In a low-slung, brick-and-glass building in Van Nuys, Calif., a small group of executives is screening candidates for one of the world's top jobs. With millions of dollars on the line and no margin for error, the interviewing steers clear of standard "Where do you see yourself in five years?" lines of inquiry and goes directly to more rigorous questioning. "So," one asks candidate Rob Cieslinski, "are you more the ass man or the breast guy?"

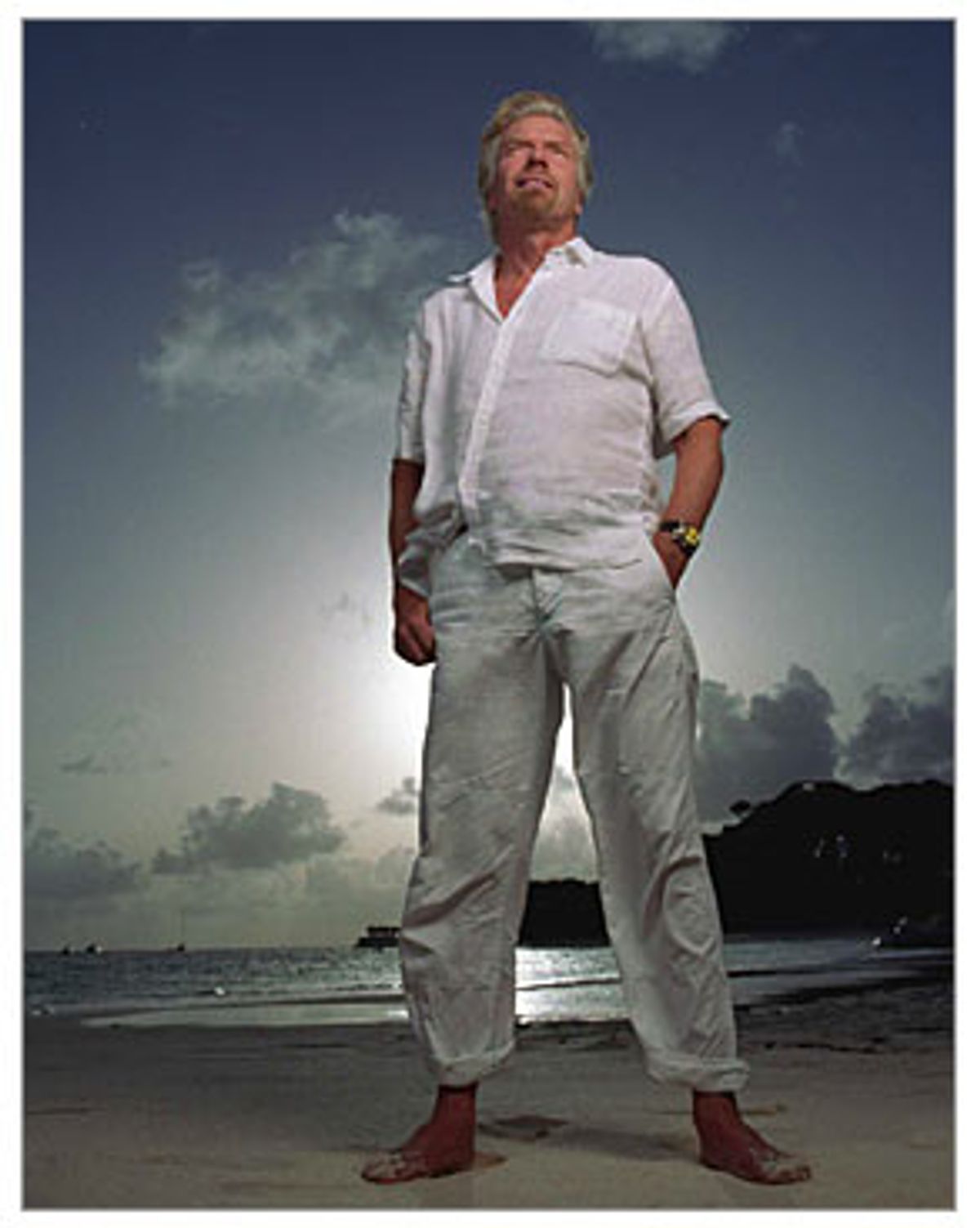

Rob and the four others who will be interviewed today are among 35 finalists who have been invited to the Los Angeles headquarters of Bunim/Murray Productions for a make-or-break shot at joining the cast of "The Rebel Billionaire," which is scheduled to premiere Tuesday at 8 p.m. The show, Fox's let's-take-it-outside challenge to NBC's reality blockbuster "The Apprentice," features Sir Richard Branson in the role of Donald Trump's would-be pummeler, and will shrewdly play to the British tycoon's free-spirited personality. Branson had dinner, once, with Trump, and came away struck by how full of spite the Donald is. "That's an approach," Sir Richard told us. "It's not our approach. I think that business is life. In life you treat people well. You learn basic forgiveness."

