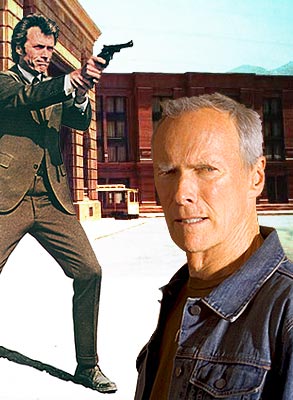

Clint Eastwood is sorry. Sorry about those extras he shot dead in the Spanish desert for an Italian director. Sorry that Dirty Harry Callahan embodied the idea that we should just Kill All the Bad People. Even sorry for all the people he punched in the face while his ape buddy Clyde stood on the sidelines, raising the roof.

Or so it seems. Eastwood’s latest film, “Million Dollar Baby,” is a decent bet to win him Oscars for best picture and best director this Sunday. But it’s hard to shake the sense that the film, with its somber, unsparing portrayal of injury and suffering, is another in a series of efforts by Eastwood to make amends for his early career, when he became famous as the vengeful loner, the angel of violent retribution, the Man with a Gun. It’s an interpretation that Eastwood himself dismisses — “I’m not that haunted by my past,” he recently told Entertainment Weekly — but one increasingly common both among his (predominantly liberal) admirers in film criticism and his growing number of conservative detractors.

Eastwood is the rare artist who has gone from being condemned as a fascist propagandist by the left to being condemned as a fascist propagandist by the right. The former charge was leveled in 1971, when the New Yorker’s Pauline Kael described “Dirty Harry” as “fascist medievalism”; the latter, earlier this month, when Ted Baehr, the head of the Christian Film and Television Commission, declared “Million Dollar Baby” to be a “neo-Nazi movie.” The particulars of the accusations have little in common: Kael was objecting to “Dirty Harry’s” enthusiasm for vigilante justice, Baehr to “Million Dollar Baby’s” perceived support of euthanasia. But the two critiques are illustrative of the journey Eastwood has taken over the last 34 years, from conservative icon disparaged by much of the critical establishment to Hollywood statesman (and Academy favorite) widely vilified on the right.

The broad contours of this evolution are widely known: Eastwood’s fluke debut as an international star when Italian director Sergio Leone plucked him from a $700-per-episode stint on TV’s “Rawhide” for the revisionist western “Fistful of Dollars” and its sequels; his emergence in the 1970s and 1980s as a full-blown film icon, thanks to the “Dirty Harry” movies and a variety of other films in which he alternated between the roles of law-unto-himself gunfighter and law-unto-himself cop; and his dramatic transformation, beginning with 1991’s “Unforgiven,” into a critically acclaimed director of haunting, jaded films about the cost of violence both to its victims and its perpetrators.

Perhaps the clearest summary of Eastwood’s shifting political appeal can be found in two essays by conservative film critic Richard Grenier in the magazine Commentary. The first, published in 1984 and titled “The World’s Favorite Movie Star,” praised Eastwood lavishly for lacking “the slightest doubt as to the legitimacy of the use of force in the service of justice, even rudimentary justice. This attitude has earned him, among some movie reviewers, a reaction I think it is only fair to call hatred.”

But a decade later the tables had turned, leading Grenier to rebuke the star in a second essay, titled “Clint Eastwood Goes PC.” In it, he noted his former praise for Eastwood and for “the role he [had] played throughout his career: the enforcer of law and justice,” before continuing, “But now all has changed. Today Eastwood is the darling of the critics. [He] has been on a spiritual voyage and is now reaping the rewards.” This analysis was based largely on “Unforgiven,” which Grenier described as “a full-scale, systematic act of contrition, a repudiation and dismantling of the whole legendary, masculine character type of which, for this generation, Eastwood himself had become the leading icon.” Though Grenier’s analysis may be more explicitly political than that of most other critics, his view that Eastwood’s latter films have been an apology for his earlier ones has become a common one, particularly in the wake of Eastwood’s last two films, “Mystic River” and “Million Dollar Baby.”

