Adele Mailer, wife of novelist Norman Mailer (1951-1962). Cold and remote

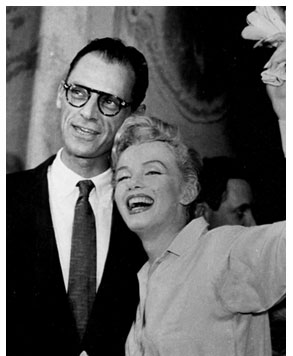

The Millers were pretty secluded [near Bridgeport, Conn., in the mid-1950s]. I don’t think anyone, including the [William] Styrons, were asked to visit. Norman was really pissed that Miller didn’t call to invite us over for a neighborly drink. But then again, why should he? The two had never really liked each other, even in the forties when they were unknown and both had studios in Brooklyn Heights. Norman was writing “The Naked and the Dead” and Miller “Death of a Salesman.” When I first started going out with Norman in 1951, I met Arthur and his first wife at a party given by Norman Rosten, a poet friend of Norman’s. At the time, Miller was rather cold and remote, perhaps a cover for shyness. His wife was a handsome, tall, blonde, matronly looking woman. Miller showed no animosity, just a coolness toward Norman.

From “The Last Party: Scenes From My Life With Norman Mailer,” by Adele Mailer (Barricade Books, 1997)

Ronald Radosh, journalist and historian. His “whole loaf”

[At] Elisabeth Irwin, the high school affiliated with the Greenwich Village elementary school known as the Little Red Schoolhouse … our class’s choice of [black intellectual W.E.B.] Du Bois as our graduation speaker created a mini-crisis for the school … The school’s leadership worried that the choice of Du Bois [a pro-Communist leftist] as the official commencement speaker — this was the class of 1955, after all — could put EI under … [The principal] told us to choose another speaker …

Our fallback choice for commencement speaker was Arthur Miller, whose play “The Crucible,” about witch hunts in colonial Salem, was a parable on McCarthyism. Miller’s left-wing credentials were impeccable. In his speech he told us never to accept “half a loaf.” We took that to mean that we should have demanded that Du Bois speak, and that the school’s authorities were wrong to capitulate to pressure from objecting parents. But a short time later, we learned what Miller must really have been thinking about. As the whole world was soon to know, he left his wife, a simple social worker, for America’s leading Hollywood beauty queen, the incomparable Marilyn Monroe — “the whole loaf” incarnate. (New York)

From “Commies: A Journey Through the Old Left, the New Left and the Leftover Left,” by Ronald Radosh (Encounter Books, 2001)

Simone Signoret, actor. Warm and handsome

One day … the world’s most famous newly-wed appeared at the Rue Francoeur. Arthur Miller has finally come to meet the Proctors [characters in “The Crucible”]. He found them not at all gay. He wasn’t gay, either. The American left-wing intellectuals had no reason for being joyful then [the height of McCarthyism]. We were meeting for the first time, and yet it was as though we already knew each other. By then we had been living with characters of his invention for two years, so he, [Yves] Montand and I already knew each other well. He may not have been gay, but he was warm and handsome and he spent the day with us and then went back to London to Marilyn [Monroe], whom he promised to bring to see us (Paris, 1956)

From “Nostalgia Isn’t What It Used to Be,” by Simone Signoret (Harper & Row, 1978)

Al Waxman, actor. Private performance

The St. Mark’s Playhouse … a private performance of “A View from the Bridge” for a limited and select audience … The actors had been denied the rights to do “A View from the Bridge” in New York, even off-Broadway, because it had been done on Broadway only a year or two earlier … These actors and their director prevailed upon Miller and his agent to let them audition, as it were. They spent a month rehearsing just to give one private performance for Miller and his agent …

The St. Mark’s is a small theatre at Second Avenue and Eighth Street. No matter where you sat, you would be near Miller. Anticipation. He was the last to come in. As we all waited, we wondered if he would bring Marilyn Monroe. Alas no, it was just his agent accompanying him. Still, they were like royalty. Everyone in those days was a little dressier than today, even at an off-Broadway house. The men all wore shirts, ties and jackets, despite the stifling, airless heat of the humid late-spring evening. No one loosened a tie or removed a jacket until they saw Miller do so.

