With his 12th novel, “Saturday,” Ian McEwan has reached a position that most writers dream of and few ever attain: His books are both automatic bestsellers and critically revered. There’s no formula at work here. “Saturday” is about as different from his 2001 bestseller, “Atonement,” as you can imagine. Instead of a twisty, self-devouring meditation on lies, guilt and literature, “Saturday” is a smooth, seamless creation depicting one day in the life of Henry Perowne, neurosurgeon, Londoner and happy man. And where “Atonement’s” narrator Briony Tallis is a published author, Perowne not only doesn’t write books, he can barely bring himself to read them, though he tries for the sake of his daughter Daisy, a poet about to publish her first volume of verse.

On his way to a squash game, and anticipating a family dinner party that will bring Daisy back home after a few months abroad, Perowne gets into a fender bender with a petty hoodlum in whom he recognizes the early signs of a degenerative nerve disease. He uses his expertise to escape a confrontation, but the incident hangs over the rest of his day — playing squash, visiting his elderly mother, listening to his son play in a blues band, whipping up a seafood stew — and results in a terrifying intrusion into his contented life. Literature winds up playing a surprisingly important role in that crisis, but so does the work that brings Perowne, a confirmed atheist and lover of the material world, so much satisfaction. All this takes place against the backdrop of the buildup to the Iraq war in 2003. In fact, it’s the international protest march against the coming war that leads to Perowne’s accident, and at one point he argues bitterly with Daisy about whether or not the invasion is a good idea.

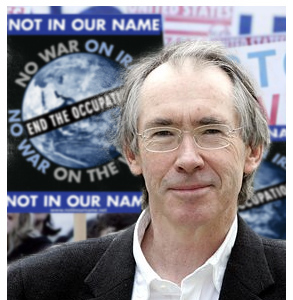

Despite Perowne’s indifference to literature, he’s one of McEwan’s most autobiographical characters yet. One of the many things they share is a complicated attitude toward the invasion of Iraq. During his recent book tour through an America in the throes of the Terri Schiavo debate, McEwan met with Salon to talk over our confusion of public and private life, his ambivalence about the war, whether the contemporary novel and magic realism are worth reading, and why he hates the slogan “Not in Our Name.”

What was the genesis of this novel?

No single nugget, really. A vague desire, an old wish, having written a historical novel, to write a novel not only about the present but very much in the present. That was even before 9/11 had happened. I knew I wanted to be back at the beginning of this century, rather than in 1935. I moved to central London after living in Oxford for 17 years. I thought I’d very much like to write a London novel.

I’d also formed an ambition to write about work. I thought whoever my next central character will be, he’s going to damn well have a job. Too many characters in literary fiction mope around and don’t have any job. For very good reasons. Or, they’re college professors, especially in America. This part of London I arrived in is very much a medical area. There are big hospitals here. So already I was beginning to think he’d be a neurosurgeon.

Concurrent with that, 9/11 happened and that was about the time I was publishing “Atonement.” I did think that inevitably if I decided to write about the present, whatever changes the world was going through would percolate into this novel. But I did nothing for a year. I didn’t start until 18 months afterwards.

A lot of people have said they found it impossible to write after the attacks.

I wrote some journalism about it. I wrote two pieces for the Guardian, one while it was still happening.

You mean on Sept. 11?

The Guardian wanted a piece maybe two hours into it. I’d already decided that the phone was bound to ring and I was going to say no, but my mouth said yes. Sometimes it seems that Descartes was right, the mind and the body are separate. It’s horrible to say this because there was this horrible, vile event, but there’s this other reptilian brain that goes into a mode that thinks, I can turn in 1,200 words in an hour. It’s a rush to get it in. Then of course I hadn’t fully taken in what had happened. You can read it on my Web site.

But it took you a while to bring the attacks into your fiction?

I had been planning a little novella about a tabloid journalist. I’d mapped that out and written notes and was pondering. That just seemed irrelevant. Then I did what a lot of people did and became a news junkie and read books about Islam. Talked about it, listened about it and was completely fixated on what we were doing and what we were about to do and what it meant and whose fault it was. I couldn’t get my hands on enough to read about that stuff. I did no writing for about a year, just read.

Slowly I began to think, if I’m writing this London novel and it’s in the present and about the present, then it needs to be about what was going on. And what was going on was the post-invasion of Afghanistan and the lead-up to the invasion of Iraq. And a colossal nervousness after the Bali bombing and even before Madrid. A general sense in European cities, and I guess in the U.S. too, about when the next shoe would drop. We were assured that it was inevitable and I know they were covering their backsides by saying it, but still, it got into the small print of private life.