But while it’s true that Eastwood’s work, as an actor and especially as a director, has espoused a vague political philosophy — and one that has evolved over time — it has never been nearly as programmatic as either his admirers or his detractors imagine. The films he made early in his career were never as “conservative” as their reputation, and even his most prominent revisionist works — “Unforgiven,” “Mystic River” and “Million Dollar Baby” — are not as “liberal” as theirs. Both the fascist medievalist of the 1970s and the neo-Nazi eugenicist of today have been largely the projections of his accusers’ own political nightmares.

There are any number of examples of liberal undercurrents embedded in Eastwood’s early work: the futility-of-war subtheme of “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”; Josey Wales’ decision to forgo his (eminently justified) vengeance against the man who betrayed him to the Union in “The Outlaw Josey Wales”; the gender education imparted to Eastwood chauvinists by strong women in “The Enforcer,” “The Gauntlet,” “Tightrope,” etc. But no early film was as explicit a subversion of Eastwood’s vigilante image as “Dirty Harry’s” 1973 sequel, “Magnum Force.”

The film opens with the acquittal, on grounds of inadmissible evidence, of a San Francisco labor boss suspected of murdering a union reformer and his family. (The family is important, as a consistent Eastwood theme is the particular evil of those who harm women or children.) On his way home from the courthouse, the labor boss is killed. This is followed by the executions of several other top crime figures, including a pimp whom we’ve watched kill one of his girls by pouring drain cleaner down her throat. The killings, it turns out, are being committed by a squad of renegade cops on the force, cool, good-looking hotshots (among them a pre-“Hutch” David Soul, pre-“Otter” Tim Matheson and pre-Dan Tanna Robert Urich) not unlike younger versions of Eastwood himself. Unsurprisingly, they invite Harry to join them in their campaign to rid the streets of scum. Somewhat more surprisingly, he declines. (“Apparently you’ve misjudged me,” Eastwood tells Soul, in a line perhaps intended equally for his liberal critics.) In the end, he is forced to kill his young imitators, along with the superior (played by Hal Holbrook) who had been working with them.

Why is “Magnum Force,” with its explicit rebuke of vigilantism, so rarely cited as a film in which Eastwood began the deconstruction of his vigilante icon? One reason is that in subsequent films (including the remaining “Dirty Harry” sequels) Eastwood reverted to his vengeful, outside-the-law persona with little obvious alteration. But another likely factor is the feel of “Magnum Force.” In art as in politics — and certainly where the two intersect — our responses are often more attitudinal than philosophical. We respond to the tone and then interpret the underlying facts in a way that will be consistent with that initial reaction. And while the moral of “Magnum Force” may have been in clear and deliberate opposition to that of “Dirty Harry,” the atmospherics weren’t all that different. Once again, Clint is alone in the department. (No matter that this time it’s because his boss and fellow officers are fanatical vigilantes rather than criminal-coddling bureaucrats.) Once again, it ultimately comes down to him, the Good Man against the Bad Men, with no time for mercy or cowardice or playing by the rules.

Further evidence that Eastwood’s reputation as “the enforcer of law and justice” was as much a product of his movies’ attitude as of their politics can be found in the 1978 ape-buddy flick “Every Which Way but Loose.” Though hardly a “serious” film, it was Eastwood’s most successful movie till then, raking in an astounding $85 million. Eastwood plays Philo Beddoe, a bare-knuckles brawler who wears a cowboy hat, drives an old pickup, and listens to country music. Although most of the movie is devoted to his disputes with two cops and a biker gang, his real cultural foil is a snooty USC student who’s onscreen for less than two minutes early in the film — just long enough for her to describe the country-western mentality as “somewhere between moron and dull normal” and then be cut down to size by Beddoe. In one of the most successful examples of pre-“Passion of the Christ” politico-cultural marketing, the film’s distribution specifically targeted rural and small-town theaters in the South and West.

