Just after 7:30 Tuesday night, John Kerry finished a string of satellite TV interviews at the Westin Hotel then climbed in the back of a Secret Service Chevy Suburban for the ride to his home on Louisburg Square. Campaign manager Mary Beth Cahill and advisor Bob Shrum were with him, and they talked along the way about all of the supporters who were lining the streets to watch the motorcade pass by. In the final days of the campaign, Kerry often seemed moved by the signs of support he was seeing. Inside the Suburban, Shrum turned to Kerry and said, "I think we're going to make it." Kerry looked out the window. "Look at all the people," he said.

Wednesday afternoon inside Faneuil Hall, it all seemed so far away.

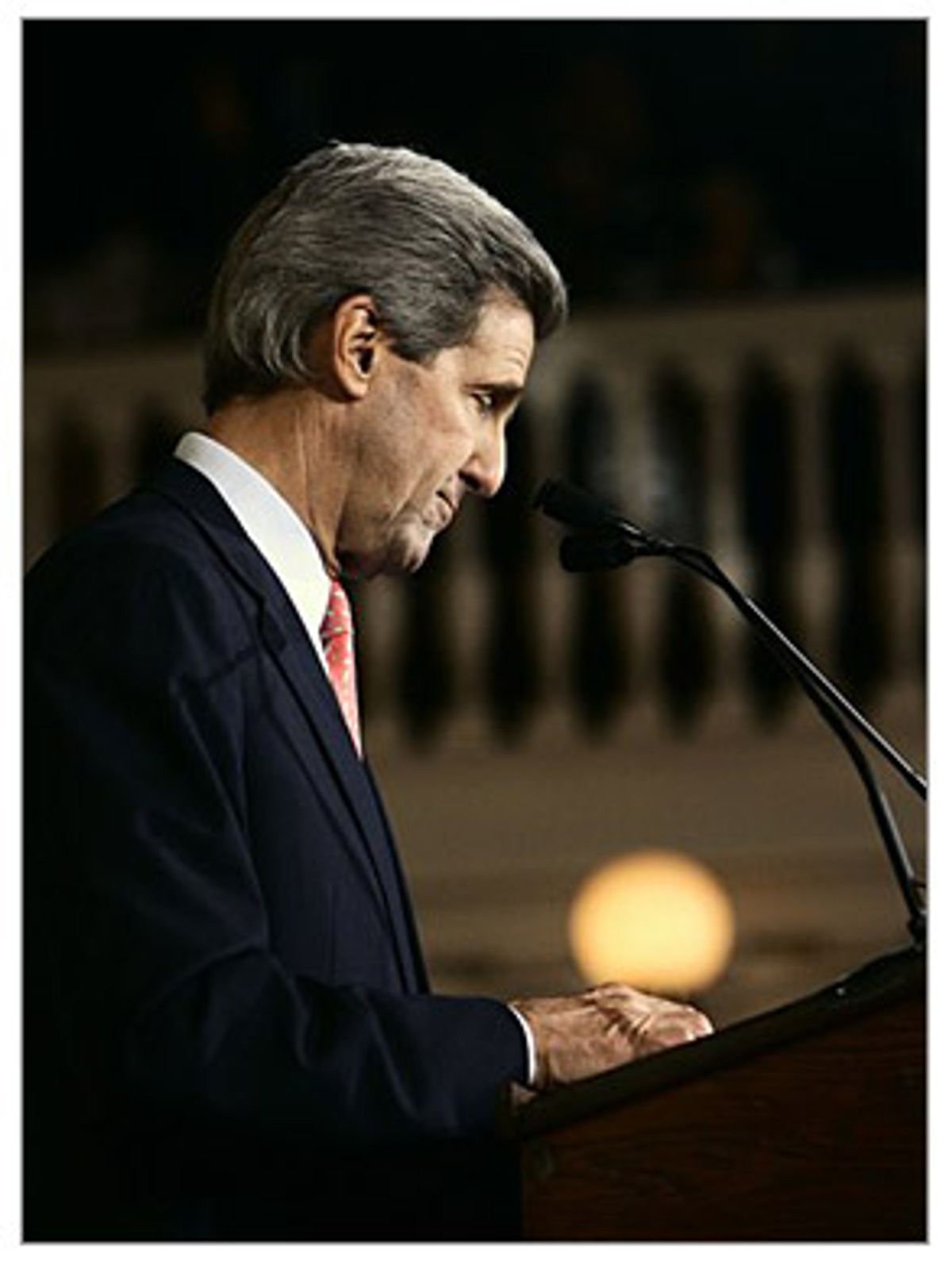

From behind a simple wooden lectern, John Kerry conceded the election to George W. Bush. "We worked hard and we fought hard, and I wish that things had turned out a little differently," Kerry said. "But in an American election, there are no losers, because whether or not our candidates are successful, the next morning we all wake up as Americans. That is the greatest privilege and the most remarkable good fortune that can come to us on earth. But with that gift also comes obligation. We are required now to work together for the good of our country."

It's not what Kerry or his staff planned to be doing Wednesday. They were so sure of victory that they had no contingency plan for a day-after concession speech. As reporters and supporters crowded to get into Faneuil Hall Wednesday afternoon, construction crews were still racing to build a portable platform for the TV cameras. Kerry's teleprompter screens were propped up on makeshift bases made from overturned mail bins.

Just after Kerry finished speaking, Cahill slipped out the back stairs, crying. Shrum talked with a small group of reporters, explaining how Kerry and his advisors watched it all slip slowly away from them. "We thought for the last several days of the campaign that we were going to do it," Shrum said. "Any of you who rode on the airplane with us knew that." He was right, of course. As Kerry made final campaign stops in Ohio and Wisconsin early Tuesday morning, his staff seemed giddy with hope. Mike McCurry and Stephanie Cutter danced on the tarmac in LaCrosse, Wis., and Kerry himself was so confident, so relaxed, Tuesday that he had a beer with lunch before setting off for that final round of TV interviews.

