Beth Kephart, a literary nonfiction writer, loves reading so much that she devours several books a week. But her son, Jeremy, did not automatically follow suit: He preferred listening to Kephart read aloud to doing it on his own. At 9, he was unimpressed by the novels his mother had loved as a kid — classics like “Charlotte’s Web” — preferring instead to read nonfiction about knights and cars and airplanes.

“I didn’t mind, I just wanted to broaden him,” Kephart says. She sees literature — along with music, art and other creative fields — as a way kids can learn to understand life’s large issues, “to ask the big questions and to look to themselves for answers.” So she gave Jeremy ample time and gentle encouragement until, eventually, he began to read novels on his own, to write stories and poems, even to make his own movies. Not in pursuit of grades or test scores or admission to exclusive schools, but for fun.

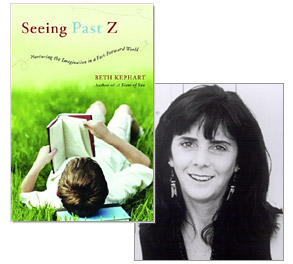

In her fourth book, “Seeing Past Z: Nurturing the Imagination in a Fast-Forward World,” Kephart uses the story of Jeremy’s creative development as a springboard for arguing that many children are robbed of the chance to develop their own creativity. Although Kephart includes video games and television among the culprits, her particular foe is a child’s busy schedule — filled with lessons and activities and college preparation — that she believes is imposed by ambitious parents across the country, including many in her own affluent community outside Philadelphia.

Kephart chronicled Jeremy’s early struggle with pervasive developmental disorder, a condition often mistaken — much to Kephart’s frustration — for autism. “A Slant of Sun,” a 1998 National Book Award finalist, ends with Jeremy at 7, having overcome those difficulties. Now, in “Seeing Past Z,” Jeremy has become a typical boy who attends public school, plays soccer, and plays with friends. He exhibits a child’s active imagination: He invents complex personal histories for the characters in a board game; he asks probing questions that his parents can’t always answer. The book describes how, with the help of Kephart and her husband, Bill, that imagination evolves (although she readily admits that their efforts weren’t unusually heroic or elaborate, but rather the basic Parenting 101 support that busy schedules sometimes force to the wayside.)

Her campaign on behalf of children’s creative growth did not stop with Jeremy: Since he was 9 she has been giving workshops in which she leads groups of neighborhood kids in activities centered around books. This summer, she has expanded the group to include kids from lower-income neighborhoods of Philadelphia.

“I’m writing it with the great prayer that other parents who are reading it will say, Gosh, it looks like fun to start a neighborhood writing group for kids, or a neighborhood music group for kids, or a neighborhood pottery group for kids,” she says. To that end, she includes an appendix full of ideas for anyone interested in holding similar workshops, along with samples of writing by the kids she has taught.

The title of “Seeing Past Z” alludes to line from a Dr. Seuss book: “In the places I go there are things that I see that I never could spell if I stopped with the Z.” Kephart urges parents to help their children find those places beyond Z — beyond the test scores and prizes and résumé-building — to grow in unexpected ways. Kephart spoke to Salon in late July from her home in Philadelphia.

What made you want to write the book? How did you come up with the idea?

When I first began to write the book — which developed out of essays that I began writing about five years ago — I was looking at the emergence of the imagination in my son. I was interested in all of the elements that fall into place as the creative spirit arises. I would read stories to Jeremy — the Harry Potter books, books by Roald Dahl. He also liked the Lemony Snicket books. He finally got a desire to read realistic kids’ novels on his own. And eventually he began writing his own stories. He started out with made-up newspaper headline stories, went into the comic misadventures of cartoonish characters — funny things that would happen to kids; there would be supernatural powers involved — then moved on to movie synopses, with lists of who would star, who would direct. Now he’s writing a series of detective stories for TV, so they are all straight dialogue and setup.

At the same time that I was doing that, I was teaching reading and writing to the kids that come to my house and watching what happened to them as they worked together to build a community. The kids would talk about how they feel about the books, how the stories relate to their own experience. You could see them being generous listeners, building friendships that held beyond the workshops themselves.

I live on the Main Line in Philadelphia, a predominantly white, upper-middle-class community [and the setting for the 1939 Katharine Hepburn film “The Philadelphia Story”] that has many, many wonderful schools and opportunities for kids — and a whole lot of pressure on these kids to perform, to build a résumé. All of these pressures, I began to believe, were denying kids the right to chart their own course, to dream their own dreams, and to just have time to think.

So you were seeing too much emphasis on goal versus process, on what you achieve rather than what you do along the way. Do you believe that one excludes the other, necessarily?

What I’m most concerned about are parents who insinuate their own ambitions into their children’s lives. I think that a child who wants to be a violinist, and that’s their dream from the age of 3, and they take that on and they live that dream creatively and it is their own dream — I think that is really great if it’s managed in the right way. My concern is more the parents who say, “You will take Japanese to make you interesting, you will do this, you will do that.”

You mention in the book that people actually have suggested that, by taking a less goal-oriented approach, you would hurt your son’s future prospects.

I am seen as sort of this marginal weird mother on the outside who is not booking her son into every imaginable résumé-building category. I’m up against it all the time, frankly, with the kids who come to my workshop. There are parents — not all of them, but there’s a good percentage — whose kids come who say, “But what are you doing to help them with their SAT scores?”

When I was working on the book and I would tell people what it was about, I had a few parents say, “But it’s all about getting into Harvard. If you’re giving him time to dream and write stories that may or may not be published, you’re not giving him the competitive edge. He will have a disappointing adulthood. You’re not giving him the platform to stand on and be successful.”