Despite Fox's wager that Branson's magnetism will win the show hefty ratings, ultimately its success is being staked on something more deliberate and far less public: the interviews unfolding inside this no-frills casting room just north of the Hollywood Hills. Reality TV has always been a casting director's medium, but in recent years it has evolved into a near-science, the most telling innovation being the use of psychologists to pinpoint character types and predict how they'll behave. "Billionaire" is hewing to a model, pioneered by "Apprentice," that takes casting to yet another level. With these shows, the object is not simply to generate compelling TV. It's to yield someone who, when the cameras stop rolling at the end of 13 episodes, can assume a well-compensated role in Trump's organization or Branson's. (Where the prize on "Apprentice" was a $250,000 salary working for Trump, "Billionaire" will lavish $1 million and Branson's job as president of his conglomerate on the winner.) No longer is it enough to throw a bunch of outgoing, narcissistic bartenders and personal trainers together, stir, and wait for the explosion. At Bunim/Murray, which produced the seminal reality shows "The Real World" and "Road Rules," the casting team knows precisely how to bore into psychological bedrock -- by poking, prodding and picking fights.

Thus, the existential question Rob Cieslinski now faces: breasts vs. buttocks. T or A? Rob, first spotted at an open casting event in Denver, possesses what real estate agents might call curb appeal. At 6-foot-5 and 250 pounds, with a Marvel Comics physique, the 28-year-old quickly stood out among the 10,000 people applying for the show's 16 slots. He's decent, reasonable. There's no doubt Rob is psychologically healthy. The question is: Is he too healthy?

"Can you give him a couple shots of espresso?" Sasha Alpert asks, leaning into a microphone connected to the interviewer's earpiece. "Rev it up a little."

Alpert, the chief casting pro at Bunim/Murray, bears a favorable resemblance to the actress Carrie Fisher; girlish and intuitive, she pioneered the casting methods now standard to the industry, and many of her protégés now occupy casting director chairs at rival shows. In an arctically air-conditioned room, she and the rest of casting team sit around a conference table, shivering and watching Rob on a closed-circuit TV. The table is cluttered with bowls of dried fruit and candy and fat dossiers about each applicant. Someone comments that Rob's buzz cut and blocky head make him look like Frankenstein's monster. "He's nicer," says another casting director, "so I called him Frankenberry."

Reality TV people like to enshroud the casting process in mystique, partly to deter applicants from gaming the system, but also to conceal the mercilessly reductive psychoanalyzing at its core. Just minutes into my privileged backstage view, it's clear that the sausage making isn't pretty. Among the "Billionaire" team's internal jottings about Rob so far: "A bit of a meathead (but in a good way)"; "Seems pretty full of himself (could work well in the show)"; and "Don't know if he's unique enough ... he's a little bland."

For a casting director, the elusive sweet spot is someone who walks the border between can-do and mildly psychopathic: "The Apprentice's" wacky Sam Solovey, who fell asleep on the job and tried selling a cup of lemonade for $1,000, and its manipulative, dishonest -- and riveting -- Omarosa Manigault-Stallworth. Rob LaPlante, who casts "The Apprentice" (and who got his start working for Alpert), considers Omarosa his greatest casting feat to date. Even rival Mike Darnell, the reality TV czar at Fox, concedes: "Omarosa was one of the best characters in recent memory. I would have kept her on the show longer."

Many of the questions in this vetting process, therefore, are aimed at determining not whether a candidate is too crazy, but whether he's just "crazy" enough. Today, goaded by Alpert, Rob Cieslinski's questioner is needling and provocative, looking for edges -- "Looking at a guy like you, 6-foot-5, I'm surprised you're such a pushover." But Rob is unflappable. "He's a nice guy," Alpert says, "a team player, all-American." Everyone in the room can see the door is closing on Rob's chances. "The passion and energy doesn't come through on the screen," adds Jon Murray, the co-founder of the company. The interview is over: Rob will probably be staying in his job at Hewlett-Packard for some time to come.

