After 30 long years, Craig Nova has yet to Garp, but he’s Gatsby’d more than once. In other words, he’s a novelist who has yet to write a supermarket bestseller like “The World According to Garp,” but he has written at least two American classics that will likely resonate after his death, the way the poor-selling “Great Gatsby” did for poor ol’ F. Scott Fitzgerald.

The pair of Nova books that stand out immediately are “The Good Son” (1982) and “The Congressman’s Daughter” (1986). They both concern American politics and wealthy families. “The Good Son” is about a young WWII fighter pilot, born to a first-generation millionaire. The book begins: “My father is a coarse, charming man, a lawyer, and a good one, and when I was flying over the desert and the German pursuit pilot began pouring round after round into my plane (a P-40), I was thinking of how I learned to drive, and how it affected my father.”

“The Congressman’s Daughter” concerns a New England politician’s daughter forced into a shotgun marriage. Its opening sentence is brief: “I know more secrets than any man I have ever met.” These two titles belong to the “born to the purple” novels of Caucasians like Louis Auchincloss and Ward Just, although just like Gatsby, Nova’s characters go slumming. The novelist and Seattle critic Michael Upchurch believes that both “The Good Son” and “The Congressman’s Daughter” are “the all-American prose equivalent to Beethoven’s Symphonies … there’s a genuinely classical grandeur to Nova’s tales of erotic derailment and titanic family conflict.” After those titles, Nova wrote more than a few more novels. In 1994 came Nova’s seventh, “The Book of Dreams.” Upchurch, smart guy that he is, called this one a masterpiece too. “The Book of Dreams” is a brilliant Hollywood novel about a “Last Tycoon”-style movie producer, a hit man, and a performing elephant run amok in LA. It is up there with Raymond Chandler’s “Little Sister” and Bruce Wagner’s “Force Majeure.” Or to return to Upchurch’s musical reference, “The Book of Dreams” is less Beethoven and more “Morrison Hotel,” by the Doors. Although the bulk of Nova’s oeuvre is set in the eastern part of the country, he himself was raised in Hollywood in the 1960s. “I would race Steve McQueen on Mulholland Drive,” he says. “I had a ’55 Chevrolet, and McQueen had an AC Cobra. He would let me follow him for a little bit, then he would take off and wave to me.”

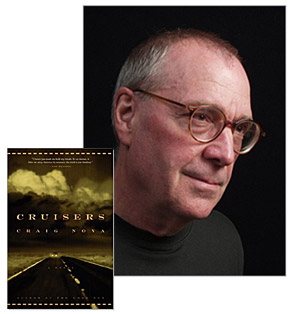

Since his Hollywood novel 10 years ago, Nova has written (among other things) a fishing memoir, a science fiction novel, and his newest and 12th novel, “Cruisers” — a modern exercise in classic existentialism à la Albert Camus. Nova’s title concerns a pair of antagonists dueling and dealing with American desires and American death along a Vermont highway.

I suspect the reason Nova isn’t a bigger draw at, say, Barnes & Noble, is because he’s difficult to peg. I spoke to Nova about this on the phone. He lives in Putney, Vt., located near the twin axes of the Massachusetts and New Hampshire borders. Coincidentally, I lived in Putney during Gerald Ford’s last year in office. As I remember, a rustic sawmill sits in the center of town. Down the road, a boulder lies marked with a red-painted devil’s head. I recall that a slinky European car used to buzz around with personalized Vermont plates that read GARP. It turned out that John Irving lived in Putney and was finishing “The World According to Garp” at the time. Nova is friends with Irving and moved to Putney on the latter’s recommendation.

If Nova himself hasn’t Garped yet, he at least lives in the right town.

What book of yours should uninitiated readers begin with?

That’s a tough question. All writers think their last book is their best because of the process of self-hypnosis that goes into it. The sense of immediacy. So I think this new book, “Cruisers,” is right in there. Tolstoy said someplace that “Many write books, but few are ashamed of them.” I am the exception to that. There are some books that I’d like to have back.

Which ones?

I published my first book when I was 26, so I had the misfortune of growing up in public as a writer. I’d like to retrieve one called “Turkey Hash” (1972), and another titled “Incandescence” (1989). I didn’t really grow up until my fourth novel, “The Good Son,” which was a big jump from the early books. It’s not that the early ones were insincere; they were just written by someone not sufficiently grown up to understand what it really means to write a novel. [Pauses.] Although I’m not sure if I’m at that point yet at 59.