As Kerry did the interviews, the news from the field just kept getting better. "We had the exit polls, we had our own data, we had a lot of public data," Shrum said. "It all pointed in the same direction." As evening came in Boston, young Kerry staffers started talking openly about their hopes for a job in the new administration. Kerry was briefed on the exit polls as his interviews ended, but Shrum said he stayed "even." Kerry remembers all the polls that showed him with no chance of beating Howard Dean in the Democratic primaries. "He believes in real votes," Shrum said. "Anybody who saw the numbers he saw in Iowa and New Hampshire wants to wait to see what the real votes are."

So they waited. The early returns were predictable. The networks called Georgia and Indiana and Kentucky. They called Vermont for Kerry, but they were so slow to call West Virginia that Democrats watching returns in Copley Square began to think about some kind of Kerry landslide.

But as the hours ticked away, Kerry's closest advisors began to see the race move away from them. "I don't know that there was any one moment," Shrum said Wednesday. "I got a sinking feeling when the statisticians and research people began saying, 'Well, yeah, we're probably going to carry Florida, but it's looking a little redder.' And then Florida slipped away, and they said, 'Well, we're still going to carry Ohio on this data, but it's getting a little redder.'"

With the vote count turning against them in Ohio, Kerry's advisors started talking about the provisional ballots that had not yet been counted. There were a lot of them -- maybe as many as 250,000 -- and Kerry's advisors thought they would cut dramatically in his favor. They started thinking about their options. Cahill ran what Shrum called a "series of meetings" at the Westin Hotel. They talked about "what the real situation in Ohio was, how many provisional ballots there were, and what the gap is," Shrum said. The consensus among the campaign advisors: "If we could win this fight, if we could prevail on it, we would continue."

At about 2:30 a.m., the campaign sent John Edwards out to Copley Square, where a few hundred stragglers from the victory celebration that never was stood waiting in the rain. "It's been a long night," he said, "but we've waited four years for this victory, we can wait one more night."

Kerry's advisors kept meeting and talking, watching the last precinct reports from Ohio and doing the math on the provisional ballots. But by 4 a.m., it was pretty clear to them that victory would not come. "You could smell it in the meeting in the middle of the night," Shrum said, "but you still have to do your due diligence." Kerry and his top advisors went to bed while the lawyers and the number crunchers stayed up, watching and working.

Cahill called another meeting for about 8 a.m. Wednesday. At that point, Shrum said, "it became clear that we couldn't possibly make up the difference." Shrum and Cahill drove to Kerry's home, and they briefed him on where things stood. "There was no dissension," Shrum said. "Why would you stay in? If you count all the votes, you're not going to win. Senator Kerry said, 'Let's give the speech,' and we said 'fine.'"

The meeting ended, and Kerry called Bush to congratulate him. "We had a good conversation," Kerry said. "We talked about the danger of division in our country and the need -- the desperate need -- for unity, for finding the common ground, coming together."

Three hours later, Shrum and Cahill and the rest of Kerry's staff gathered inside Faneuil Hall to hear their man concede. As they waited for Kerry and his family to arrive, younger staffers who were thinking about jobs in Washington just 24 hours ago began talking about what they'd do tomorrow. There were homes to return to, clothes to wash and bills to pay. When Kerry and Edwards walked into the hall at about 2 p.m. the staffers stood and clapped for what seemed like forever, as if by doing so they could postpone the words that they knew would be coming.

Edwards went first, and in what amounted to the first campaign speech of the 2008 race, he reminded everyone in the hall of the reason Kerry put him on the ticket in the first place. Edwards was eloquent and moving, and he vowed to fight on. "I've learned a lot of lessons in my life," he said. "There will always be heartache and trauma -- you can't make it go away. But people of good and strong will can make a difference ... One lesson is sad, and one is inspiring. Because we are Americans, we choose to be inspired. We choose to be inspired because we know that we can do better -- because this is America, where everything is still possible. And in the heartache we feel today resides an eternal hope for the country we're going to fight for and the country we're going to build together."

He told the young people in the room: "You can be disappointed, but you cannot walk away. This fight has just begun."

Kerry was more conciliatory. He thanked his family, his staff, the volunteers who worked for him and the ordinary citizens who stood in line for hours Tuesday to cast their votes. "In America, it is vital that every vote count and that every vote be counted," he said. "But the outcome should be decided by voters, not a protracted legal process. I would not give up this fight if there was a chance that we would prevail."

The cold math of Ohio made the answer clear: "We cannot win this election," Kerry said.

Kerry said he would continue to press the issues that mattered in his campaign -- more jobs, more affordable healthcare, a foreign policy that will "restore America's reputation in the world" -- and he called on his supporters to put aside the sadness and bitterness they're feeling today in order to help move America forward in the years to come.

"In the days ahead, we must find common cause," he said. "We must join in common effort, without remorse or recrimination, without anger or rancor. America is in need of unity and longing for a larger measure of compassion. I hope President Bush will advance those values in the coming years. I pledge to do my part to try to bridge the partisan divide. I know this is a difficult time for my supporters, but I ask them, all of you, to join me in doing that."

It was well said and heartfelt, but everyone inside Faneuil Hall knew exactly how hard this is going to be. As Kerry's staffers said their goodbyes and filed out into whatever world awaits them, they walked past a college kid standing across the way with a hand-lettered sign. It said: "Democracy doesn't work."

Shares