Once you get past the conservative cultural trappings, however, “Every Which Way but Loose” has nothing at all to do with meting out justice, upholding the law, or any of the other political tropes that were thrown Eastwood’s way at the time. Beddoe may be charming (and, like Eastwood himself, fond of animals), but he is essentially a miscreant — an unproductive member of society who picks fights constantly and very nearly at random, and almost always throws the first punch. Indeed, the reason for his ongoing difficulties with the two policemen is that he assaulted them in a bar without provocation. Had Beddoe been played by Jack Nicholson or Dennis Hopper, he would doubtless have been seen as exactly the kind of anarchistic free spirit that liberal audiences applauded and conservative ones reviled.

The dramatic reevaluation of Eastwood’s work over the last decade has similarly been driven at least as much by tone as by content. Take “Unforgiven,” the film in which Eastwood is generally considered to have fundamentally altered his approach to violence. If “Magnum Force” represented a radically different story told in a style similar to that of his previous ones, “Unforgiven” was just the opposite: a familiar storyline about a relentless avenger told in a different key, more tragic than heroic. Eastwood’s character, Will Munny, is a formerly heartless killer domesticated by the love of a good woman who has since passed away. In an effort to raise money for his two young children, he accepts a lucrative commission to kill two cowboys who had cut up the face of a prostitute. After he and his two partners (an old friend played by Morgan Freeman and a boastful youngster played by Jaimz Woolvett) arrive in the town where the job is to take place, Eastwood endures life-threatening illness, a savage beating by the town sheriff (Gene Hackman), and his partners’ discovery that they lack the stomach for killing. After his commission is completed, Eastwood learns that Freeman was caught on his way home and beaten to death by Hackman, and he wreaks a bloody vengeance on the town, killing the sheriff and several other men before mounting his horse and riding off.

As David Edelstein noted in a smart 2003 article in the New York Times, the concluding bloodbath makes “Unforgiven” at best an ambivalently anti-vigilantism film. (Indeed, the film’s last spoken line is Eastwood threatening the townsfolk, “You better bury [Freeman] right. You better not cut up nor otherwise harm no whores. Or I’ll come back and kill every one of you sons of bitches.”) Yes, it’s clear Eastwood knows that on some level what he has done is wrong, and that it will haunt him the way his earlier killings haunted him throughout the film. But his life goes on, and apparently not too unhappily — a postscript informs us that he’s rumored to have taken his children to San Francisco and prospered there. Moreover, Eastwood’s retribution isn’t presented as unambiguously evil. Freeman was a decent, gentle man and Hackman a sadistic monster. Finally, the lethal, commanding avenger that Eastwood has become by the film’s end is a vastly more imposing figure than the clumsy, tentative farmer he is at the beginning. In killing, he has rediscovered his true self. Was “Unforgiven” a deliberate subversion of Eastwood’s vigilante persona? Of course. But a “full-scale, systematic act of contrition, a repudiation and dismantling of the whole legendary, masculine character type,” as Grenier said? Hardly.

Eastwood went further with 2003’s “Mystic River,” tackling the question of certainty: Even if a crime has been committed that merits death, what happens if you kill the wrong person? (His mediocre 1999 capital-punishment film “True Crime” could be seen as a dry run for this subject.) “Mystic River” concerns three friends, played by Sean Penn, Tim Robbins and Kevin Bacon. As a boy, Robbins was abducted by pedophiles, who kept him for several days before he managed to escape; as an adult, he is “damaged goods,” shambling through life like a zombie. Penn, meanwhile, is a tough ex-con who owns a grocery store; Bacon, a cop.

One night, Penn’s beautiful teenage daughter is brutally murdered; that same night, Robbins comes home covered with blood, which he explains away with a series of shifting stories. Believing that Robbins killed his daughter, Penn ultimately executes him. But Robbins was not the daughter’s killer, and Penn must come to terms with the fact that he has killed not only a friend but also an innocent man. As with Will Munny in “Unforgiven,” it’s clear that this fatal error will weigh on Penn’s conscience in the years to come, though again it’s not entirely clear how heavily. Like Munny, Penn seems to have recovered a source of personal strength in his willingness to avenge — even wrongly — those he loves. (Penn’s wife, played by Laura Linney, certainly feels this way, telling him, “You’re a king. And a king knows what to do and does it, even when it’s hard.”)