Anyone who watches reality TV would conclude that producers enter the casting room with stock characters in mind -- "the Nerd," "the Jock," "the Bitch." The genre's most successful shows, however, won't admit to searching for types. Mark Burnett, the secretive producer of "Survivor" and "The Apprentice," insists he has no perfect mix, no secret casting formula; he merely seeks "a bunch of very A-type, driven people." But the application for "Survivor" explicitly asks candidates to state which character from "Gilligan's Island" they most identify with, and according to Lynn Spillman, who casts "Survivor," Burnett tells her to think in terms of the '70s sitcom as she makes decisions.

John Saade, a former reality TV executive for ABC who has annoyed his peers by writing "The Reality TV Handbook," which attempts to demystify the casting process, says he likes to conceive of each cast as a family. "There's the aging alpha male," he says, "the young alpha male gunning for his position, the crazy uncle sitting off to one side, the hot sister."

When I describe Saade's technique to Mike Darnell, the Fox reality chief, he rolls his eyes, calling that approach "too philosophical for me. I want the crazy bitch, the nice guy, and as much conflict as is humanly possible." Lynn Spillman agrees that pronounced differences are key, and holds to a simple casting mantra: "sex, conflict, humor." Surely, however, the grande dame of reality casting, Sasha Alpert, gatekeeper for Branson's success, wouldn't rely on some cheap formula. "You want to know the truth?" she says, leaning forward at the Bunim/Murray offices, grinning conspiratorially, and a bit sheepishly. "My model is World War II movies -- you know, the hayseed, the urban kid from Brooklyn. This is the opposite of everyone from the same family. It's everyone from a very different family."

Now in line for Alpert's unmerciful scrutinizing is Shad Sharp, another of today's five finalists. A 31-year-old self-described loan shark from Oregon, Shad made his first million at 24 and owns a jet. That success caught producers' notice early, and in his most recent interview he was impressively slimy. "OK, I'm going to go find a human side," Alpert says to the team, as she prepares to conduct Shad's final interview. "Do you have a microscope?"

From early on, Shad annoys her. He makes a habit of flashing a toothy grin at the least appropriate times, like when being asked about cheating on his girlfriend or screwing people over in business. "How come you smile after every question?" Alpert asks. "Did you read it in a book?"

No, Shad says, all gums.

"Do you smile when you're firing someone?" Alpert asks.

"I don't know," Shad says, lamely. "I'm a happy person."

Alpert's interview doesn't reveal much more depth, and the consensus in the room is that they've broken through to the real Shad. He is closed, emotionally disingenuous, one-dimensional. His answers are short and nondescript. Whatever spark they saw in his prior interviews must have been a pose.

Ah, Shad. As Americans have become more savvy about reality TV, applicants have become students of the genre -- "People come in here almost imagining the music that will be played behind them," Alpert says, making posturing and false intentions one more layer to peel away. The key, says Lynn Spillman, is consistency: "They need to be a bitch on tape, a bitch on their application, a bitch on their answering machine." Alpert and her team see right through Shad, and he becomes the butt of their jokes. They mock his lingo (he describes his girlfriend as "a good gal" and uses "rock 'n' roll" as a verb), his favorite color (silver), the pristine whiteness of his teeth.

"He would be much talked about by the others," Jon Murray admits. Ultimately, though, Shad has run headlong into the reality TV truism that phoniness will out. "I think he is who he is," Murray says. "You either want that character, or you don't."

If Shad makes the cut, he will undergo a final vetting by Fox, during which he'll submit to a battery of psychological tests, including a one-on-one interview. In the genre's frontier days, when the only shows around were "The Real World" and "Road Rules," the process consisted of a letter, a picture, an interview and not much more. Gradually, Bunim/Murray added more filtration, and about six years ago, in an effort to deepen the process, brought in a psychologist for the first time -- not so much to screen for dangerous individuals as to provide another level of insight. "Psychologists have a lot of the qualities you want in a casting director," Alpert says. "Very good listening and interviewing skills."

Psychologists became de rigueur in reality TV only in 2000, when the genre exploded and the networks got into the game. "Survivor" was based on a Swedish program called "Expedition Robinson" filmed in Malaysia in 1997; a 34-year-old Bosnian émigré named Sinisa Savija was the first person voted off, and four weeks after returning home to Sweden he stepped in front of a commuter train. Savija's family has always blamed his suicide on the trauma of the reality TV experience. From the start, "Survivor" producer Mark Burnett took no chances, employing psychologists to evaluate contestants' stability and counsel those voted off.

As embarrassing revelations about cast members have piled up -- "Joe Millionaire's" Sarah Kozar, for example, and her appearance in a few Internet bondage videos -- the rigor of background checks has intensified, so much so that characters who once passed muster might not qualify today.