The play started. For me, it will always be one of the most memorable nights in the theatre. Not only were the actors and the production phenomenal, but within earshot and within view — he was taller than everyone else — were Miller’s reactions. It was as though with one eye I watched the stunning production and my other the impact the production was having on Miller. He was shaking his head slowly from side to side in awe and appreciation of the work before his eyes, and quietly but audibly saying over and over, “Amazing!” (New York, 1958)

From “That’s What I Am,” by Al Waxman (Malcolm Lester Books, 1999)

John Updike, novelist and critic. Glad to be an American

To the Soviet Union [in 1964] for a month as part of a cultural exchange program …

I came way from that month … with a hardened antipathy to communism …

There was something bullying egocentric about my admirable Soviet friends, a preoccupation with their own tortured situations that shut out all light from beyond. They were like residents of a planet so heavy that even their gazes were sucked back into its dark center. Arthur Miller, no reactionary, said it best when, a few years later, he and I and some other Americans riding the cultural-exchange bandwagon had entertained, in New York or Connecticut, several visiting Soviet colleagues. The encounter was handsomely catered, the dialogue loud and lively, the will toward friendship was earnest and in its way intoxicating, but upon our ebullient guests’ departure Miller looked at me and said sighingly, “Jesus, don’t they make you glad you’re an American?”

From “Self-Consciousness: Memoirs,” by John Updike (Alfred A. Knopf, 1989)

John Corry, journalist. Rabbinical

I was pleased by my new circle. A Times reporter might walk with captains and kings, but he knew he walked with them only because he worked for a powerful institution. Harper’s was an institution, although it was not nearly so grand, and you thought you could walk on your own. I went about and met lions … The playwright Arthur Miller was a rabbinical presence. You expected him to offer a blessing. (New York, late 1960s)

From “My Times: Adventures in the News Trade,” by John Corry (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1993)

Billy Crystal, comedian. Making people cry

When I auditioned unsuccessfully, for “Death of a Salesman” with Dustin Hoffman, I met Arthur Miller and got him to autograph a copy of the play for me. He told me that he was fascinated by stand-up comedy and that his earliest writing, in fact, had been a pair of humorous monologues for himself. Miller said he learned quickly, however, that he was better at making people cry than laugh.

And all I kept thinking, standing with this brilliant man, was: This guy slept with Marilyn Monroe. (New York, late 1970s)

From “Absolutely Mahvelous,” by Billy Crystal with Dick Schaap (G.P. Putnam’s, 1986)

Andy Warhol, pop artist. “Rich-kind-of-Jewish look”

Arthur Miller was at the screening [of “The Deer Hunter”]. It was interesting to see him. He’s very good-looking. I guess people like that work at it, the rich-kind-of-Jewish look … Arthur Miller looked refined, and a straighter face than Richard Avedon, but like that. Like a Lehman. I guess they marry good-looking wives and get good-looking children. (New York, 1978)

From “Diaries,” by Andy Warhol (Warner Books, 1989)

Alfred Kazin, literary critic. At the dump

Arthur Miller and I came upon each other in the Roxbury [Connecticut] dump on Sunday morning. The setting was more for a Beckett play than for one by Arthur Miller — hills of garbage, of exhausted and now-despised American commodities recurrently ground down, smoothed out, and buried by a tractor …

Miller stands there, tall and raspy, with his usual assured sense of himself, dressed as always in a blue work shirt, work pants, and heavy work shoes. Arthur is a millionaire, has an estate, travels everywhere with the greatest freedom and aplomb, is a steadfast pillar of the American stage and the American scene. So he always comes on straight and strong in that blue work shirt, as a worker should — and opens up every conversation, at least with me, by expressing his bitterness at the Times, which has only one drama critic, whom Arthur blames for his recent lack of acclaim on Broadway …

We are all intensely personal about life and art and with each other. Arthur’s way of being personal is to discourse on the many ruses and snares of power in America. I find him fascinating on this subject and valuable, one of the few radicals out of the thirties who has never lost suspicion of American society. He certainly knows his social evidence. (1980s)

From “A Lifetime Burning in Every Moment,” by Alfred Kazin (HarperCollins, 1996)

Sara Nelson, editor and literary journalist. Two thoughts

I was introduced to Arthur Miller. Looking into the face of the creator of “Death of a Salesman,” I could think only two thoughts: (1) Great play! And (2) What was Marilyn Monroe really like? (New York, 1990s)

From “So Many Books, So Little Time: A Year of Passionate Reading,” by Sara Nelson (G.P. Putnam’s, 2003)