I began to think, well, we’re now living in horribly interesting times. There are great, grinding sounds of shifting axes of power and interest and alignment and politics and alliances and differences between nations. But also, more interestingly, at the private level, the kind of Edwardian summer of the ’90s seemed like a long party, the post-Cold War, that was over.

I take some interest in environmental affairs and it just seemed we were dancing while the ship was sinking. We had so much opportunity, without major wars to fight, with some money saved that would otherwise go to an arms race, and with economies growing … Anyway, that hadn’t happened. The West just enriched itself. Anti-globalization had yet to concentrate minds on the unfairness of world trade groups, at least in the mainstream. So that was over, that party. There was a hangover feeling as well as the fear factor. All of that fed in to this novel.

And Perowne’s house and neighborhood are also yours.

Most of the novel is fiction, an entire invention, but I decided to use whatever was to hand. I used my own house and circumstances. I turned my son into a guitarist, but that character, Theo, is very much like my son, very gentle. The dying mother is my mother.

That’s unusual for you, isn’t it?

Yes, entirely. For some writers it’s quite standard.

How did if feel to be writing something with that level of autobiography in it?

I don’t know if I’d do it again, but it helped with this material. I decided that if it was going to be of the times and in the present, I’d not invent everything. But, of course, in describing it you shave it away and invent and change reality to suit the rest of the novel anyway.

Perowne has an empirical, material view of life. He’s a man of science in a very comprehensive sense of the term. And he doesn’t get much out of art.

Well, not out of literature.

That’s true. He is moved by music. Was making him that sort of person a choice you made late in writing the novel?

Oh no, he was that from the very beginning. I thought I’d have a go at challenging the notion that happiness “writes white.” That we’re drawn to forms of misery and conflict because they’re easier to describe, while happiness is bland. There’s supposed to be a universality to happiness while there’s a distinctly individual quality about misery. I thought, if I’m going to write about an anxious world, it would be more interesting to put a very happy man into it. Instead of a guy who’s riven by domestic anxieties and teenage kids who are taking far too many drugs and can’t speak properly and a vicious wife, with loathsome …

Let the record show that you’re saying all that with great relish.

Yes, hey, I’m getting a good idea here! But it seemed more interesting if you’re going to have a background of anxiety and bafflement, why not braid it with a degree of domestic contentment? So I decided to give him pleasures and those pleasures were going to be superficial ones like wine and sport, and profound ones like love and sex. To make him free, as it were, to worry about the world. He doesn’t have to worry about his wife and children. Of course, he has a dying mother, but everyone has a dying mother unless they predecease their parents. It was a desire to braid together private happiness and public anxiety.

Also, I found, and this is somewhat paradoxical, I hadn’t meant to write a commercially successful novel with “Atonement.” I was astonished it sold as many copies as it did. So I made sure I was going to write a meditative, digressive novel. I’m free not to write another book that loads of people want to read.

So you felt liberated by not having to write something commercial?

But I’ve never worried about that.

No one would ever call “Atonement” a deliberately or obviously commercial book.

It just turned out to have sold lots of copies. As now, has “Saturday.”

There’s nothing you can do to stop it.

No, nothing I can do. Except maybe to attempt a commercial book. That would probably screw things up.

Both books have a questioning of literature in them, “Atonement” in a way that’s fundamental to the novel, but with Perowne you have someone who’s simply immune to literature.

He plugs his way through his daughter’s reading list. It’s much more playful, but you’re right it’s a continuation. Briony Tallis [in “Atonement”] was obsessive about literature. As Perowne’s character was emerging, it seemed like it would be nice to have someone who really has to force his way through “Anna Karenina.”

One of the privileges of writing novels is to give characters views that you have fleetingly but that are too irresponsible for you ever to defend. You can give them to a character. His views on magical realism, I could never really … I know there are some great novels in that vein. But still, I do have a streak of skepticism about it. So Henry Perowne could work this up for me on my behalf.

It also seems logical that a man who takes the material view of life would want the laws of physics respected in his novels. He wouldn’t want characters just flying out of the room. I do think that the whole “Hundred Years of Solitude” succession of novels became tiresome.

Sometimes we don’t have an affinity for certain literary modes. You might admire the peaks of it but not the foothills.

