To borrow a phrase from Pauline Kael, "Intimate Strangers" suggests bits of Alfred Hitchcock and bits of Woody Allen. But the wrong bits.

In Allen's "Another Woman" an air vent carried conversations between a psychiatrist and his patient from one apartment to another. It was a great premise for a farce or a mystery -- anything but the tortured WASP sob session Allen made of it.

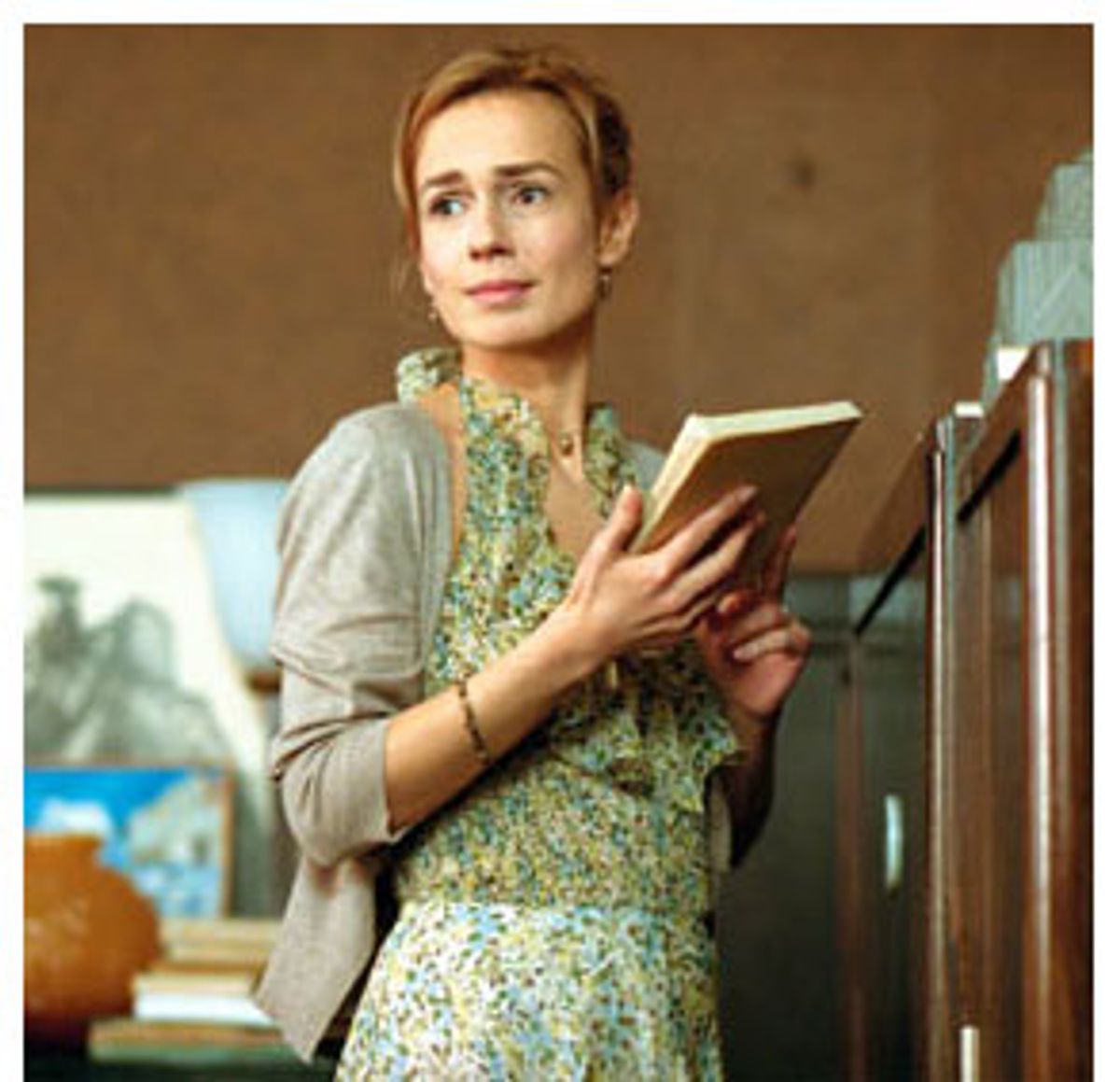

"Intimate Strangers" director Patrice Leconte and screenwriter Jerôme Tonnerre use a similar setup. Anna (Sandrine Bonnaire), whose troubled marriage has sent her in search of counseling, wanders into the office of a tax lawyer (Fabrice Luchini) instead of the office of the neighboring shrink and begins unloading her troubles. Thinking she wants advice on how to prepare her finances for an impending divorce, the lawyer, whose name is William, is deep into the role of good listener before he realizes that she's in the wrong office.

