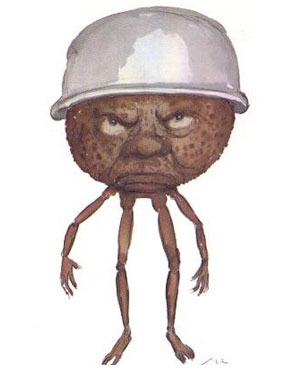

And then there are the pictures. This is one of the great illustrated books of all time. Look at the way Lindsay draws the Puddin’, for a start: his long, spidery-thin arms and legs, his cunning, malevolent expression, the china basin upturned like a hat. Look at the vivid character Lindsay manages to put into every line of the Kookaburra, that low larrikin who exchanges insults with Bill, but gets away with it, because it’s Bill’s rule through life never to fight people with beaks. And there’s one other little detail I love, and which shows Lindsay’s mastery of the traditional disciplines of anatomy and composition. When a character is pointing at something in denunciation, or shaking a fist, or offering a hand in friendship, look at what his other hand is doing: as often as not, it’s held in an energetic fist behind him, at the end of a tensely angled arm, so the figure is perfectly balanced. Every muscle is working: Every line is working. For example, look at the way the Puddin’s arms match Bill’s exactly, in the picture showing the aftereffects of Sam’s attempt at breakfast humor.

And then there are the rhymes … If you’re reading this book for the first time, you might be tempted to skip the rhymes. After all, who speaks in rhyme in real life? People might say things like “If punching parrots on the beak wasn’t too painful for pleasure, I’d land you a sockdolager on the muzzle that ud lay you out till Christmas,” but they don’t speak in rhyme.

But if you didn’t read them, you’d be missing a great deal. The characters break into song or rhyme whenever they’re deeply moved — that seems to be the rule; but the rhymes are so ingenious, the rhythms so muscular and catchy, that they’re impossible to resist. The high-toned ones are the most ludicrous of all. As Bunyip Bluegum says, in order to make peace between Bill and Sam after the unfortunate incident at breakfast:

“Then let the fist of Friendship

Be kept for Friendship’s foes.

Ne’er let that hand in anger land

On Friendship’s holy nose.”

There’s an exuberance, a gusto all through the book that’s irresistible. You can feel Lindsay carried away on the wings of his own energy.

At one point, indeed, he was carried beyond the bounds of courtesy. In the original text, during the furious trial scene toward the end of the book, the Judge says to the Usher:

“So I’ll tell you what I’ll do

You unmitigated Jew,

As a trifling satisfaction,

Why, I’ll beat you black and blue.”

The Usher is not Jewish. The Judge is being insulting. At the time when the book was written, few people would have raised an eyebrow at that use of the word — apart, of course, from Jews themselves. It was a casual, thoughtless, common way of speaking. But times change, and manners develop; and I think that if Lindsay were writing the book today, the warm, hearty, generous nature so evident in all the rest of the story would have found a different rhyme, or left out the line altogether, as this text does.

So who was Norman Lindsay?

He was born in 1879, in Victoria, Australia. He was interested in art from an early age, and by the time he was 16 he was already drawing for a newspaper in Melbourne. He drew all kinds of things: political cartoons, illustrations for editions of classic works of literature, and large, complicated, scandalous drawings that expressed his fervent belief in the importance of art and physical passion.

But he never made much impression on the art world. The fact is that he was a very old-fashioned kind of artist. At a time when the cubism of Picasso was all the rage, Lindsay was working in a way that had gone out of style 50 years before. However, that didn’t stop him, because he had a great cause, which was to persecute his mortal enemy, the wowsers. “Wowser” is the Australian word for a prim, narrow-minded, pompous, Puritanical, humorless, spoilsport sort of character. Uncle Wattleberry is a wowser. Lindsay loved to annoy the wowsers, and did it with great success all his long life. He fought them on principle, as the Puddin’-Owners fought the Puddin’-Thieves.

And he didn’t limit his activities to the visual arts: he wrote novels that shocked the wowsers as much as his drawings did. Most of the novels are as old-fashioned to a modern eye as the visual art, and as far as I know all of them are out of print; but it’s worth reading “The Cautious Amorist,” if you can find a copy, and “A Curate in Bohemia,” because there’s an innocence and a lighthearted energy about their “scandalous” nature that seems today — and there’s no other word for it — charming. And that would have surprised him and the wowsers alike.

Lindsay lived till he was 90, and fathered a dynasty of Australian artists and writers; he painted and sculpted and set up a printing press; he became a national institution. But many of those things have faded from view. His real monument is in “The Magic Pudding,” a book which he wrote because, he said, children liked eating and fighting, so they needed a story that put those things at the center of the action.

As I began by saying, I’ve been laughing at it for 50 years. If I live to be a hundred, it will still be my favorite children’s book. To quote Bill, finally: “There’s nothing this Puddin’ enjoys more than offering slices of himself to strangers.” And if you’re a hearty eater, sit yourself down with Bunyip and Bill and Sam, and help yourself to a slice. “Hearty eaters,” as Sam says, “are always welcome.”