I’ve always had the sneaking suspicion that once you lift all the constraints and can do anything, as Perowne says, nothing you do really matters. If you don’t have the constraints of the material world, if people can turn into a ketchup pot while you’re talking to them, then what matters? Also, I think you lose psychological plausibility. But, obviously, “The Tin Drum” is a great novel, and “One Hundred Years of Solitude” is a fairly great one. I have higher standards for books like that.

What was it like to imagine yourself into the psyche of someone for whom novels, what you yourself write, are irrelevant? Was that a difficult leap?

No, not at all, it was sort of fun. Because whatever he says about literature, he’s doomed to remain a character in a novel by me. There’s no escape.

So his thoughts on literature don’t come from some dark moment of the soul on your part, where you were lying in bed at night thinking, “What am I doing with my life?”

Actually, good point. During that year I was just describing after 9/11, I did have a period where I didn’t want to read anything invented. I had a Gradgrindian sense that I didn’t want these airy-fairy, wispy inventions. It was a passing mood. The times were too interesting for the novel, that was the sense. With my stash of remaining years shortening, I want to be seriously informed about the world. If I’m going to read about invented characters they’ve got to be really … In some ways it might be better to forget the contemporary novel altogether. If you haven’t already read “The Charterhouse of Parma” or “The Secret Agent” or “The Brothers Karamazov” or “Middlemarch,” why not be reading those?

In other words, contemporary novelists do have a great burden laid upon them, which is what Henry James said the novelist’s first duty is: to be interesting. Otherwise, why turn away from the shelf of nonfiction in our massive local bookstore, which is groaning with interesting books? I just read a book about the last 150 years of the Roman Republic about which I knew absolutely nothing. I read in awe and gratitude that someone had laid out all this information for me.

I like to feel that novelists are seriously dedicated to their art, which means doing a lot of reading and thinking about the novel. Sometimes it seems like writing novels has become a contemporary form of expression, expression of self. Much like being a Renaissance gentleman writing a sonnet. It’s seen as a thing that anyone with a reasonable amount of education can do, and it’s your duty as a citizen to write a half-dozen novels.

Do you think a lot of people see it that way?

Yes, I think self-hood, expression of the self, me, is what it’s about. Now, when you’re reading a master, when you’re reading James, you do feel you’re in the hands of someone who’s given his life to this, and a colossal intelligence, and a highly informed intelligence. That’s true of Conrad, too.

I read a lot of the beginnings of contemporary novels. I get sent hundreds of them. I always read the first 10 or 20 pages. Well, sometimes not 10, sometimes one and a half. It’s rare that I feel that sense of being in good hands. It’s almost impossible to find.

Did the Iraq war move in as a background while you were writing “Saturday”?

Yes, it took over. When I was planning, it was just a given. I abandoned myself to the idea that history would be supplying whatever was going on in the novel.

It was only when I’d written maybe 5,000 or 10,000 words, early in 2003, that the big march happened, and I suddenly saw that I could get everything into a day. Otherwise I was going to be locked into accounts of endless comings and goings at the U.N. and the perfidy of de Villepin and the unconvincing Colin Powell. In retrospect, now it all looks incredibly pointless and bureaucratic because you know where it’s all going. Endless newspaper headlines about each tiny twist along the way. I was already despairing of that.

Perowne and his daughter Daisy have a heated argument about the war. He’s friends with an Iraqi doctor who was tortured by the Saddam Hussein regime and he thinks the invasion might do some good. She agrees with the marchers. Did you write that conversation in the heat of the moment, or later?

No, by the time I wrote that, Iraq had been long invaded. I had to work very hard not to allow myself an inch of awareness from after the event.

So you wound up writing a historical novel after all?

Yes! It was only months before, but yeah. I allowed myself one bit of slyness. Right at the end of the row they make a bet about what the outcome of the invasion will be. I already knew they were both right. Perowne predicts that there will be 200 papers free to publish in Iraq, and there are. And, as Daisy predicted, the occupation is a bloody mess. It would be perfectly possible for Perowne to voice much the same argument now, saying you have to salute the bravery of the Shiite community in voting and their tolerance in writing the Sunnis into the government, and we now see the true, brutal face of the insurgency. And Daisy would say, but there are 100,000 people dead and how can you possibly justify that? It’s not settled.

Do you still feel as ambivalent about the war?

Well, it sounds pathetic, but I rather do. We can’t know what would have happened if we’d left Saddam in place. He might have just exhausted himself as a tyrant or, worst case, his horrible sons were ready to take over. He could have lived another 15 years and gotten nastier and more paranoid with age.