Why didn’t you become one of those so-called California writers?

I was just thinking about that this morning — the influence that Los Angeles has on a writer who grew up there. I bet for every writer there is a “Los Angeles,” a place [where] you’re really in touch with anxiety and fear and the ominous. In fact I just got off the plane from L.A. — I went out there to do some stuff for the book. While I was there, it all came back from when I was growing up. You don’t know if the place is going to burn down, blow up, or be swallowed by the ocean. One of the things that I like to do in books is invoke the ominous. It’s a way of getting control of it, I suppose.

I was a California kid during the late 1960s and early 1970s. For me, the East Coast and New England were exotic America. I’d never been further east than Wisconsin.

Me too. In fact I grew up on this weird mythology of the East. My mother was born in Provincetown. Her grandfather had a farm in Vermont. When I was growing up in Hollywood she was always telling me stories about Vermont and blueberries and maple syrup and pancakes. Even then I knew there had to be more to the East than that, but the strange thing with the mythology was that even though I knew it was bogus, somehow it still took hold. Here I am.

I love the West for the desert. I love the Raymond Chandler mystique.

I left my family pretty young and moved in with the family of a friend of mine. His father was a screenwriter. When I left L.A. for New York to become a writer, he looked at me with tears in his eyes and said, “Whatever you do, don’t come back here.”

Did he mean, “Don’t come back here to write screenplays”?

Exactly. It’s a very dangerous thing to do. You know writers believe in merit and they like to take chances. This is a combination that is absolutely inflammatory and likely to incinerate every aspect of your life if you work for Hollywood. You’re willing to work harder than anyone else. You think you know that book better than anyone else. You think if push comes to shove that you’ll be able to charm people into doing what has to be done. Hollywood is — how can I say? I made a little money there, but it’s a very dangerous way for a writer to make money.

“The Good Son” and “The Congressman’s Daughter” are these great political genre novels about people with money and power, but some of your other books, like the new one “Cruisers,” are about the working class.

For an experiment, I did two socioeconomical versions of the same story, “The Good Son” and “Trombone” (1992). They’re both father-son stories modulated by differences in money and expectations, and image and power. One of the things about writers is they don’t fit in anyplace. That’s not to say that they’re aloof. They’re just comfortable/uncomfortable anywhere. [Pauses.] That’s why I live in the sticks.

Let’s talk about “Cruisers.” The publicity materials say that the novel is based on a true story, but they don’t say what the story is.

It’s something that got a fair amount of publicity in New England. A guy at the Canadian border went nuts and shut up a judge, a newspaper reporter, and a couple of cops. Then he trapped four other cops in a very bad spot. It happened the way I described it in the book. He stole a police car. He went up to the end of a wooded road. He put the radio on very loud. Walked back the way he had come, and then went up on a hill. Soon or later, the cops would come in and he would be behind them. One of those cops was the son of friend of mine. After it happened my friend wanted me to go up and see where his son had been trapped. I stood up there and could see where the guy stood. Where the cops had been pinned down. A couple of them had gotten shot. It was the most ominous place I had ever been. There was something in the air.

I was writing another book at the time, but as the years went by I kept thinking about that place. And I thought how it was that two people could meet there under those circumstances — a young vital, charismatic cop, and a man from the American depths. To write the novel, I began riding with a state trooper on [Highway] 91. He was one of the guys who had been trapped up there.

91 — does that go straight up to Canada?

Yeah. It seems like such an innocent thing — a highway in Vermont. But it isn’t. There’s heroin traffic between Burlington [Vt.] and Springfield [a working-class town in Massachusetts]. Very heavy-duty because the price of heroin in Burlington is twice what it is in Springfield. You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to figure out you can make a lot of money by buying in Springfield and bringing it to Burlington.

You know who Frank Kohler, your psychopath, reminded me of? The novelist James Ellroy.

Really? I like Ellroy. There is an intensity in his work that I really admire.

I mention Ellroy because when he was a kid his mother was murdered like Kohler’s mother had been.