"It would be interesting to see how Puck would do," says Murray, referring to the notorious "Real World" star.

"I'm not sure he'd pass the psych evaluation," echoes Rob LaPlante. "It's a question mark."

Over time, beyond weeding out fragile or unhinged people, casting directors have made creative use of psychologists' insights, to evaluate personality and foresee narrative arcs. "They'll make predictions like, 'That person will be defensive and has a possibility of closing down," Alpert says.

As valuable as those insights may be, they are made possible by another weapon in the casting director's arsenal: the hectoring interview. Hardball questions pierce veneers, drill down to core personality. They bypass interview anxiety. They jar a person's equilibrium as a shortcut to exposing true self. "How they answer or don't answer can be more relevant than the question itself," Alpert says.

And with Aisha Crump, now on the firing line, it works.

Aisha is described in Bunim/Murray's internal "casting summary" as a "5'2" petite Puerto Rican firecracker." She arrives for her interview in a low-cut, lavender, silk cocktail dress. A 26-year-old pharmaceutical sales rep in Chicago, she totes several broad-brush assets: She's videogenic, offers racial diversity, and seemed in earlier interviews to be opinionated and argumentative. At first, however, the conversation is disappointingly flat. The casting team seems distracted. They talk to each other, come and go from the room, take and make calls. Aisha seems to be losing them.

Sasha Alpert leans into the mike and offers comments intended to rile Aisha. "I don't think you can win; you're too sweet ... People are going to walk all over you. You're never going to win this game."

Aisha rises to the challenge. She tells a story about hiring a contractor to rehab a house. It's a typical contractor nightmare story, told with kindling heat and genuine recollected anger (as well as a keen understanding that a role on "Billionaire" hangs in the balance). "This is good," Alpert says to no one in particular. "Convince me."

Aisha, on fire now, builds to how she threatened the contractor with blackmail, telling him, "I have so much dirt on you." So, Aisha can play rough. She is one with her anger. Now, the casting team is focused, excited. Aisha has shown herself to have a volatility that might combust in prime time.

The interviewer, after finishing with Aisha, joins the rest of the team in the casting room. "So," she says, "I assume people liked her?"

If aggressive questioning unearthed gold in Aisha, it will reveal something less appealing in Stuart Bennett, a 35-year-old Washington consultant whose character is already sketched: gay, mixed-race, ex-drug addict. His father died the day before his first interview with Bunim/Murray; Stuart began crying during the interview, and that rawness impressed the casting team.

Today, at first, they are still liking him. Shown pictures of various leaders and asked for his reactions, he is pithy. George W. Bush? "Comedy." Ken Lay? "Busted!" The casting team laughs. As Alpert's interview progresses, though, he begins to seem complacent.

"How badly would you like to win?" she asks.

"I'd like to win," Stuart says, unconvincingly.

"What are you willing to do?" Alpert begins riding him. "I see you on that tarmac," she says.

When she asks him about George W. Bush, Stuart is dismissive. "You think it's better to get a blow job from an intern?" Alpert asks.

"Everyone's either gotten or given a blow job," Stuart says.

"I've never gotten a blow job," Alpert says.

"Like I said, everyone's either gotten one or given one."

There's an awkward pause. Alpert seems momentarily at a loss for words. In the casting room, everyone cracks up.

Alpert says she's made Stuart angry. He denies it. She insists. Finally, Stuart lets loose: "You want me to get angry? OK ... YOU'RE FUCKING PISSING ME OFF!"

The anger, though delivered on cue, is an explosion, sudden and scary. Everyone's paying attention now. "Do you think you could snap?" a casting consultant hired by Virgin says to the screen. She turns to Jason Horowitz, the supervising casting director, and asks about the "powder-keg" issue. "We let Fox and risk management weigh in," he says.

Risk management, besides a criminal background check and a physical (including testing for sexually transmitted diseases), involves several psych exams, from an IQ test to the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. If someone "loads" high on the psychopathy scale (one piece of the MMPI), or the depression scale, a red flag might go up. If, on the other hand, someone has a few issues, says Richard Levak, a psychologist who consults on "Survivor" and "Apprentice," "but have a big personality, are dying to go, have a big heart ... for many of these people, these shows really do change their life in a positive way."