I don’t mean to sound like an extremist. Certainly, the book is not extreme. I think it’s a gentle book, it’s a “what if?” book, it’s a series of questions, and it is the story of what happens in one family’s life when certain priorities were chosen.

We didn’t schedule him. We made the choice. We looked around and said, “Yes, he’d probably benefit from having clarinet on his résumé or something,” but he wasn’t interested in clarinet, so we didn’t push him. We had him take piano for six months, but he wasn’t interested in pursuing it, so we said fine. We didn’t push him. This year, we’re not putting him in summer school, which is huge around here.

How much responsibility do you as a parent have, does any parent have, for guiding her child this way?

We cannot ultimately build the children of our dreams. Our responsibility is to be there, to share what we love with them, to listen to them as they emerge, to answer questions, and to learn when to step away. If there’s another thematic line that goes through this book, it’s about a mother of an only child who is learning to step back, who is learning to say, “You’re a lyrical writer, and your kid is interested in spy stories and he’s interested in action and he’s interested in things that certainly you didn’t create in him. You’ve had conversations, you know where he’s going, you know that he’s got a good soul — and don’t hang over his work too heavily. Step back.”

Do you have any particular career desires for Jeremy?

They have to come from him. Right now, he would like to be in film, and what he’s particularly interested in is sound editing. This summer, when Jeremy is home, Jeremy and I spend a part of every morning reading classic short stories and talking about them. And then Jeremy and Bill spend in the afternoon time looking at all the computer editing software; he’s actually building a film trailer right now and just having fun with that. And I think that the exposure to all the stories and to the community that I’ve built with him has given him some options. He’s thinking about sound and story. Fantastic! I wish I had that mind.

Do you think that other parents would be able to do the kinds of things that you’re able to do with Jeremy? Would it fit into any family’s life?

I’ve gotten some really nice e-mails, and one of the things the readers are interested in is how you build a neighborhood workshop. Well, these are people who have jobs, and they do things at night and their children have soccer, too, but they are able to find an hour or two during the week, and maybe it’s just for six weeks over the summer. Schedules are schedules. Jobs are jobs. I understand that and I thoroughly respect that. It’s about what you do in the free time that you have, and if you can find an hour or two a week to encourage the child to read or to look into what the child’s writing, if you can find some time to build a workshop for even a month, or four Saturdays in the spring, it is so rewarding!

So you devised a workshop. Tell me how that evolved.

When Jeremy was in fourth grade, I was trained as a discussion leader for Junior Great Books [a nonprofit reading and discussion program offered in schools around the country, often led by parent volunteers]. I got 14 kids in fourth grade, and on Tuesday afternoons I would go over to the school and read the wonderful books the Junior Great Books program put together.

After a year went by I thought, hey, if they’ll have me, if their parents would be interested, we’re going to do more than just read out loud and discuss. We’re going to think about how writers work, we’re going to look at, for example, irony and trick endings, we’re going to see dialect, the tools of writing. And then let’s give the kids some time to write on their own.

What were you doing as a writer during this time? Were you working from home?

Yes, working from home on books, magazine articles, and the business I run with my husband, a marketing communications firm.

How did you come up with the ideas for workshop activities?

I would be lying to you if I said that it was a science. I read endlessly and I’m always thinking about, What part of this book would I like to share with someone else? I happened upon a Norse creation myth about two months ago. It wasn’t age appropriate for this particular group of children. But creation myths, absolutely! Let’s do that, that’s great! So I can’t tell you that I sit here and think in some kind of vacuum that I know what to do. I’m just hungry and I’m always looking for something.

Sometimes I’m scared. Late Friday night I’m thinking, “Is it going to work?” I don’t pretend that I’m the expert. I’m making it up as I go along, and that is the point. Any parent who loves books and kids could do the same.

All four of your books are about your life. [Her others, “Into the Tangle of Friendship” and “Still Love in Strange Places,” are about friendship and marriage, respectively.] But you say you don’t like to use the word “memoir” to describe your books. Why not?

Memoir can resemble being cornered in a room with someone at a party and they keep talking and you just say, “Uh-huh, uh-huh.” I don’t believe in publishing one’s personal story just for the sake of telling one’s personal story. I am saying to the reader, join me in a search. I’m going to write this in a way that leaves room for you to draw your own conclusion. I hope my work unlocks for the reader their own memories, their own ideas, and their own quest.

Two of your books are about Jeremy. Is there something about motherhood you find particularly inspiring?

Jeremy was a gorgeous baby. We all feel that way — right? — about our kids, and I couldn’t help putting it down in words. I use words as many people use a camera. I don’t believe I really know how special something is until I start to form the words for it. I write to understand.

How does Jeremy feel about having you write about him?

I would never put anything into any of my books — which have featured my son as well as my husband, friends and some family — unless I know it’s OK with them. Is that cool? Does that make me commercially, you know, sexy? No, it doesn’t. But I consider myself to be a person of the world first and a writer way back there, third or fourth. In this case, he was very excited, because he was happy to have the things that are important to him be so important to me that I would write about them.

How did you decide to include, at the end, the kids’ work?

Because they were so excited about the possibility of having their work put together in that way, and because I wanted to very honestly show this is what comes from the workshop suggestions. Some of it’s unexpected and some of it you’re thinking, hmm, I didn’t mean to inspire that. But it’s what comes, naturally, unedited. These are the voices of children speaking, when unleashed.