I knew that. Actually the detail about Kohler’s mom came from a detail that I saw in a police barracks about a body in a trunk that had been found at the side of the river. [Pauses.] You know as we talk, I think one of the things that happens as you get older is there is a kind of distilling process and you give in to your influences. You internalized them so completely that they don’t feel like influences anymore but something that comes from yourself. One of this book’s influences is Albert Camus. The central ethical question in his work is “What do we do? We’re born. We die. We don’t like that.” Under those circumstances how are we obligated to other people? My character Russell [the highway patrol officer] has obligations to a woman he’s fallen in love with.

My other influence is Graham Greene. No one understood anxiety of the modern age like Greene did. And his books are still all in print. Everybody reads them. “Brighton Rock” was in my mind a lot when I was writing this book. Actually my wildest and most enthusiastic high about this book is I would like to think of it as a collaboration between me and Graham Greene and Albert Camus.

How much research do you do for each novel?

“Cruisers” is kind of an exception. The answer is usually not much. As a novelist you know you’re always looking for stories. Since this book was inspired by this thing, I felt you have to know what happens at night in a patrol car. How do you get the shotgun out? How does the radio work? What really goes on out there?

Sometimes you can just make stuff up and get it right. My first book is about a kid driving a cab with a dog. Now I’ve never driven a cab, let alone with a dog. I did no research. Recently I met the novelist Andrew Vachss. It turns out he once did drive a cab in New York, with his dog. I was expecting him to say, “You know nothing about cabs or dogs.” Instead he said he really dug my book.

The truth is, it works both ways. Stephen Crane never went to the Civil War. It is not necessary to experience everything you write about. In some ways it can be a crutch. In fact, I stopped hanging around with that trooper because he was so charismatic that he was taking over “Cruisers.” By the way, I did once drive a cab in New York City. That is a peculiar job that’s much like being a cop. People take cabs in emergencies. They get in a cab and they’re bleeding, and you take them to the hospital and they run in and you’re left with six bucks on the meter, and blood in the back seat. It can be an ominous job.

Why is the ominous such a theme?

It certainly seems to be much on my mind this morning. In this post-postmodern age, or post-post-postmodern age — whatever age we are living in — there are new demands on novelists. There are a million ways that writers try to face up to those demands. The one that I’ve picked out for me is storytelling, trying to set up a book where the reader wants to turn the pages and find out what is going to happen, yet at the same time they trust you. They know you may lead them into some scary places, but you’re going to bring them home all right. They know you’re not going to rape their sensibilities without nourishing their values a little bit.

Have you ever seen the old 1930s movie “I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang”?

Yes. The Paul Muni movie.

I saw it recently and remembered what it was like to take a fictional trip and be left in nothing but despair.

I think that’s one of the things that a good fiction writer doesn’t do. They find a way to take you there and then leave you informed but not violated. You’ve seen things that are true to what is known as the human condition, but not in such a way that you want to go out and get drunk. That is why Graham Greene is so important. You read his books and they’re pretty damn grim, but there is something in his sensitivity that makes his books enjoyable. I think this sensitivity is even more important with movies.

For some reason I’m thinking of this modern Japanese movie I saw about where people go after they die [“After Life”]. They spend a week in this purgatory where they have to remember one moment that represents their life — which is going to be recorded in this kind of celestial film archive. So you watch them choosing that one moment from their lives. Absolutely haunting. Only the Japanese could get away with something like that.

So for your movie would you choose the moment around a book being published? Or is the launch of new book now a casual experience for you?

No, I get wound up. No one can sit for two and a half years in a room trying to do their best work and then, “Well, you know I’m totally indifferent to what the reception is.” It’s impossible. The difficult part of the writing life is the up-and-down part. You go through a very bad time, and then you publish a book, and it’s optioned for the movies and sells for translation. You’re not rich, but you’re not sweating bullets to pay the mortgage. And you think that somehow you’ve gotten beyond the plateau where you have to worry about money so much.

Then a couple years go by and you’re right back down in the depths — you’re borrowing on the house to finish a book. You’re terrified to put gas in the car. And then for reasons you don’t understand, for some reason it all picks up and goes back up again. It’s the starting and stopping part that I find the most difficult. I really do. I am a writer who has published 11 novels and who isn’t very famous — not yet anyway.