Stuart, who a few moments ago was amusing, suddenly seems less so. That he first interviewed for the show the day after his father died -- a fact that was previously overlooked because of how impressively "raw" it made him -- is now pointed to as "strange." He further hurts his case when he admits that he's sick of his career and wants to be an actor. Bunim/Murray is after people who genuinely yearn to be Richard Branson's protégé, not people who want to launch a career in show business.

But Stuart's ambition clearly points to the way that reality TV has changed. Winning the game has almost become the consolation prize. The real winners of "Apprentice," surely, are Omarosa and Sam, both of whom are far more memorable than either of the two finalists, smooth runner-up Kwame and bland victor Bill. Bill may have snagged the job with Trump, but as his pretty-boy face recedes, it's Sam we remember, with that menacing death stare he gave Trump upon being fired and his Hail Mary bid on the season finale to pay Trump $250,000 to become his employee. It's Omarosa who we followed when she showed up at the Democratic National Convention in Boston (talking on a cellphone in a no-cellphones-allowed restaurant, of course), who got a police escort when she attended the NAACP convention in Philadelphia, who launched a 900 number where you can chat about her for $3.95 a minute. "They've always been there," Jon Murray says of these new celebrities. "They just haven't been on TV before."

Candida Tolentino, the last interviewee, is a raw foods chef and real-estate investor from an upper-middle-class black family. Sasha Alpert was initially struck by her sense of style (she wears a scarf tied around her neck) and a sweetness that seemed, promisingly, to conceal something more ominous. Candida has already revealed to the casting team that, contrary to what her parents believe, she's not a virgin. While describing her physician father as "a genius," she has also called him "fat," "lazy," "cold," and "kind of crazy." The day before her first interview, she jumped out of an airplane to prove she was up to Branson-style adventure.

In her interview today, she doesn't recognize several of the photographs shown to her (Ken Lay, Steve Jobs and Warren Buffett), but that doesn't bother the casting team. "She's not an MBA type," Murray says. "She's more of an entrepreneur."

When Candida sees Bush's picture, she spits: "Idiotic buffoon! Criminal!" Then she says: "I absolutely think Bush is responsible for the twin towers coming down." The interviewer pushes Candida to back up her conspiracy theory, to no avail.

"She's gorgeous!" says one of the casting team.

"She definitely has a lot of energy," Alpert says.

The interviewer says he supports Bush: "I think he's a strong leader." Candida doesn't bite. He asks about her temper, about being a vegan, about the colonics she receives. She informs the interviewer, a carnivore, that his intestines are "disgusting."

"She's just great," someone says.

"Very intelligent," Alpert adds.

In two days, the casting team will make its picks. Of those, one will reveal a previously undisclosed fact to the Fox psychologist and be bounced from the show (the show's producers will not elaborate on what happened). Rob Cieslinski, the superhero, was too vanilla in the end; other regular-white-guy finalists were funnier or darker. Shad may have been captivating, but no dice. "That's a tough person to have on a reality show," Alpert says, "because they're not being themselves." Stuart Bennett was another disappointment, a passive-aggressive would-be actor rather than a hungry aspiring entrepreneur with his heart on his sleeve. Aisha Crump makes it. And, to nobody's surprise, they like Candida Tolentino.

In her final interview, Candida proves herself ill-informed, hyperbolic, dogmatic and angry. She's also opinionated, stylish and has beautiful skin. Candida is made-for-TV, with an exoskeletal emotional life: No thought or feeling flits across her consciousness that does not also register on her face or in her gestures. She has the golden skill set. The casting team swoons. The interviewer finishes with her and comes into the room. "C'mon," he says, "could it be more obvious?" Candida, too, is in.

Four days into shooting, Sir Richard calls from London. He is taking a day off from the show; as he speaks, the cast -- which includes a former tennis pro who left the circuit to attend Yale and start a successful college business, and a fashion model looking to leave the catwalk behind -- is airborne, headed somewhere on a 13-hour flight. Sir Richard has already left three people on the tarmac. He thinks that roughly two-thirds of the cast are unlikely to be the last man or woman standing: one being 24-year-old virgin Jennifer who thinks Hong Kong is in Japan and has never heard of Capetown. "I have a funny feeling she's not going to become a great entrepreneur," Sir Richard says. He adds, charitably: "Maybe one day."

What about Aisha and Candida? "Candidly?" he asks. Then, choosing his words carefully: "One of them's tough and I suspect would be quite a taskmaster when it comes to staff, and determined." He implies that he's talking about Candida. "The other one's fun, a good little dancer, again determined, slightly more outward going, not necessarily someone who'll go a long way in business."

Sounds like neither will go the distance on the show. But who cares? Either could still become the big winner.

Shares