Penn’s ambivalent response to the discovery that he has killed an innocent man is not the only way in which “Mystic River” deviates from a simple, anti-vigilantism message. The greater, though largely unexamined, issue is that Robbins is not completely “innocent.” While he may not have killed Penn’s daughter that night, he did commit murder: The blood on his shirt came from a pedophile whom he encountered in the street and beat to death. That murder is almost an afterthought in the film, however, a necessary plot device that is given remarkably little moral weight. It’s as if Eastwood is telling us that the killing of a pedophile doesn’t count. (And that’s if Robbins’ victim even is a pedophile: We get only a glimpse of the boy who is with him, but he is clearly well into his teens and could easily be of age.) “Mystic River” may be a melancholy meditation on the self-perpetuating cycle of violence. But, like “Unforgiven” before it, it’s far from an unequivocal condemnation of vigilante justice.

“Million Dollar Baby” seems to renounce retribution altogether, though it does so quietly. The film differs in subject matter from most of Eastwood’s work — there are no cops or criminals or cowboys — but in the end, it too is a film about the human cost of violence. (If you are still unaware of the film’s central plot twist, and you want to remain that way, stop reading now.)

Maggie Fitzgerald (Hilary Swank) is a 33-year-old waitress who’s dreamed of becoming a boxer. She persuades a grizzled old trainer named Frankie Dunn (Eastwood) to take her on, and he turns her into a top fighter. When Swank gets her shot at a title fight, however, the triumphal sports movie takes an unexpected swerve: Hit by a dirty shot after the bell, Swank is permanently paralyzed from the neck down. Without hope of recovery, she attempts suicide before finally persuading Eastwood to help her die.

To some degree, “Million Dollar Baby” is still locked in Eastwood’s Manichaean world of good guys and bad guys: The boxer who cripples Swank is cartoonishly villainous, a former East German prostitute who is famously “the dirtiest boxer in the ring” and who deliberately hits Swank from behind long after the round has ended. But while Eastwood’s invocation of big-E “evil” is all too familiar, what’s new is that he shows no interest whatsoever in punishing that evil. No one jumps into the ring to attack the dirty fighter, or even takes the case up with the boxing commission. Having fulfilled her role, the villain vanishes from the movie. Back in the “Dirty Harry” days, Eastwood explained that his movies were about the rights of victims rather than the rights of criminals. But he rarely wasted much screen time on those victims; their stories of loss were little more than the rationale for his stories of vengeance. In his more recent films, such as “True Crime,” “Blood Work” and “Mystic River,” Eastwood has devoted more time to the suffering of the victims. With “Million Dollar Baby,” he focuses exclusively on it, essentially letting the perp walk. His character is a would-be healer, not a would-be avenger.

But Swank cannot be healed, and Eastwood eventually grants her plea to end her life. This has been read as a pro-euthanasia message in some quarters, but here again, the reality is somewhat more complicated. Eastwood’s boxing trainer, Frankie Dunn, is in many ways another iteration of Will Munny from “Unforgiven” (and, for that matter, of Sean Penn’s character in “Mystic River”). Like Munny, Dunn is filled with remorse for some past crime, though we never learn what it is, only that it has to do with a daughter who sends his letters back unopened. Like Munny, at the end of the film he contemplates an act that he knows will result in his being lost forever, with no hope of salvation. And like Munny, he moves away after committing the act, leaving behind his friends and disappearing into the realm of rumor (in this case, the rumor of a swampland diner rather than of the City by the Bay). The parallel is not exact, but it is striking. Yet the two films have been read in diametrically opposite ways: “Unforgiven” as a condemnation of Munny’s vengeance killing and “Million Dollar Baby” as an endorsement of Dunn’s mercy killing.

Both films, in other words, have been generally interpreted as having a “liberal” message, much as Eastwood’s films in the 1970s and 1980s were widely read as “conservative” even when they condemned war (“The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”), denounced vigilantism (“Magnum Force”), disdained law and order (“Every Which Way but Loose”), or concluded on a note of forgiveness (“The Outlaw Josey Wales”). Do Eastwood’s recent films constitute an apology for his earlier ones? Perhaps. But he may not be the only one with apologies to make.