But William is hooked and agrees to see Anna again. Soon she's turning up at his office to offer tantalizing -- and maybe even true -- bits of her story. Even when she admits she knows William is really a tax lawyer, their meetings continue. For him, smitten but too discreet to admit it, these sessions are the only change he's had in ages. He lives in the same depressingly dark, tasteful office-apartment combo he has lived in since boyhood. He took over his father's business, even inheriting the secretary (Hélène Surgère), who's part mother hen, part busybody. The oppressiveness of the past seems to creep out of the carpets and furniture and draperies. Sunlight never seems to penetrate. You can't imagine anybody breathing in such heavy-spirited surroundings.

You don't know quite what these sessions mean for Anna. When she admits that she knew William wasn't a shrink when she rang his doorbell, when she tells him that her husband wants her to make love to other men and tell him about it, when there are hints that the car accident in which she wrecked her husband's leg wasn't an accident, Leconte seems to be setting you up for a Hitchcockian thriller about a repressed voyeur pulled into a calculating neurotic's game playing. And the potential that there is something criminal or even murderous about her game playing -- if it is game playing -- hovers over the movie.

The problem isn't just that there's no payoff, that the whole thing turns out a lot less sinister than it seems. The meticulousness that works so well in Hitchcock, typified by his remark that actually shooting films for him was an anticlimax, can seem as mechanical as one of the windup toys William collects. And finally, "Intimate Strangers" has about as much point as watching a monkey on a bike take a spin across the carpet.

That's frustrating, because the picture is very well made. It's about as carefully crafted as an ultimately vague trifle can be. Leconte restricts the superb cinematographer Eduardo Serra ("The Wings of the Dove," "Girl With a Pearl Earring") to a dark, oppressive palette, which is what the atmosphere calls for but is finally very stifling to watch. (When, toward the end of the movie, Serra gets to bask a bit in the sun of the south of France, I wanted to whimper in gratitude.) But there's no denying the care that's gone into the movie's look, the way the floating camera and the compositions that are just a little bit off (always cutting off a bit of someone's face) keep us on edge.

And Leconte has two fine lead performances. Bonnaire is in the unenviable position of playing an enigma who turns out to be not such an enigma. She's been used too much for that type of role. When Bonnaire's emotions are right on the surface -- as they were in Ré gis Wargnier's terrific melodrama "East-West," and in the two films she made for Jacques Rivette, "Secret Defense" and her stunning, tour de force performance as Joan of Arc in the director's massive two-part "Jeanne la Pucelle" -- then her unique, careworn style of beauty comes alive. The sense that the plot is always about to take a twist works to Bonnaire's advantage here. It makes us watch her closely. That the flickers of neuroses, seductiveness and fragility she shows don't ultimately key into anything doesn't diminish the delicacy with which she assays them.

As her secular confessor, Fabrice Luchini is remarkable. Luchini has an alert, rabbity look, with a distinctive combination of wide, glistening, sometimes fearful eyes and prim, set little mouth. At times he suggests a big baby who's gone to a finishing school for professionals. Everything from his conduct to his appearance is meticulous (you can't imagine him shaving -- not just because he has that babyish look but because you imagine he's willed the whiskers not to grow), held back, correct. And yet with just an inclination of his head or his body, he suggests how hungry he is for distraction, novelty, companionship. As Bonnaire is, Luchini is helped by what appear at first to be plot machinations -- you expect his eagerness is the thing that's going to lead him into trouble.

That the movie is finally nothing more than the story of an odd, symbiotic friendship makes "Intimate Strangers" a disappointment similar to Leconte's last film, "Man on the Train." Like "Intimate Strangers," that movie featured two fine performances (from Jean Rochefort and French rock 'n' roll icon Johnny Hallyday) and, with the metaphysical noir twist at the end, got swallowed up in vagueness.

Leconte is an odd case. It's hard to say whether he's a bourgeois entertainer who affects a certain attraction to the perverse, or a filmmaker concerned with obsession who gives his films the misleadingly placid air of bourgeois entertainment. (Leconte's "Monsieur Hire," a remake of Julien Duvivier's classic thriller "Panique," was best when it explored the clammy, repressed sexuality that was implicit in the original.)

The answer, I think, is that Leconte is a bit of both. I haven't enjoyed any of his movies as much as I did his "Girl on the Bridge," a wonderful moonstruck comedy about the giddy certainty of romantics who believe their soul mate awaits them. I've never sat through one of his movies, though, without finding something -- a performance, a bit of direction, the cinematography -- that made it worthwhile.

Leconte is talented enough to make you hope he'll get it right each time out (and maybe he did in some of his films of the past few years that we haven't seen here, like the thriller "Half a Chance," "Felix and Lola" and "Rues des Plaisirs"). But his letdowns are almost never washouts.

Shares