Some of the antiwar arguments have been exploded. If the U.S. only wanted lots of oil, think of the oil futures it could have bought for the price of invading Iraq. All the world’s oil for the next 50 years for the $280 billion spent. But I do think the body count is a very dark side of the argument. So yes, sometimes I’m impressed and sometimes I’m just irritated by people who know their minds completely about this. I’m glad I’m a novelist.

In Britain, though, people really expect novelists to have public opinions on that sort of thing.

Yes, ever since a pamphlet came out called “Novelists Take Sides.” Every time there’s some shoot-up somewhere, someone writes to you, and then the novelists all send in something that says, “This despicable, etc.” What’s it all about? It’s certainly not about the Iraqi people.

You feel there’s some other motive?

Oh, I don’t want to impugn very interested people who knew their minds and spoke it, but it’s a bit like Hollywood actresses saying things. What’s that all about?

We don’t necessarily know that all Hollywood actresses don’t know what they’re talking about.

No, no, I’m saying it has a sort of luvvie quality to it. Is that a word you don’t have here? It’s a rather unfair press name for actors, men as well as women, who take stands on things. Because actors are always [mimes a phony hug and air kiss].

So it’s an empty gesture?

Yes. So, writers as luvvies. I don’t know. I’m being more cynical about this than I really feel. No, it’s quite right that writers should speak out, but it’s so routine now, on every issue. Sometime silence is better.

You have a moment where Perowne is looking at the march and sees the signs reading “Not in Our Name” and there’s a riff on that. What about that slogan bothers you?

I gave him my response to the banner that I loathed the most. It has an icky quality of me-too-ism and consumer self-importance.

To play devil’s advocate, I’ll say that probably those people were saying, “This is a democracy and you say you’re doing this in our name, and we just want to make it clear that we don’t endorse it.”

Well, you don’t agree, but that’s different. If you live in a democracy, even if the president is not the president you voted for, it is in your name. The logic of “Not in Our Name” would be, “I dissent from the democratic principle.” Like it or not, the contract you’re in as a democrat is that even if you’re on the losing side, you give your assent. As long as you think the vote is fair — and that, of course, is another matter.

Why does that slogan make you think of consumerism?

You know how a billboard, with 50,000 cars going by, will say, “The perfume for you” or something like that? What is the grammatical nature of that “you”? It carries a quality of the lonely crowd. It’s sad. You’re supposed to be heartened by the sense that you’re important to the corporation because you’re a consumer. So you’re fussy and picky and you like this bit of government and you hate that bit. You have Diet Coke and you have Triple Mac. But that’s not the deal. You’ve got a government you loathe, and that’s your perfect right, to loathe it and protest it, absolutely. You can’t opt out. You’re in the social contract.

It’s a tricky distinction.

And I’m not sure how far I’m prepared to defend Henry Perowne on this. We’ve got — and I know you’ve got this here — public outpourings of grief about the deaths of people no one’s met. We call it the “damp teddy syndrome.” A little girl is abducted by some madman and it’s all over the tabloids: Will she be found? Within days there are giant mounds of teddy bears. Spilling out onto the pavement, two tons of teddies. It rains, the teddies are there, soaked. People are in a sort of hatefest about the pedophile, they’re sobbing. But it’s not their child, they’ve never met this child, but there’s a great storm of public emotion.

It’s a lot like the way people have ranted and wept on and on about Terri Schiavo, calling her “Terri,” when they don’t know her and have never even seen her in person. It a kind of artificial intimacy

We’ve come to live in this age of confusion between public and private emotions. People feel they know this person. And you’re entitled to sob even though it’s not your life. Then there come the silences. Will there be a two-minute silence for Terri and will you dare to walk across this hotel lobby when everyone else is tearfully standing erect? Are you going to wear a yellow ribbon for Terri? We’ve entered this absurd world.

Yet Perowne does partake of that world. Because his personal life is so content, he becomes very caught up in world events. Yet at one point he asks what good it really does for him to lie around on the sofa all day Sunday reading newspapers and opinion pieces. He feels like he’s participating but he’s really just reading the paper.

Yes, it’s a feeling that I’ve had sometimes, a sense that I’m actually involved. I’m lying there for hours in drifts of newspapers. It’s almost as if I’m chief of staff with a head full of gunships and alliances. Then I realize that I’m just another punter buying a newspaper and my head is filled with other people’s thoughts.